Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Fall River, Massachusetts

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

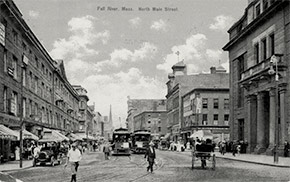

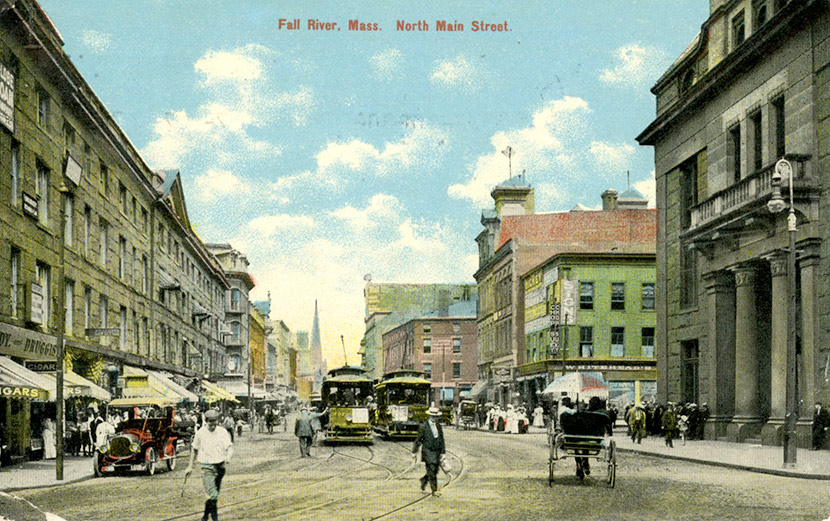

In a sense, Fall River was caught between the anvil and the stone in the fall of 1918. Boston – epicenter of the influenza epidemic – was just 50 miles away, while Newport, Rhode Island and its naval stations was even closer, a scant 22 miles. Personnel from military installations near both cities regularly paid visits to Fall River, and it was through such visits that influenza was brought to the city: of the first five cases reported to the Fall River Board of Health on September 16, two were soldiers on leave from Camp Devens and two were from the Boston Navy Yard.1 City Health Agent Samuel Morriss and the Board of Health sprang to action. Morriss asked physicians caring for these patients to keep them well isolated so as to prevent the spread of the disease. The Board of Health instructed school inspectors to begin examining children for signs of illness, and asked police to keep residents from spitting on the streets. A prescient physician who correctly assumed that the Board of Health would be interested to know that influenza was now within Fall River city limits had reported the first crop of cases. On the suggestion of member Richard Borden, the Board therefore unanimously voted to make influenza a mandatory reportable disease. Lastly, the Board prepared a public service announcement to be printed in the city’s newspapers, advising the public on how to prevent and treat influenza.2 The next day, physicians reported seven more cases of influenza.3 Fall River’s epidemic was about to get underway, but fortunately so were its officials.

