Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Cleveland, Ohio

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

On September 22, the people of Cleveland received their first official warning of the impending influenza epidemic from City Health Commissioner Dr. Harry L. Rockwood. United States Army Surgeon General William Gorgas had notified Rockwood of the disease’s spread and the likelihood of it soon arriving in Cleveland.1 Despite the warning, Cleveland was slow to act. It was not until October 4 that City Director of Public Welfare Lamar T. Beman directed Rockwood to undertake a survey of local influenza conditions and to draft a citywide plan of action for precautionary measures against the disease.2

Health Commissioner Rockwood’s plan called for the isolation of those with symptoms of influenza in a contagious disease ward at City Hospital. Employers were asked to instruct sick workers to take time off of work and rest until the symptoms disappeared. Rockwood acknowledged that this was a drastic measure, especially in critical war industries, but argued that it was necessary and would prevent even more time being lost later during an epidemic. Similarly, schools were asked to inspect and monitor students and to send children with symptoms to their homes for rest. Daily reports of all students excused from school were to be made to the Health Department so that their families could be watched as well. The Cleveland Railway Company ordered its motormen to assist in the arrest of all passengers found spitting on their streetcars. A special advisory board was created to help Rockwood. These measures, along with a public education campaign on how to prevent and treat influenza, were Cleveland’s first plan of attack.3

By the end of the first week of October, the situation in Cleveland had grown serious. On October 7, Rockwood announced that the city likely had approximately 500 cases. Only two days earlier, Rockwood had stated that Cleveland’s epidemic was not alarming. Now he was not so sure. To help control the spread of influenza in the city and throughout the greater Cleveland area, the advisory board met with officials from nearby communities. These officials agreed to cooperate with Rockwood to the fullest extent. The advisory board also released instructions to residents not to go to work if they felt sick: “Don’t think that by doing so you are helping the country in its war efforts. You may have influenza and spread the disease and thus deprive the nation of many men’s work. It is therefore your patriotic duty to stay at home if you feel indisposed.” Proprietors of business where the public might assemble as well as clergy were asked to bar people with cold symptoms, and movie house owners were asked to show slides on influenza prevention.4

The next day’s new case reports greatly worried Health Commissioner Rockwood, and on the morning of October 9 he met with Acting Mayor W. S. FitzGerald and Director of Public Welfare Lamar T. Beman to recommend suspending all public gatherings and to close all places of public assembly. Rockwood initially hoped to check the disease through voluntary action. Now he believed, as he told reporters, “more radical steps are needed.” The next day, October 10, Mayor Harry Davis announced the decision to close all theaters, movie houses, dance halls, night schools, churches, and Sunday schools across Cleveland effective Monday, October 14. Saloons, poolrooms, and cabarets were not included in the order because officials believed that it was only necessary to close places where large crowds tended to congregate. The initial plan was to close movie houses and theaters after their Saturday shows on October 12. After protests from owners, however, Rockwood agreed to give them extra time to make arrangements for their closing. As for schools, Rockwood believed students could be better monitored in classrooms than at home.5

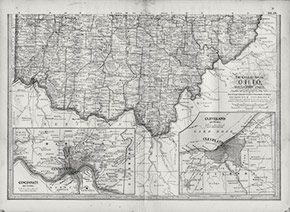

At the same time, state officials in Columbus had determined that the epidemic had grown serious enough to warrant the closure of places of public gathering across Ohio. On October 10, the Ohio Health Department issued a notice to all communities, strongly recommending that they issue a local closure order and gathering ban. The state order gave final authority on the matter to local health departments, however, and Cleveland officials decided to continue with their initial closure order, allowing saloons and similar places of business to operate for the time being.6 Meeting with Health Commissioner Rockwood, school officials devised an elaborate plan: schools would remain open so long as their absentee rates did not climb to twenty percent of enrollment, and would be closed after that point. If the overall absentee rate for all schools combined reached ten percent of total enrollment, then the entire Cleveland school system would shut its doors until the epidemic had passed.7

By October 14, the first day of the gathering ban, school absences were high enough for officials to consider closing all of Cleveland’s schools. Health Commissioner Rockwood admitted that such a move would be a drastic step, but stated, “it would be a calamity to allow them to remain open if a considerable number of the pupils are affected.” Rockwood estimated that there were at least 300 children with influenza in the city. Meeting with school officials later that day, Rockwood and the superintendents decided that it was indeed time to close the schools, effective Tuesday, October 15. Children were to report to their classrooms as usual in the morning, where attendance would be taken before they were dismissed. School nurses and doctors were to make home visits to check on students who did not show for class. Teachers were expected to remain in the city during the closure so that schools could re-open quickly as soon as the danger had passed. They were to receive regular pay during the closure period. Parents were told to keep their children in their own backyards, allowing them to get plenty of fresh air and exercise but preventing them from mingling with other children.8

