Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

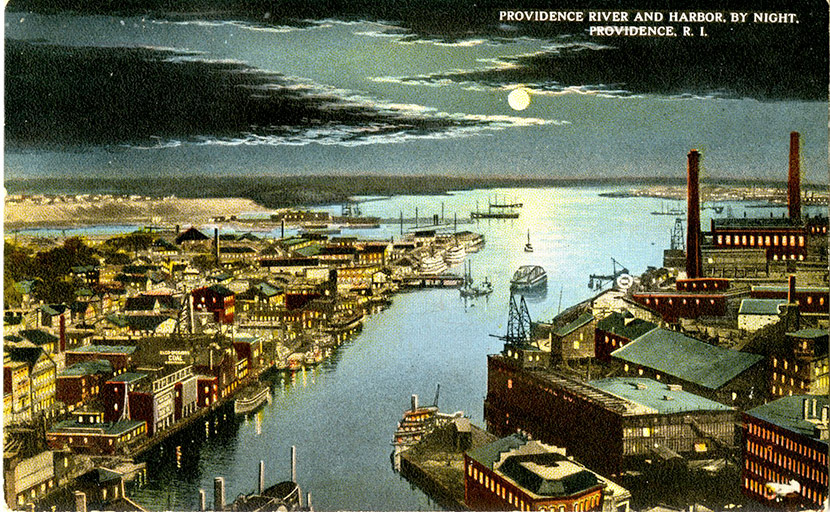

Providence, Rhode Island

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

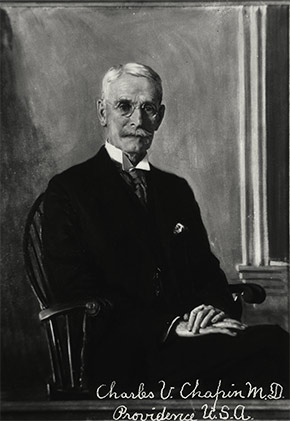

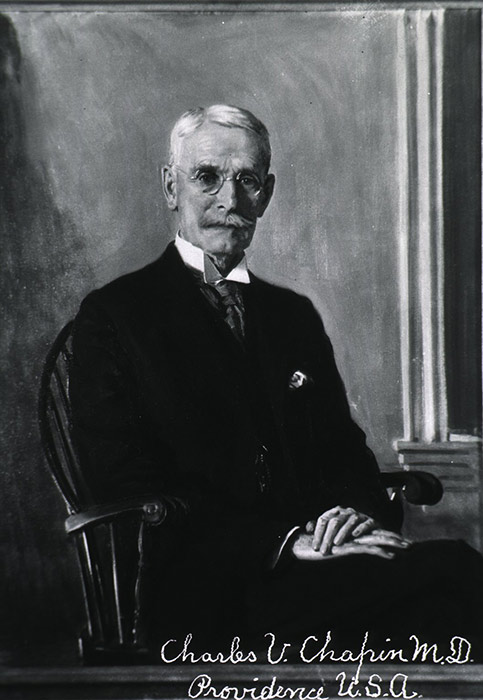

As a northeastern city located near Boston and Camp Devens, the epicenter of the 1918 influenza pandemic in the United States, it came as no surprise to residents and authorities that cases appeared at the city’s doorstep in mid-September 1918. The first local cases were from the Rumford Rifle Range, a small naval facility located only a few miles across the Providence River. Other military stations, including the naval training station and Fort Adams in Newport at the mouth of the Narragansett Bay and the Green Hill Coast Guard station, also reported cases. Many of these cases, and all the cases from the rifle range, were admitted to Providence hospitals, bringing the ill in direct contact with city residents. Soon civilian cases began to develop, and by the last week in September there were well over 100 cases in the city’s hospitals. Undoubtedly many more unreported cases existed in homes across Providence. Superintendent of Health Dr. Charles V. Chapin declared that the influenza situation in the city was not as bad as it was in Boston, only 45 miles to the north, but that it was worsening. This assessment was based solely on observation and on hospital admittances, however, as physicians were not required to report cases.