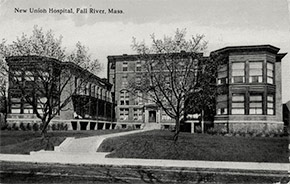

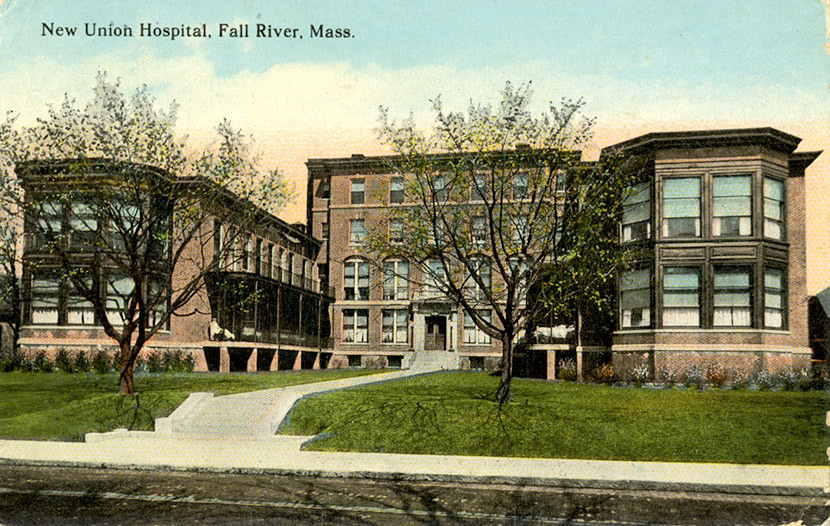

In a little over a week there were 602 reported cases of influenza in Fall River and 17 deaths due to the disease.4 The sudden spike alarmed members of the Board of Health, who hurriedly met on the afternoon of September 26 to review the situation. Massachusetts Department of Health Director Dr. Eugene R. Kelly advised against closure orders, but other state officials – namely Governor Samuel McCall – disagreed.5 With over 50,000 reported influenza cases circulating in Massachusetts, the spread of the epidemic to at least half the country, and the likelihood of the state of affairs in Fall River growing far worse before it got better, Morriss and his colleagues decided to side with McCall. The Board ordered closed all public and private schools, movie houses, and theaters, banned assemblies, lectures, and other public gatherings, and requested that clergy close their churches and halt Sunday schools until the threat of the epidemic had passed. Most subsequently did. Restaurants and other places that served food or drinks were warned to keep their premises and their dishes and utensils clean.6 The next day, Fall River Mayor James H. Kay issued a proclamation, declaring a state of emergency in the city and endorsing the actions of the Board of Health, which now included large wakes and public funerals on the list of prohibited gatherings. The school committee met and ordered schools closed, although, given that the Board of Health had full authority in the matter, this action was superfluous.7 Authorities had already begun barring visitors at hospitals in an attempt to contain the epidemic, and had prohibited new admissions because of the lack of nurses, several of whom had already fallen ill.8 Fortunately, the Home Nursing department of the local chapter of the Red Cross was able to recruit a half-dozen nurses’ aides to work at City Hospital.9