Children may have been granted an unexpected vacation, but teachers were not. The next day, the city’s 3,500 teachers were told to report to their schools to assist nurses investigating cases from the previous day’s 12,500 absences.9 As it turned out, the vast majority of the absent students were truants who, hearing that schools would be closed if absences were high enough, tried to force the issue by remaining away from school. Only a few hundred actual cases were found during the canvas. Discovering their “plot,” school authorities announced that schools would reopen on Monday, October 21.1 When several hundred more students developed influenza in the course of the next several days, however, school officials decided to keep the classrooms closed as originally announced.11

While the city’s schoolchildren were crafty, some residents were outright brazen. Several churches appealed to Health Commissioner Rockwood to be allowed to hold services provided they were kept to an hour; Rockwood denied their request. Two Jewish synagogues decided to ignore the order anyway and to hold indoor services away from their usual temples. Police arrested nine of the men, who pleaded that they were simply worshipping, not holding regular religious service. At a cigar store card game broken up by police, players insisted they were not gambling. Police did not care: the gambling was not the problem, the public gathering was. In another case, a candy shop owner and six others were arrested for allowing people to congregate in the store. Cleveland police took the public gathering ban very seriously.12

As Cleveland police did their job, Health Commissioner Rockwood prepared the city for the brunt of what he expected would soon arrive. He asked the mayor’s advisory war board for a whopping $105,000 in order to equip an emergency influenza hospital, arguing that the epidemic posed a threat to war industries in the Cleveland area. Though only 350 hospital beds were currently available, Rockwood estimated that 1,000 would be needed within the next few days for incoming influenza patients.13 The Red Cross set aside $20,000 to help Rockwood obtain adequate facilities in the suburbs, with the intimation that more funds would be made available if necessary. Rockwood welcomed the money, as he estimated it would cost $122,000 to equip 1,000 beds and to pay for 100 nurses employed for ten weeks.14

By Monday, October 21, Health Commissioner Rockwood estimated that there were 1,000 influenza patients being treated in Cleveland hospitals, with a new case rate that would very quickly outpace the ability for patients to be properly cared for in city facilities. Rockwood arranged to have the Cleveland Normal School at University Circle converted into a 100-bed emergency hospital, and asked all private hospitals to use their free beds for influenza patients. “Cleveland hospitals, as a whole, have been doing good work,” he told reporters, “yet we have not had the proper support from some. These institutions frequently call on the city for financial help and they should respond now.” The Liberty Loan committee quickly offered use of its headquarters, with room for 20 beds, to serve as an emergency hospital annex to nearby Grace Hospital. Rockwood expressed his gratitude, but added that the city desperately needed other similar offers.15

Within just a few days, the epidemic situation in Cleveland had grown significantly worse. Completing the survey and report of the city’s school children, School Medical Director Dr. L. W. Childs announced that at least 1,269 were sick with influenza. Across Cleveland, some 7,323 cases had been reported since the start of the epidemic, with 776 of these being added to the list on October 22 alone. Rockwood, desperate to halt the spread of the disease, added a series of new regulations to the closure order and gathering ban. Business hours in the downtown district were restricted and staggered. Offices were to close by 4:30 pm, wholesale houses by 4:45 pm, small retail shops by 5:00 pm, department stores by 5:30 pm, grocery and hardware stores by 6:00 pm, and saloons and restaurants by 8:00 pm. Only essential services such as telegraph offices and drug stores could remain open past these restrictions, provided they did not sell tobacco–a concession to cigar shop owners. All open-air gatherings, including political meetings, were prohibited without permission, and none were to be held after sundown. The new closing hours were noted to have been so closely observed that, “not even a cigar could have been purchased last night in the downtown district.” In fact, they may have been too closely followed, as night workers and policemen discovered how difficult it could be to find a bite to eat in the late hours.16

Ministers were not happy with the new situation, however. They complained that saloons were becoming points of congregation since they were allowed to remain open later than other businesses. Health Commissioner Rockwood revised the restrictions and required saloons to close by 6:00 pm, a move that appeased some but left members of the temperance movement upset.17 Unable to use their pulpits to preach their cause, a group of one hundred Cleveland clergy joined together for a house-to-house canvass to gain support for prohibition. They called for the closure of saloons and an end to the “discrimination” of allowing these places of immoral behavior to remain open while churches and theaters were shut tight.18

By the first days of November, the epidemic situation had improved enough for Rockwood to consider lifting the ban. Beginning on November 5, downtown businesses were allowed to remain open until 6:00 pm rather than 4:30 pm. Churches were allowed to hold one service each beginning on Sunday, November 10. Meeting with school officials, Rockwood announced that he would not oppose the reopening of schools in a week or so, provided the epidemic situation did not take a turn for the worse. Some school board officials were not entirely sure, worrying that schools would reopen too soon. Rockwood added that he would lift the rest of the bans at the same time.19

As promised, on the evening of Sunday, November 10, Health Commissioner Rockwood announced the lifting of the closure order and gathering ban effective the next day. Schools would not reopen until Wednesday, November 13 to allow for the continued services of school nurses, teachers, and Catholic sisters volunteering in the fight against influenza. Suburban officials, waiting for Cleveland’s lead, also announced their reopening, including nearly every school outside of the city’s school district.20