On the afternoon of September 27, Governor Robert L. Beeckman convened the state Board of Health. After some deliberation, the Board asked Governor Beeckman to issue a proclamation ordering all places of public amusement closed. Superintendent of Health Chapin, along with Providence Mayor Joseph H. Gainer, opposed such a measure, arguing that it would do little good in combating the epidemic, as closing public places would not prevent the disease from spreading via other routes. Instead, Chapin believed, the epidemic should be left to run its course. “The children, if turned out of school, will mingle on the streets. People turned out of churches or other places will mingle just the same all other days of the week, in streetcars, factories or places of business. They will mingle in the stores.” The time for such an order, Chapin stated, was several weeks prior, when it may have had some positive impact.1 After meeting separately with Mayor Gainer, the Secretary of the state Board of Health, representatives of the city theaters and movie houses, and Chapin, Beeckman decided against issuing a closure order for the time being.2

Charles Value Chapin and Providence Public Health

Chapin was no naysayer or medical slouch. After graduating from Brown University in the spring of 1876, he spent a year as an apprentice to a local homeopath, reading medical texts and accompanying the doctor on house calls. In September 1877, he began his formal medical training at New York’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. At the end of the academic year Chapin transferred to Bellevue Medical College, where he met classmate William Gorgas, who would become the Surgeon General of the Army in 1914, and trained under the young pathologist William Henry Welch, who would become the first dean of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893.

After graduating with his medical degree from Bellevue in the late winter of 1879, Chapin spent the next six months as an intern at Bellevue Hospital, where he was able to see and treat first-hand a host of urban diseases. It was during his time at Bellevue Hospital that Chapin met and trained under Edward Janeway, New York City’s health commissioner. Like most physicians of his time, Janeway believed that diseases resulted from the emanations of rotting material. But Janeway was intrigued by the nascent science of germ theory, and he challenged his students to examine the problems of disease and public health in a rational and scientific manner using sound methodology. When he finally left New York City for Providence in the fall of 1879, therefore, Chapin had been exposed to the very latest ideas in medical science as well as the problems of disease and public health in a large and rather unsanitary city. In Providence, the young physician made a name for himself as a bright and capable doctor and medical researcher. His colleagues recognized his potential and nominated him for Superintendent of Public Health in 1883, a position he would hold continuously until his retirement in 1932.3

If any public health officer was capable of dealing with the devastating pandemic that struck the world in 1918, therefore, it was Charles Chapin. His training in New York City had given him first-hand experience with urban conditions and diseases, and his internship under Janeway had impressed upon him the importance of public health measures. Chapin firmly believed that a clean and healthy city was a necessity in an era when urban populations were rising quickly. As he wrote in 1889, “When a man lives by himself, he can do as he pleases and let others do the same, but when 125,000 people are gathered together on 10 square miles of land they must of necessity give up certain of their liberties. It is the sacrifice they make for the sake of the advantages of city life. The denser the population the more stringent and exacting must be sanitary regulations and indeed all other regulations. Americans, particularly those whose memories reach back to the time when are cities were villages, are prone to forget this.”4 When cholera threatened the city several times in the 1880s, Chapin and his very small staff made personal inspections of every house and tenement in the city, ordering the immediate remedy of a host of public health nuisances and problems they encountered. As Chapin’s biographer put it, “Within ten months time, more had been accomplished along this line than in the previous ten years.”5

Although a strong advocate of germ theory, Chapin nonetheless initially held many of the fundamental beliefs of late-19th century sanitarian-based public health. These included ideas about the importance of fumigation and disinfection, the need to maintain a clean urban environment, and the use of isolation and quarantine of the ill and suspected contacts. Over his years as Superintendent of Health, however, Chapin came to realize that many of the age-old methods for protecting the public’s health had little basis in scientific truth, and he had little qualms over pointing out the errors of his colleagues’ ways. Speaking at the 1906 annual meeting of the American Medical Association in Boston, Chapin delivered a paper entitled “The Fetish of Disinfection,” in which he blasted the use of terminal disinfection as a method of disease prevention. “We disinfect not because the utility of the process has been demonstrated,” he told his audience, “but because of the precedent and authority. There can be little doubt that disinfection had its origin at a time when disease was believed to be the work of demons.”6 Few agreed with his bold statements, but time would prove Chapin correct.