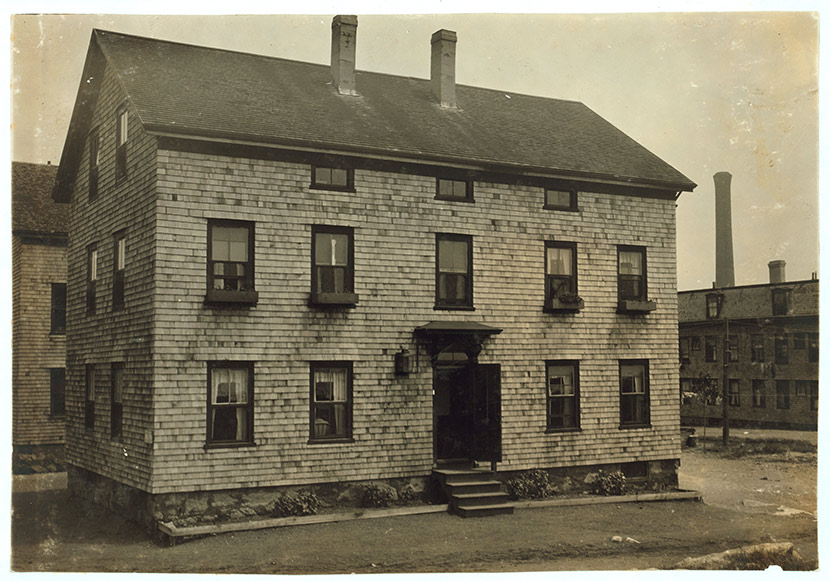

Other organizations joined in the cause. On September 30, Mayor Kay convened a meeting of health and hospital officials and representatives of Fall River’s various charities and relief societies. There, the group discussed the growing epidemic and outlined a plan of action to handle cases and to ameliorate the suffering of the ill and their families. The Sisters of Mercy of Mount St. Mary’s convent offered their nursing services to the afflicted of the city, which included the wife of Board of Health Secretary Louis J. Cahill.1 The Red Cross took on the role of clearinghouse for those trying to obtain a physician, and announced it would assist those who could not afford or locate one. To help those too sick to cook for themselves, it opened canteens to prepare and distribute meals. Volunteers used the kitchens of the city’s now-closed schools to cook meals, turning out several hundred dinners per day.11 The Women’s Union made soups and custards to help fortify the ill.12 The volunteers at the King Philip Settlement House at 334 Tuttle Street provided meals for stricken South End families. The rector of the St. Mary’s Cathedral offered the use of the church’s Bishop Stang Day Nursery for use as an emergency hospital, as did clergy at the St. Patrick’s Day Nursery. The District Nursing Association recruited nurses and physicians to serve in the new temporary hospitals.13 Some teachers lent a hand, volunteering as nurses’ aides.14 Morriss worked as hard as anyone, keeping the department of health open from 9:00 am until 10:00 pm to handle the workload, and answering calls during off hours at his home.15 Working through the Board of Health, the various city agencies and relief organizations did their best to help Fall River get through the epidemic.

Not all groups were as eager to join the cause. In particular, saloon owners and liquor dealers grew upset when the closure order came to include their establishments. Initially, Fall River’s closure order did not extend to saloons, a move that angered some. Most upset were leaders of the temperance movement. In a scathing attack on the saloons, James E. Cassidy, Vicar General of the Diocese of Fall River, blasted city officials for not closing saloons. “Why are they [saloons] not ordered closed?” he wrote in an open letter printed in the city’s newspapers. “Are not the motley gatherings of the ‘great unwashed’ assembling in these unclean places, particularly on Friday and Saturday nights, a thousand times greater a threat than the congregations of our churches?... Is German brewery power supreme in city and State House?”16 A few days later, after state authorities requested that soda fountains close, the Board of Health met and recommended that the sale of beverages in saloons, drug stores, and soda fountains be halted. It was, in fact, an extension of the existing closure order, as the Board made it explicitly clear that a formal order would be issued if proprietors failed to comply with the request.17 Unhappy saloon owners complained directly to Mayor Kay, who refused to budge on the issue.18 A few days later, the Board of Health voted to allow wholesaler liquor dealers to fill small orders for home delivery, a move that did not appease angry saloon owners.19

Soda, ice cream shop, and drug store owners were in no better mood than were their counterparts in the saloon business. At first, some had attempted to circumvent the “request” by simply serving beverages and ice cream in paper cups rather than glasses, believing that sanitation was the primary concern of the Board of Health. It was not. The Board was most troubled by the propensity for such establishments to draw crowds. When warned to cease, several complained to Morriss, who relayed to the Board of Health the information that the proprietors felt put out about the situation. Borden replied that people needed to put up with some hardships given the nature of the crisis. When Morriss responded that Boston still allowed shops to serve beverages, Borden cut him off: “I don’t care what they are doing in Boston and other places. We are handling the situation for this city.” He then instructed the secretary to strike “recommends” and replace it with “orders” in the language of the Board’s previous edict.20