Clevelanders were excited to once again head downtown for evening entertainment. Musicians and actors were happy to be employed once again, and owners and proprietors were thrilled to be back in business as theaters, boxing rings, stadiums, and ballparks opened to capacity crowds. The month-long closure had cost proprietors more than $1.25 million combined. Conservative estimates of daily loses ran at $11,000 for theaters, $25,000 for movie houses, $12,000 for bars and saloons, and $2,000 for soda fountains. Hotels had also taken a hard hit, as patrons postponed or cancelled conventions. One assistant manager estimated that his establishment had lost $50,000. The total gross loss for all Cleveland hotels was estimated at $200,000. This amount likely would have been even higher had theatrical companies not been forced to hole-up in Cleveland hotels for much of the duration of the gathering ban. With fewer people traveling downtown for entertainment, the Cleveland Railway Company estimated it had lost approximately $200,000, with the greatest daily losses coming on Sundays.21

Over the course of the next several weeks, Cleveland life slowly returned to normal. Cases among school children were still reported in numbers significant enough to concern health officials, but not so much as to require another shutdown of the city’s schools. Instead, the “unit system” initially used was once again put in place: if absenteeism reached twenty percent in a classroom or a school, those rooms or even entire school buildings would be closed until an investigation could determine how many students were actually ill. By mid-December, twelve city schools had been temporarily shut, but Health Commissioner Rockwood and school officials believed that no general school closure would be necessary.22 Cleveland slogged through the rest of its epidemic with no further closure orders or bans.

Influenza had exacted a heavy toll on Cleveland. Between late-September and the end of the year, 23,644 residents fell ill with the disease, with nearly 1,600 developing pneumonia. Over 3,600 people died of either influenza or pneumonia that autumn. An additional 800 deaths occurred in January and February 1919. In those five months, 3.5% of the city’s population came down with influenza or pneumonia; of those that caught the dreaded disease, 16% passed away.23 The result was a total excess death rate of 474 per 100,000, the highest in Ohio, and worse than either New York City or Chicago.

Notes

1 “Warns to Watch for Spanish Flu,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 22 Sept. 1918, 1.

2 “Spanish Flu to Meet with Fight by City,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 4 Oct. 1918, 1.

3 “Isolation Will Be Used in Flu Fight,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 5 Oct. 1918, 1; “Wars on Spitting to Help Avoid Flu,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

4 “Open Campaign to Free City of Flu,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

5 “Ban on Meetings Asked in Flu War,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

6 The Ohio state department of health did not issued a mandatory state-wide closure order, believing that local communities should be left free to adapt the general closure order recommendations to their needs. See “Controlling the Influenza Epidemic in Ohio,” The Ohio Public Health Journal 9 (Nov. 1918), 453-456.

7 “Case Goes Under Quarantine,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 12 Oct. 1918, 1.

8 “Confer Today on City School Ban,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 14 Oct. 1918, 6, “All City Schools Shut After Today,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 15 Oct. 1918, 1, “School Head Urges Children Be Kept in Own Back Yard,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 15 Oct. 1918, 9.

9 “3,500 Teachers to Combat Influenza,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 16 Oct. 1918, 7.

10 “See Little Flu, Lots of Hookey,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 17 Oct. 1918, 1, “300 Get Flu Care Soon in Hospitals,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 17 Oct. 1918, 10.

11 “Influenza Deaths Doubled for Day,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 22 Oct. 1918, 5.

12 “Flu Closes City Churches Today, Cleveland Plain Dealer, 20 Oct. 1918, 2A; “Influenza No Excuse,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 21 Oct. 1918, 7.

13 “Wants $105,000 for Flu Hospital,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 16 Oct. 1918, 7.

14 “300 Get Flu Care Soon in Hospitals,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 17 Oct. 1918, 10.

15 “29 More Die of Influenza in Day,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 21 Oct. 1918, 7, “Influenza Deaths Doubled for Day,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 22 Oct. 1918, 5.

16 “Ban Is Extended as Flu Spreads,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 23 Oct. 1918, 1, “Catholic Sisters Take Up Flu Fight,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 24 Oct. 1918, 8.

17 “Closes Bars at 6, New Flu Mandate,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 25 Oct. 1918, 8, and “Flu Fighters to Serve Free Food,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 26 Oct. 1918, 8.

18 “Drys to Cite Flu Ban Differences,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 27 Oct. 1918, 8A.

19 “Flu Orders Start Moderating Today,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 5 Nov. 1918, 8.

20 “Flu Lid is Lifted Sunday Midnight,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 10 Nov. 1918, 1B.

21 “Epidemic Brings Big Money Loss,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 11 Nov. 1918, 7, “Flu Cut $200,000 from Car Fares,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 21 Nov. 1918, 13.

22 “Rooms in Schools Get Flu Ban Now,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 13 Dec. 1918, 2, “3 More Schools Are Shut by Flu,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 17 Dec. 1918, 2, “Flu Ban Spreads to More Schools,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 18 Dec. 1918, 6.

23 Case and death figures taken from City of Cleveland, Ohio, Division of Health: Statistical Records, Years 1916-1924 (Cleveland, 1925), 42-44.