Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Washington, DC

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

As the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. theoretically was better positioned to deal with the 1918 influenza pandemic than any other American city. Along with the city’s own Health Officer, Dr. W.C. Fowler, the United States Surgeon General Rupert Blue and Public Health Service staff were at hand to try to stem the rising tide of the disease. They had good reason: Washington, D.C. was not only the Nation’s political center but its military one as well. Unfortunately, the state of medical science, the rapidity with which the disease struck, and some political mismanagement did much to hamper efforts to control the deadly epidemic. As a result, Washington, D.C. suffered one of the worst epidemics in the nation.

Washington newspapers first began reporting the appearance of influenza cases in the city in the last week of August, although it is likely that the disease was circulating well before that due to the large number of incoming and outgoing military personnel.1 Initially, however, it was assumed that influenza was mainly a military problem that was circulating throughout naval stations and army camps and might not become widespread amongst civilians. On September 26, Health Officer Dr. W. C. Fowler warned the public to be cautious about influenza, but he did not believe that threat of a large-scale epidemic was serious. Within a few days, however, as reports of additional civilian cases and a few deaths trickled into his office, Fowler became slightly more concerned.2 He recommended that citizens stay off streetcars if possible and asked organizations to postpone all unnecessary meetings until the danger of influenza had passed. He did not yet believe there was reason to order a ban on public gatherings, however.3 “There is little danger that Washington, with its high degree of wholesomeness, will be the scene of serious outbreak of the disease,” Fowler announced.4

Health Officer Fowler and other district officials quickly changed their tune, however. On the morning of Wednesday, October 2, the school board decided to close all public schools effective at noon, sending approximately 50,000 students home for the duration of the epidemic. Fowler requested that private schools do the same, and all agreed. Louis Brownlow, District Commissioner, ordered the cancellation of all public gatherings (including public funerals) and the closure of churches, theaters, and movie houses effective October 3. All other businesses and shops were placed on a staggered operating-hours schedule to help alleviate streetcar congestion. Physicians were ordered to report all cases of influenza to the Health Department. Fowler, himself ill with what was reported to be influenza, issued a one-page circular on the disease’s prevention and treatment, to be sent to every household in the city. Officials ordered playground hours extended and promised additional equipment to entice children to get as much fresh air as possible. Commissioner Brownlow also announced that he was collaborating closely with Public Health Service officials to meet the challenges presented by the epidemic crisis.5

The next day, Brownlow ordered churches and Sunday schools closed and barred children from city playgrounds. He also ordered physicians to report all influenza cases and to isolate all patients as stringently as possible; the fine for failing to do either was a whopping $50. Public libraries were closed. George Washington University closed, and Georgetown University suspended regular classes while the school’s Student Army Training Corps units were placed under a campus-wide quarantine. The federal government even took action, closing the Library of Congress and the Senate and House galleries, and postponing public court hearings. Army medical officers stationed in the city were tasked with helping civilian physicians with their caseloads.6 Washington, D.C. had finally gotten serious about its epidemic.

It was none too soon. The situation was growing worse by the day, with nearly 3,000 cases total officially reported in the city. Shortly after the epidemic had begun, the United States Public Health Service had opened a temporary emergency hospital at 612 F Street, NW.7 That hospital was quickly overwhelmed. Officials then divided the city into five districts and established temporary headquarters in school buildings in each of them. These district headquarters would be used to direct local physicians and nurses more efficiently to influenza cases, hopefully cutting down on transportation times and service overlap.8 To relieve pressure on hospitals, four emergency relief centers and an emergency hospital were established across Washington, D.C. Initially, each was staffed with one physician and twelve nurses, but within a few days federal officials stepped in to help, tasking army and navy doctors to assist.9 Soon, however, even this augmented staff was overwhelmed with cases. The Red Cross put out desperate calls for trained nurses as well as untrained volunteers to help at the emergency centers.10 Unfortunately, African Americans were largely on their own, as the centers were for white residents only. Not until late-October did a relief station for Washington, D.C.’s African American residents open, located at the Armstrong Manual Training High School at 1st and P Streets, NW.11