Similarly, Chapin did not believe in the value of isolation and quarantine once a disease had made its way into a population. “A spark in the dry grass should be stamped out at any cost, but it is useless to waste time in extinguishing the smoldering flames left here and there as the line of the fire is sweeping across the prairie,” he had written several years earlier.7 Again using the analogy of a spark and fire, Chapin wrote that “the ideal of health officers has been to keep up isolation until every spark of infection has died out, – a very reasonable ideal, until it was learned that there are many hidden sparks scattered about the community, some of which are sure sooner or later to burst into flame.”8 A sensible man, Chapin firmly believed that while bacteriologists could retreat to their laboratories, public health officers had to engage their communities daily, and thus the best solution was the one that was based on a combination of science and practicality. Trying to prevent the further spread of influenza through measures such as the closure of public places once the disease was already epidemic was, to Chapin’s mind, impractical at best and foolish at worst.

Chapin was no stranger to influenza. The disease had made regular seasonal appearances in Providence and other American cities since the epidemic of 1889-90, and in the winter of 1915 there was an epidemic in New England. That winter the Massachusetts Association of Boards of Health held a symposium on influenza, of which Chapin was a panelist.9 A few weeks later he almost died from a bout with the disease. Perhaps because of his previous experience, Chapin believed that the first cases of influenza to appear in Providence in September 1918 were of the seasonal variety. It was not until the epidemic began to roar with full force in the coming weeks that he and others up and down the eastern seaboard realized the extent of the beast with which they had to contend. The nature of the disease along with the fact that it had made significant inroads into the community led Chapin to conclude that there was little that could be done to halt the epidemic. “[W]hen the a community is pretty well sown with cases of the disease as is true of our New England cities today, the disease will run its course” he wrote. It would stop, he added, in about six weeks, “when the susceptible material is used up.”1 This is the position he took when he met with Mayor Gainer, and the case both men presented to Governor Beeckman in an attempt to derail the general closure order under consideration. No doubt Chapin’s standing in Providence, as well as in the medical and public health community, played a role in the governor’s decision to postpone such action.

The Pressure to Act

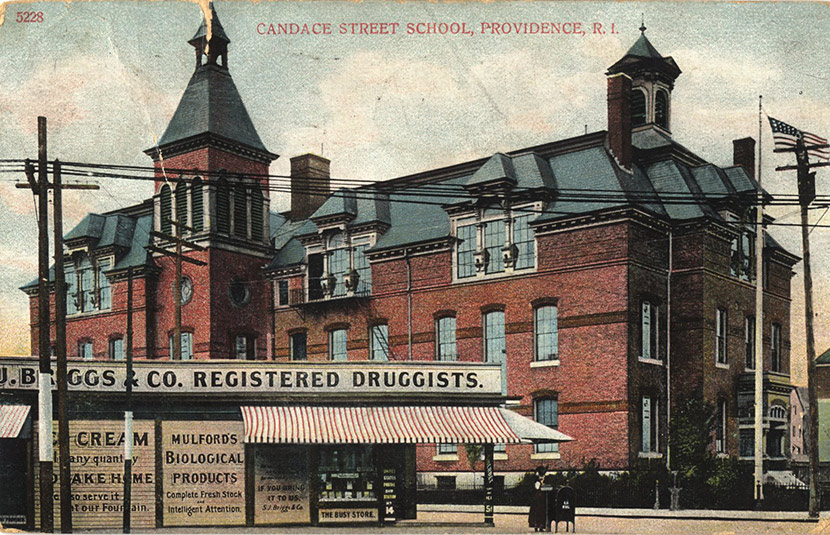

Despite Chapin’s argument that a closure order would likely do no good, public officials came under extreme pressure to do something. Cases were mounting, people were dying, and medical authorities were helpless as to the real cause of the disease. That the situation was bad was evident. But with influenza still not a reportable disease, Chapin had no real idea of how many cases were in Providence. To find out, he sent questionnaires to three hundred local physicians, asking them how many cases were under their care. On the morning of the Board of Health’s meeting he had received responses from 74 of them. The situation was not good. These 74 doctors reported a total of 1,647 cases under their care, over 900 of which they classified as new. The next day, as reports from an additional physicians arrived, the number of total cases jumped to nearly 2,500, nearly 1,200 of them labeled new. And two hundred doctors still had not yet responded to the questionnaire. Superintendent of Schools Isaac C. Winslow reported to Chapin that hundreds of cases had suddenly appeared among the city’s school children, whereas just a few days before there had been virtually none reported.11

