Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Birmingham, Alabama

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

“There is absolutely nothing to the report from Montgomery that there is Spanish influenza in Birmingham or Jefferson County. There are some acute cases of old-fashioned influenza or la grippe.” Thus spoke Dr. J. D. Dowling, Health Officer for Birmingham, Alabama and surrounding Jefferson County, on October 4, 1918.1 In fact, several dozen cases of influenza had been reported to the department of health since the last days of September. Health Officer Dowling dismissed them as severe colds.2

A few days later, however, after reports indicated up to 500 cases of influenza and several deaths, Health Officer Dowling could no longer dismiss the seriousness of the growing problem. Although he still did not believe that all these cases were actually instances of influenza, he at least issued a long statement to the public on the dangers of disease and methods of controlling its transmission. He recommended that people self-limit their exposure to large crowds of people, especially in confined spaces, but did not yet move to close public places.3

The Birmingham Board of Health decided it could no longer afford to wait. On October 7 it recommended that all places of public assembly be closed. The Boards of Education of Birmingham and Jefferson County responded by immediately closing schools for the next two weeks. Meanwhile, the Board of Health prepared a general closure order, which it presented to the Birmingham City Commission for consideration. On October 8, the Commission passed the resolution, thereby ordering closed all churches, Sunday schools, movie houses and theaters, poolrooms, sideshows, and street fairs and carnivals–including the large state fair already underway–and barring public meetings.4 Circuit court judges decided to adjourn their courts for at least two weeks to help prevent the spread of influenza, as did the criminal and civil divisions of the municipal courts. Finally, the Birmingham board of revenue granted Health Officer Dowling full authority to use city funds to fight the epidemic, including isolating in hospitals all cases that could not be treated effectively at their homes.5 Because existing Birmingham hospitals were already at full capacity, Central High School and Colored Industrial High School were converted to emergency hospitals for white and African American patients, respectively.6 After a slow start, Birmingham had finally risen to meet the crisis.

The move came none too soon. Soon, hundreds of new cases were being reported daily, and the daily death toll rose to as high as 31 on a single day (October 18).7 On October 17, the Board of Education voted to keep schools closed for at least another week. The next day, the City Commission extended the general closure order–due to expire on Monday, October 21–for two additional weeks. Over 7,100 cases had been reported thus far in Birmingham, with another 2,100 cases in surrounding Jefferson County.8