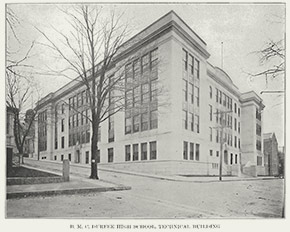

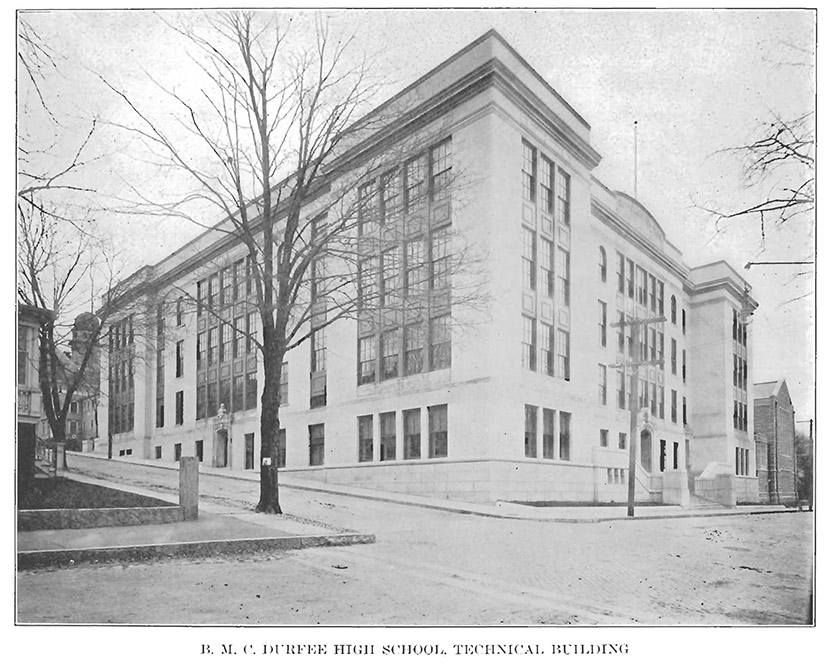

Meanwhile, onward the epidemic marched. The first weekend of October saw an additional 1,914 influenza cases, bringing the total since the start of the crisis to over 6,600. The Red Cross announced that its volunteers would work 24-hours a day, seven days a week to handle the increasing number of calls for help. Boy Scouts volunteered to run errands and to distribute 15,000 pamphlets printed in Portuguese and Polish to workers as they left their factories and mills, advising them on influenza precautions and care. St. Anne’s Hospital opened a ward to care for Fall River’s influenza victims, and authorities opened the city’s Technical High School as an additional 75-bed emergency hospital. Ten doctors from the United States Public Health Service and a dozen nurses from out-of-town arrived to lend their aid, as did 12 members of the State Guard to serve as ambulance drivers and hospital orderlies. The owner of the Hotel Mellen and the head of the girls’ industrial school at the Deaconess Home offered their buildings as emergency hospitals as well, but for the time being the situation, precarious as it was, did not demand additional hospital space.21 Moreover, the city would have been hard-pressed to staff them.

It was already becoming difficult to deal with the number of deaths. Undertakers were working as fast as they could to prepare bodies for burial, but they were still hard-pressed to keep up with the death rate. At the St. John’s Day Nursery emergency hospital the body of an influenza victim lay for a night and day, awaiting the overworked undertaker to arrive. Finally, an alternate undertaker had to be contacted to come retrieve the body because the first one was simply too busy. Morriss and Kay conferred about the problem and decided that a temporary morgue would be established at the old police department to temporarily keep bodies until undertakers could prepare them for interment.22 Even still, bodies piled up. At Notre Dame Cemetery, several dozen bodies accumulated in the vault and shed while the church’s dozen gravediggers worked to prepare graves.23 Adding to undertakers’ vexations, the Board of Health placed on them the onus of ensuring that public funerals did not occur, requiring them to halt the funeral if anyone other than immediate family were present.24 According to authorities, funerals amongst Fall River’s large immigrant population were particularly problematic because of the large turnout they tended to bring. A rather unsympathetic newspaper reporter for the Evening Herald complained of the difficulty in making “these people understand the situation and it requires constant warning to restrict this infringement of rules and regulations of the Health department.”25

By mid-October it appeared as if the crest of Fall River’s epidemic had passed. The number of new cases being reported each day had started to dwindle, and the situation in the city’s hospitals began to improve.26 Outside experts following Fall River’s epidemic concurred. In a special conference between the United States Public Health Service, Massachusetts health officials, Army medical officers, and city health officials, Morriss and his colleagues were praised for their good work in bringing about the end of the epidemic.27 Residents were undoubtedly happy as well, but were now growing restless with their lack of entertainment outlets. Many began pestering Morriss with inquiries as to when the closure order and gathering ban might be lifted. The beleaguered Health Agent responded that, with the exception of churches, the Board of Health would give no consideration to the matter until its next meeting, scheduled for the evening of Monday, October 21.28 Protestant churches elected to remain closed for the time being, but Catholic services resumed on Sunday, October 20, albeit only with low mass.29 Fall River would have to wait at least one more week to enjoy itself.