On October 4 the state Board of Health met again to consider what measures might be taken to combat the growing epidemic. Chapin again expressed his opinion that a closure order would serve no purpose and argued that individuals could do much to prevent the spread of influenza. His was a minority view, however. After an open discussion, the state Board moved to recommend that all schools, churches, and places of public amusement across Rhode Island be closed. Later that day the Providence Board of Aldermen convened as the Board of Health (the two bodies were one in the same) and met with Chapin to discuss the possibility of a closure order in the city. The Board had just received a circular memorandum from United States Surgeon-General Rupert Blue that advised community officials to consider closing places of public assembly if and when influenza became epidemic in the area. With the passage of the state Board’s recommendation, the Blue circular, and the pressure to try something to halt or slow the spread of the epidemic, the Providence Board of Health voted to issue a general closure order. Starting Sunday, October 6, all public and private schools, theaters, movie houses, and dance halls were to close until further notice. Churches were to close their doors as well but were allowed to hold regular services one day per week.12

Chapin still believed the closure order would not effectively diminish cases nor end the epidemic any quicker, but he stated that he was not against the move. With the clamor to try anything that might work he could hardly state otherwise. A pragmatist by nature, Chapin instead focused his attention to dealing with what he knew would be a certainty: a surge in cases. He recommended that the city gather more volunteer nurses and that it increase its hospital capacity to deal with the influx of ill that would appear in the coming weeks. To help prepare for this inevitability, Chapin sent a telegram to Boston health officials recalling the nurses dispatched there in September to help that city’s epidemic, and appealed to teachers and other educated women to serve as volunteer nurses.13 Serving on an emergency influenza committee, Chapin and other health officials worked to have the city’s hospitals make more beds available for influenza victims. The Rhode Island Hospital added seventy-five beds, and St. Joseph’s added twenty-five, with the ability to add forty more if necessary. Hope Hospital, dedicated to acute surgical work, could not offer any space to flu patients, but offered its nurses’ home and billiard room as emergency hospital space if necessary. The move came none too soon, as within a few days the Rhode Island Hospital alone had nearly 300 influenza patients in its beds, some 172 said to be in critical condition. Physicians reported over 6,700 cases in the week between October 3 and October 9, although some of these were convalescent cases for which a doctor had only recently been contacted.14

Within a few days it appeared as though the worst had passed, and by October 12 the situation had improved enough for Chapin to state that the peak of the epidemic had been reached. Two days later he officially declared Providence’s epidemic over. The Board of Aldermen met to consider lifting the city’s closure order, but ultimately decided to continue the ban for at least another week out of fear that the epidemic would rear its ugly head once again if they acted too hastily.15 When the number of new cases continued to decline, the Board voted unanimously to remove the closure order effective at midnight on October 25, making good on its pledge to do so on a Friday so that entertainment venues could re-open to Saturday crowds.16 Schools re-opened on Monday, October 28 to normal student attendance. Thirty teachers were absent due to illness, but Providence was able to use substitutes from neighboring cities whose closure orders were still in effect.17

It appeared as if the worst was over, and indeed it was. Over the course of the next several weeks, as the number of new influenza cases dwindled to a small trickle, Providence residents breathed a collective sigh of relief. Their epidemic had been bad, but it was not nearly as bad as those in cities such as Boston or Philadelphia. For those who had lost loved ones the epidemic had turned from public health crisis to personal tragedy. But for those who had dodged the bullet or who had fallen ill but survived, life slowly returned to normal.