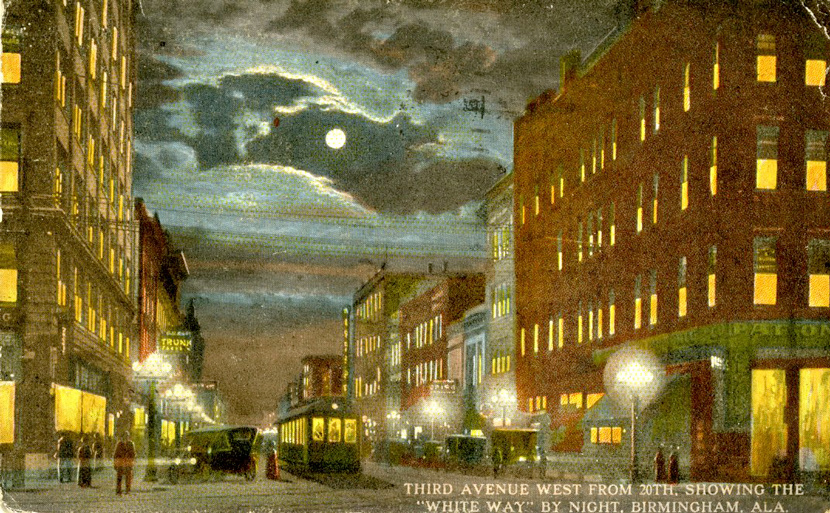

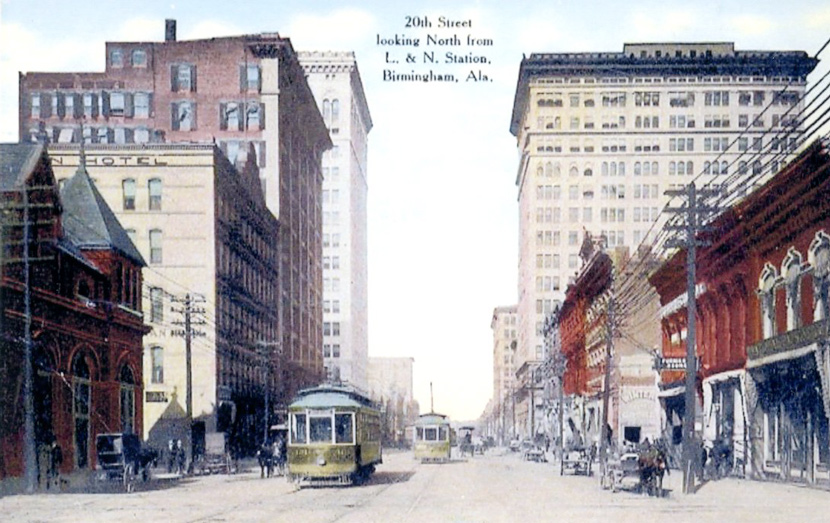

Over the course of the next two weeks, the number of new influenza cases being reported declined drastically. The improvement was reflected in the city’s hospitals: patients at the high school emergency hospitals were being moved to Hillman Hospital. Everyday life in Birmingham was also slowly returning to normal, despite the closure order still in effect. Residents once again began flocking to the downtown-shopping district. In fact, some merchants reported thirty-five percent sales increases over the previous week. An Age-Herald reporter counted four hundred pedestrians passing the Trianon Theater on 2nd Avenue North in a five-minute period.9 The renewed hustle-and-bustle of downtown was welcome news to area business owners.

Even more welcome news was the October 30 decision by the City Commission to lift Birmingham’s closure order, effective the next day.10 Theater and other affected business owners were thrilled. Even merchants, who had remained open during the epidemic, were happy with the news, realizing that it was an official signal to city residents that the danger from the epidemic was essentially over and that they could return to their old buying habits. Theaters had lost an estimated $90,000 during the closure period, and city stores an estimated $160,000 due to the general shopping slump caused by the epidemic. As the Birmingham News put it, undertakers seemed to be the only group to profit during the epidemic.11

Birmingham schools reopened on Monday, November 4. In the rest of Jefferson County, the decision to reopen schools was left to individual communities under the advice of local physicians. As a result, a dozen schools remained closed in areas of the county where the epidemic had not yet run its course.12

In the days after the peace celebrations of November 11, Birmingham experienced an uptick in influenza cases once again. Health Officer Dowling was concerned but not overly alarmed, telling residents that these new cases were generally milder and that they should not worry. Nevertheless, numbers indicated that Birmingham was indeed in the midst of another serious influenza spike. Within days, new case reports went from a trickle of four or five a day to 115 on November 19 alone. Along with these new cases circulated rumors that Dowling and other city officials were attempting to hide from the public the true number of cases, and that the real situation was much more serious. Dowling responded that the Board of Health was releasing the most accurate case numbers it had, and absolutely was not trying to deceive the public.13

As November rolled into December, the number of new cases reported daily had not declined significantly. Dowling urged citizens to wear gauze masks, stating that they were “the most practical and efficient general method at our command to limit the spread of influenza.” To encourage the general public to don masks, members of the police force began wearing them as they walked their beats.14