Fifty-four new cases of influenza were reported on October 21, prompting the Board of Health to defer a decision whether or not to remove the closure order. Weighing on the members were the opinions of the Chamber of Commerce, the Cotton Manufacturers Association, and the Board of Hospitals, all of which urged keeping the orders in place for an additional week to ensure that the epidemic was truly coming to an end. Several of the Board members were of the same opinion, although Borden believed that the epidemic would run its course in its own time, regardless of the interventions of authorities. He recommended that the Board meet the next afternoon and assess the situation then, adding that the issue of when to reopen schools should be left to education officials.30

When the Board met on the afternoon of Wednesday, October 23, the members had all altered their opinions slightly. No longer did anyone advocate for waiting an additional week. Instead, they believed that peak of the epidemic had passed and that the disease had largely run its course. “I don’t believe we will gain anything by continuing the restrictions,” remarked City Physician Sandler. Another member stated that small numbers of cases likely would continue throughout the winter, implying that continuing the closure order and gathering ban would have no effect on the disease at this point. The others agreed. Beginning at midnight that evening, all restrictions save the closure of schools would be removed.31 School officials had previously weighed in that their buildings would not be ready to reopen for class until Monday, October 28 at the earliest. Several days later, the school board met and made that date official. The three-week impromptu break would soon come to an end for the city’s schoolchildren.32 In the meantime, Fall River could return to business as usual.

In most cities, the lifting of closure orders resulted in a great rush to the theaters, movie houses, saloons, and shopping districts as people sought to shake off the boredom and put their minds towards something else besides talk of the dreadful epidemic. In Fall River, however, theaters reported low attendance and proprietors of saloons and drug store soda counters said business was much less brisk than anticipated. It seemed that, despite the clamor to have the restrictions removed, residents were not keen on taking any chances that the epidemic was not truly over.33

As the number of new influenza cases waned, Fall River’s numerous emergency hospitals closed their doors and returned to their normal function. In late-October, the Superintendent of Hospitals tasked a group of city workers with repainting and renovating the two Catholic day nurseries.34 Students at Technical High School – who for the time being had been attending class at adjacent Durfee High (which then stood at 289 Rock Street and now serves as a state courthouse) while their building was being used to care for influenza patients – returned to their usual classrooms on Monday, November 4 after that building had been cleaned and fumigated.35 New cases dwindled but still continued, and some of these resulted in death, but for the most part Fall River returned to its normal state of affairs.

With the crisis over, the city turned its attention to the epidemic’s aftermath. In early-November, city officials met with representatives of Fall River’s various social and charitable agencies to discuss what steps needed to be taken now that the end of the epidemic had come. This Epidemic Follow-Up Committee, as it was known, determined that, for the most part, Fall River was well on its way to recovery. A convalescent hospital, once thought necessary, was not needed. The Community Welfare Office found that majority of homes affected by influenza had returned to normal and needed no nursing after-care. What was needed was aid for families that had dealt with influenza, especially in cases where the primary wage earner had been ill for a length of time. Many of those families had been brought to destitution by the loss of income, and had desperate need for a few weeks’ worth of clothing and milk for the children and coal to keep the home warm. The District Nursing Association would take on the task of working with dealers to distribute milk to needy families, while the Red Cross canteen service would continue to operate until the most pressing need in the remaining families was addressed. After that, service organizations could return to their normal day-to-day operations.36