In early-December, city physicians began to notice a resurgence of influenza. Chapin was quick to state that while Providence did seem to be on the cusp of a second epidemic wave, the new cases appearing all seemed to be mild. When he received reports of high rates of school absenteeism at three particular city schools, Chapin ordered a special investigation to be carried out by school nurses. The result was confirmation of high numbers of cases among both students and teachers. Nearly a fifth of the students at Hope High School were absent due to illness, and 56 teachers among the three schools were out with the flu. Perhaps to allay any fears that the city was about to be revisited by the plague, Chapin pointed out that the number of cases of illness in the city’s schools was no higher than normal for the time of year, that the number of actual influenza cases among the absent children was low, and that the majority of absences were due to slight colds.18 As the days rolled on, however, the situation in the city’s schools grew markedly worse. By early January there were some 2,000 additional students reported absent each day, reaching a whopping 10,000 students – a quarter of the total enrollment – absent on January 3 alone. In some schools half the students were absent. It was assumed that many of these were due to apprehensive parents, but school and health officials also knew that a great number of students were indeed ill. They also knew that at that rate it would be impossible to keep the schools open for more than a few more days.19

Despite the rise in cases across the city and especially in the school system, there was little desire to take action. On December 26 the state Board of Health met and voted to add influenza to the list of mandatory reportable diseases. On December 30 the Board met again, this time to discuss the possibility of another closure order, but decided to postpone taking any action. Instead it only went so far as to issue a recommendation to the public that crowds and places of amusement be avoided.20 On January 7 the Providence Board of Aldermen met to discuss what measures to take in the city. After a two-hour discussion it was clear there was little interest in issuing another closure order and the board adjourned. During the meeting, Superintendent of Health Chapin told the board that it was impossible to know the true extent of the epidemic because of the widespread failure of physicians to report cases. In fact, less than half regularly complied and on some days only a quarter did so; among the offenders were two members of the Rhode Island board of health. Chapin suggested shaming non-compliant doctors. “The whole matter of reporting the cases becomes a farce,” he told the Board. “If we cannot get them all reported, I would favor publishing the names of the physicians each day in the newspapers who fail to comply with the law.” The Board felt that such action would hurt the public, and instead resolved to send these physicians letters of warning.21

For the next several weeks the numbers of reported cases of influenza as well as the tallies of absent students fluctuated, rising on certain days but never reaching the height that it had during the peak of the previous wave. By the end of January the situation had improved substantially, and the city once again breathed a sigh of relief. Early-February saw the lowest case tallies in months, and February 5 was the first day since the epidemic had started that no new cases were reported.

Attention turned away from the epidemic and to its aftermath. The city’s charitable organizations, the only safety net that existed, had been taxed to the limit by the epidemic. The coffers of the Providence Society for Organizing Charity, for example, were depleted by the crisis. The Society had cared for 516 cases during the epidemic, and 39 of the 76 cases under its care that resulted in death were primary breadwinners. These families now had no means of support, and the Society pledged to take care of them. It had spent $1,880 for influenza cases in 1918 alone, and expected to spend an additional $1,500 cases to cover its epidemic-related expenses for the first months of 1919. This did not include other associated expenses. An appeal to Providence residents for donations resulted in a quick influx of cash, but the Society was still short nearly $3,500. And it was just one of several such charitable organizations. The pandemic in Providence, just as elsewhere, had not only destroyed the lives of those lost to it, but also to those who had to struggle through its aftermath.

Notes

1 “State Health Board Acts to Combat New Disease,” Providence Daily Journal, 28 Sept. 1918, 5.

2 “Assembly Places Not to Be Closed,” Providence Daily Journal, 29 Sept. 1918, 1.

3 James H. Cassedy, Charles V. Chapin and the Public Health Movement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 1-30.

4 Charles V. Chapin, “Sanitary Administration of Cities (unpublished manuscript, 8 Feb. 1889), 65, Rhode Island Medical Society Library, Providence, Rhode Island, quoted in Cassedy, 41.

5 Cassedy, 46.

6 Charles V. Chapin, “The Fetich of Disinfection,” in Frederic P. Gorham and Clarence L. Scamman, eds., The Papers of Charles V. Chapin, M.D.: A Review of Public Health Realities (New York: Commonwealth Fund, 1934), 66.