The Board of Health, along with members of the School Board, the City Commission, and city and county physicians, met to decide whether or not to close schools once again. The group decided that a large portion of the new cases being reported were not actually influenza, but were other illnesses such as severe colds being diagnosed too quickly as influenza by overworked physicians. As a result, the Board of Health opted to keep schools open despite the reported high absentee rates, which it attributed mostly to fearful parents and not to actual cases of illness. Additionally, several involved in the decision felt that children would not only be safer in schools where they could be monitored, but that closing the schools for a second time would lead to many students getting jobs and not returning to the classroom for their studies. Health Officer Dowling argued that a second school closure was not necessary given the milder second peak the city was experiencing. Chicago, he told his colleagues, had not closed its schools at all and had fared well through its epidemic. Dowling told parents to keep their children at home if they showed signs of illness, and instructed teachers to send home any student showing influenza symptoms. A group of local physicians disagreed with the decision, and in a signed statement advised parents to keep all children at home for their safety.15

By this time, however, the number of new cases appearing daily had started to decline once again, and thus the debate over a second school closure had become largely academic. Birmingham’s epidemic was slowly drawing to an end. As the New Year approached, the number of new cases reported daily dropped to a few dozen. Dowling still urged the use of masks and recommended that people avoid crowds and beware of people sneezing or coughing, but he otherwise felt confident that Birmingham residents could go about their daily lives with far reduced risk of contracting influenza.

The city experienced a third spike in cases and deaths in January 1919, albeit one much less severe than that which had hit in the fall. Health officials expected as much, and, realizing that the public was growing tired of news of influenza and discussions of public health measures, decided to let the tail end of the epidemic run its course with no further interventions. Even the city’s two major newspapers, the Age-Herald and the News, stopped reporting on the disease except for sporadic short articles on general health matters. All of Birmingham, it seemed, had grown weary of influenza.

Notes

1 “No Spanish Influenza Here; ‘Cooties’ Attack,” Birmingham News, 4 Oct. 1918, 4.

2 “Twenty Cases of Influenza in Birmingham,” Birmingham News, 29 Sept. 1918, 1; “Grip Is Reported Prevalent Here,” Birmingham News, 1 Oct. 1918, 11.

3 “Influenza Causes Deaths Here; Big Closing Possible,” Birmingham News, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

4 “Influenza Causes Board to Declare Fortnight Holiday,” Birmingham News, 7 Oct. 1918, 1; “Fair, Church and Theaters Ordered Shut Immediately,” Birmingham News, 8 Oct. 1918, 1; “City Commission Adopts Resolution; Health Committee Closing Theaters, Fair, Schools, and Lodges,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 9 Oct. 1918, 5.

5 “Influenza Cases to be Massed, Is Latest Proposal,” Birmingham News, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

6 “Death Claims 10 More Influenza Victims in City,” Birmingham News, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 “Health Officer’s Report,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 19 Oct. 1918, 5.

8 “Closing Order is Extended for One More Week More,” Birmingham News, 17 Oct. 1918, 1; “Closing Mandate Is Extended Here until November 4,” Birmingham News, 18 Oct. 1918, 1.

9 “Epidemic Reaches Its Height, Is General Opinion,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 27 Oct. 1918, 10.

10 “City Commission Will Lift the Ban on All Gatherings at 12pm Tonight,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 30 Oct. 1918, 5.

11 “Influenza Cost City More than Half a Million,” Birmingham News, 31 Oct. 1918, 1.

12 “Several County Schools Fail to Open on Account of Influenza,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 5 Nov. 1918, 5.

13 “Anxious Rumors about Recurrence of Influenza Not Sustained by Facts,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 19 Nov. 1918, 5; “Epidemic on the Decline, Says Dr. Dowling,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 24 Nov. 1918, 5.

14 “Mask Precautions Advised for City,” Birmingham News, 6 Dec. 1918, 7; “Health Meeting is Held and Everyone Wears Gauze Masks,” Birmingham News, 6 Dec. 1918, 8.

15 “Doctors Advise Parents to Keep Children out of School,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 6 Dec. 1918, 5; “Handling of Influenza Situation,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 9 Dec. 1918, 5; “Dr. Dowling Makes Statement on the Health Situation,” Birmingham Age-Herald, 12 Dec. 1918, 5.