There was a brief and minor spike in new cases in mid- to late-November, which Morriss attributed to the Armistice Day celebrations and a spate of inclement weather. By mid-December, however, with the daily case tallies hovering around two dozen and an increase in student absences, Morriss began to grow concerned that the epidemic might be making a comeback. To prevent that from happening, the Board of Health briefly considered implementing modified restrictions such as placarding of houses with influenza cases. The majority of cases appeared to be milder than those that occurred during the midst of the epidemic, however, and Morriss and the Board believed that physicians mistakenly were reporting bad colds as influenza. Rather than subject residents to onerous placarding and quarantining, the Board instead focused on a thorough examination of each of the city’s schoolchildren by school doctors in the week leading up to the winter recess. Those children found ill with influenza were sent home immediately to rest and recuperate over the holidays. In addition, the usual school Christmas assemblies were cancelled. Adults were simply warned against unnecessary crowding.37 In the end, school doctors found that most of the absences were not due to illness, and the Board took no further action for the time being.38

On New Year’s Eve, as the number of new cases began to creep up slightly, the Board of Health decided to enact a few minor restrictions. Those with an influenza patient in their homes were warned not to entertain guests. Nor were they allowed to borrow books from the library. School medical inspectors were instructed to keep a close eye on students and to send home any sick children immediately; sick children would not be readmitted to school without the written permission of the Board of Health. Lastly, undertakers were once again told to limit funeral attendance to immediate family.39 It was the last of Fall River’s influenza epidemic control measures.

Influenza clung tenaciously to Fall River throughout the rest of the winter, although fortunately it caused only a handful of additional deaths. The overall toll of the epidemic on the city was staggering, however. Between September 16 and the end of 1918, 11,707 cases of influenza were reported to the Fall River Board of Health. Of these cases, 719 died.40 For the period when the disease was considered epidemic – September 16 to October 31 – Fall River experienced 10,624 cases and 629 deaths. These figures are undoubtedly low, however, given that influenza was not a reportable disease until October 4. The total excess death rate for the period through the end of February 1919 was 621 per 100,000, lower than Boston’s 710 but higher than either Cambridge (541) or Providence (574). Among the victims were two of Morriss’s own children; the health agent lost his young daughter to influenza in early October, and his son – a physician in the Medical Reserve Corps – when he contracted influenza after returning home for his sister’s funeral.41 In addition to the lives lost, the epidemic cost Fall River $19,075, not including the cost of disinfecting and renovating the various buildings loaned to the city for use as emergency hospitals or the $1,100 paid by the Red Cross.42

Notes

1 “Spanish Influenza Here,” Fall River Evening News, 16 Sept. 1918, 2.

2 “Must Report All Cases of Influenza,” Fall River Evening News, 17 Sept. 1918, 10. The announcement appeared on September 19. See, “Board of Health Notice to the Public,” Fall River Evening News, 19 Sept. 1918, 2.

3 “Fourteen Influenza Cases,” Fall River Evening News, 18 Sept. 1918, 6.

4 “Board of Health to Fight Epidemic,” Fall River Evening Herald, 26 Sept. 1918, 1.

5 “Epidemic Cripples Hospital Staff,” Fall River Evening Herald, 20 Sept. 1918, 1; “Suggests Theaters and Schools Close,” Fall River Evening News, 25 Sept. 1918, 3.

6 “Board of Health to Fight Epidemic,” Fall River Evening Herald, 26 Sept. 1918, 1.

7 “Mayor Endorses Board of Health,” Fall River Evening Herald, 27 Sept. 1918, 1; “Offer of Nuns’ Services as Nurses,” Fall River Evening News, 28 Sept. 1918, 4; “No Action Needed by School Board,” Fall River Evening Herald, 27 Sept. 1918, 1.

8 “Epidemic Cripples Hospital Staff,” Fall River Evening Herald, 20 Sept. 1918, 1.

9 “Mayor Endorses Board of Health,” Fall River Evening Herald, 27 Sept. 1918, 1.

10 “No abatement in influenza wave,” Fall River Evening Herald, 28 Sept. 1918, 1.

11 “Too Much Visiting of Sick People,” Fall River Evening News, 30 Sept. 1918, 6; “Red Cross is Clearing House During Epidemic,” Fall River Evening Herald, 30 Sept. 1918, 10; “Invalid Foods for Grip Victims,” Fall River Evening News, 2 Oct. 1918, 2; “Another Diet Kitchen Opened,” Fall River Evening News, 3 Oct. 1918, 2.