7 Charles V. Chapin, The Sources and Modes of Infection, 2nd edition (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1912), 257.

8 Ibid., 150.

9 “Former Outbreaks of Influenza,” Providence Daily Journal, 14 Feb. 1920, and M. J. Rosenau, F. X. Mahoney, J. C Coffey, and Charles V. Chapin, “Influenza and Pneumonia,” American Journal of Public Health 6 (April 1916), 307-322.

10 Chapin, “Medical Facts and Theories: Influenza,” Sept. 28, 1918, Series 2, Box 2, Folder 72, Charles V. Chapin Papers, MS343, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, RI.

11 “Providence May Close Public Assembly Places,” Providence Evening Bulletin,” 4 Oct. 1918, 4.

12 “All Places of Public Assembly In This City Ordered Closed,” Providence Daily Journal, 5 Oct. 1918, 1.

13 “Local and Navy Authorities Act to Combat Spread of Influenza,” Providence Daily Journal, 4 Oct. 1918, 1, and “Victory-Columbus Day Parade Cancelled Owing to Epidemic,” Providence Daily Journal, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

14 “Influenza ,Epidemic Apparently Unchecked, Adds 55 R.I. Deaths,” Providence Daily Journal, 6 Oct. 1918, 1, “32 More Deaths From Influenza Are Reported in Rhode Island,” Providence Daily Journal, 9 Oct. 1918, 1; “Influenza Situation in This State Now Showing Slight Improvement,” Providence Daily Journal, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

15 “Brunt of Epidemic Believed Met Here,” Providence Daily Journal, 13 Oct. 1918, 2; “Peak of Influenza Is Past, Dr. Chapin Thinks,” Providence Evening Bulletin, 14 Oct. 1918, 8; “Peak of Epidemic Is Believed Past,” Providence Daily Journal, 15 Oct. 1918, 5; “Ban on Public Gatherings in City Continues,” Providence Evening Bulletin, 18 Oct. 1918, 9.

16 “Ban on Public Gatherings Will Be Lifted at Midnight To-Night,” Providence Daily Journal, 25 Oct. 1918, 3.

17 “Schools Reopen; Attendance Is Good,” Providence Daily Journal, 29 Oct. 1918, 12.

18 “City Experiencing Mild Influenza Recrudescence,” Providence Daily Journal, 7 Dec. 1918, 11; “Health of School Children Watched,” Providence Daily Journal, 14 Dec. 1918, 3; “School Sickness Is Not Alarming,” Providence Daily Journal, 15 Dec. 1918, 7.

19 “10,000 Children Out of Schools,” Providence Daily Journal, 5 Jan. 1919, 4.

20 “Influenza Spread Arouses Officials,” Providence Daily Journal, 29 Dec. 1918, 4.

21 “Influenza Cases Must Be Reported,” Providence Daily Journal, 27 Dec. 1918, 14; “Mayor Considers Influenza Status,” Providence Daily Journal, 3 Jan. 1919, 5; “Aldermen Confer on Influenza Ban,” Providence Daily Journal, 8 Jan. 1919, 14; “Death Rate Takes Big Jump in City,” Providence Daily Journal, 9 Jan. 1919, 3.

Click on image for gallery.

People gather around the public drinking fountain at Roger Williams Park in Providence. Designed in 1878 and completed in the 1880s, the large park on the southern end of town quickly became a popular place for residents to relax and escape the city. Drinking fountains such as this one, commonly known as “bubblers,” were just one of the ways in which diseases could be spread. During the pandemic, many public health officers around the nation worried that they would spread influenza as well.

Click on image for gallery.

People gather around the public drinking fountain at Roger Williams Park in Providence. Designed in 1878 and completed in the 1880s, the large park on the southern end of town quickly became a popular place for residents to relax and escape the city. Drinking fountains such as this one, commonly known as “bubblers,” were just one of the ways in which diseases could be spread. During the pandemic, many public health officers around the nation worried that they would spread influenza as well.