12 “Epidemic Figures Again Jump Upward,” Fall River Evening Herald, 4 Oct. 1918, 1.

13 “Pool Efforts to Fight Epidemic,” Fall River Evening Herald, 1 Oct. 1918, 1; Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Fall River, 1919), 22-23.

14 “Fall River Calls for 50 More Nurses,” Fall River Evening News, 3 Oct. 1918, 3.

15 Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Fall River, 1919), 25.

16 “Shut the Saloons, Says Mgr. Cassidy,” Fall River Evening News, 28 Sept. 1918, 1.

17 “Recommend that all Saloons Close,” Fall River Evening News, 1 Oct. 1918, 11.

18 “390 Cases Less than Yesterday,” Fall River Evening Herald, 3 Oct. 1918, 1.

19 “Wholesalers May Open Their Places,” Fall River Evening Herald, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

20 “Wholesalers May Open Their Places,” Fall River Evening Herald, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

21 “Red Cross Rooms Open All Night,” Fall River Evening News, 5 Oct. 1918, 8; “Drop in Cases of Influenza,” Fall River Evening News, 5 Oct. 1918, 1;“Little Change in Situation,” Fall River Evening News, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

22 “Situation Looks Very Much Better,” Fall River Evening News, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

23 “Crest of Epidemic is Thought Passed,” Fall River Evening News, 14 Oct. 1918, 1.

24 “Stricter Ban on Public Funerals,” Fall River Evening News, 10 Oct. 1918, 2.

25 “294 Cases and 35 Deaths Reported,” Fall River Evening Herald, 15 Oct. 1918, 1.

26 “47 New Cases and 9 Deaths Reported,” Fall River Evening Herald, 22 Oct. 1918, 1.

27 “Crest of Epidemic is Thought Passed,” Fall River Evening News, 14 Oct. 1918, 1.

28 “Thinks Epidemic is under Control,” Fall River Evening Herald, 16 Oct. 1918, 6.

29 “To Be No Let Up in Restrictions,” Fall River Evening Herald, 17 Oct. 1918, 1;

30 “Health Board May Act Today,” Fall River Evening News, 22 Oct. 1918, 1.

31 “Ban Taken Off on Gatherings, Fall River Evening News, 23 Oct. 1918, 1.

32 “Public Schools Reopen Monday,” Fall River Evening News, 25 Oct. 1918, 1. For the time being, students of Technical High School attended Durfee High while their school was used as an emergency hospital.

33 “Epidemic Still Affects Business,” Fall River Evening Herald, 25 Oct. 1918, 1.

34 “Only 50 Cases and 12 Deaths,” Fall River Evening Herald, 28 Oct. 1918, 1.

35 “Influenza Report: 25 Cases, 4 Deaths,” Fall River Evening News, 30 Oct. 1918, 2.

36 “Early Recuperation from the Epidemic,” Fall River Evening News, 8 Nov. 1918, 5.

37 “Would Prevent New Influenza Outbreak,” Fall River Evening News, 13 Dec. 1918, 6; “Board of Health Advises Care to Avoid Infection,” Fall River Evening Herald, 14 Dec. 1918, 2; “Precautions to Check Influenza,” Fall River Evening News, 17 Dec. 1918, 12; “Places Ban on Xmas Assemblies,” Fall River Evening Herald, 18 Dec. 1918, 1.

38 “No Recurrence of Epidemic Looked For,” Fall River Evening News, 24 Dec. 1918, 10.

39 “Service Brought Influenza Here,” Fall River Evening Herald, 31 Dec. 1918, 1.

40 “New Rules to Guard against Influenza,” Fall River Evening News, 31 Dec. 1918, 1.

41 “907 new cases of influenza in city,” Fall River Evening Herald, 2 Oct. 1918, 1; “Increase in deaths, decrease in cases,” Fall River Evening Herald, 11 Oct. 1918, 1, 8.

42 Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Fall River, 1919), 44, 37.