On October 9, church leaders met with District Commissioner Brownlow in an attempt to have churches removed from the list of closed institutions. Brownlow absolutely refused. Outdoor meetings, however, were still allowed. Believing that churches thus could dodge the closure, on October 10, the Board of Commissioners added all outdoor meetings to the list of prohibited gatherings.12 Two days later, Brownlow met with Surgeon General Rupert Blue to discuss the problem of the massive influx of war workers entering Washington, D.C. Brownlow, Fowler, and some congressional representatives wanted the city closed to outsiders until the epidemic had passed, as the sheer number of newcomers was causing congestion on the mass transit lines and in housing. Federal authorities denied the request, which they argued was impossible to enforce. Instead, they asked the Civil Service Commission to stop calling war workers to Washington, D.C. until after the danger of the epidemic had passed. Secretary of Treasury William McAdoo and Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane responded by ordering their departments to stop recruiting workers from outside the Washington, D.C. area.13

By the last week of October, the city’s influenza situation seemed to be improving. Physicians were reporting fewer numbers of new cases each day, and hospitals were seeing a decrease in admissions. With the good, if still tentative, news, Fowler came under increasing pressure to remove the ban on public gatherings. He refused, stating that he would not recommend lifting the ban for some time to come. The Board of Education set the tentative school reopening date for Monday, November 4, a move with which Fowler strongly disagreed. “Tremendous pressure is being brought to bring about the reopening of the public schools, theaters and churches, but, in my opinion, it is yet too early to throw off the safeguards,” he told reporters. Some of this pressure came from clergy, upset that their churches were closed while department stores, poolrooms, and bowling alleys were allowed to conduct business as usual. One pastor questioned the church closure order altogether, arguing that it disrupted “the normal religious life of our city,” and was a virtual admission that “the Lord’s hand is shortened, that it cannot save!” Yet Fowler and Brownlow agreed that it was still too soon to consider reopening public places, and urged residents to stay the course until all danger of the epidemic had finally passed.14

The very next day, however, Fowler abruptly changed his mind and recommended that the closure order be lifted. On October 29, the district commissioners followed his advice and rescinded the ban. Churches would be allowed to reopen on Thursday, October 31, and schools and theaters on Monday, November 4.15 Children would make up lost classroom time through a combination of a revised and intensified curriculum and reduced future vacation time, but officials felt confident that extra days would not have to be added to the academic calendar.16

Meanwhile, the number of new influenza cases and deaths in the nation’s capital continued to decline. Throughout November it appeared as if the epidemic would soon burn itself out completely. On November 24, the city commissioners removed the restrictions on business hours that had been in place for nearly two months.17 Residents went about their business wary of a potential return of the disease, but hopeful that the worst had passed.

By early-December, however, influenza cases began spiking again, with some days seeing several hundred cases being reported by physicians. Fowler was not surprised, and had been warning that a recurrence of the disease was likely. He kept a close eye on influenza in the city’s schools, seeing classrooms as a barometer for how bad the situation really was. On December 11, he discussed the possibility of a second school closure with Superintendent of Schools Ernest Lawton Thurston, and the two men agreed that keeping classrooms open would prevent children from crowding in downtown stores during the busy holiday shopping season. Two days later, with new case tallies approaching 350 per day, Fowler told the city commissioners that it might be time to close schools, churches, and theaters once again. After some debate, however, they decided to take no action. The city remained open.18

By this time, Washington’s emergency hospitals had closed. The health department reopened the F Street emergency facility on December 19 to handle the new cases. With insufficient funds to run the hospital, however, the department had to rely heavily on funding from the Public Health Service, the American Red Cross, and the medical department of the Army.19

Washington D.C.’s influenza epidemic continued throughout the rest of the year and into early-February 1919, albeit with reduced case numbers. Between October 1, 1918 and February 1, 1919, some 33,719 Washington residents fell ill with influenza, with 2,895 of them succumbing to the disease.20 The result was one of the more devastating epidemics in the nation: an excess death rate of 608 per 100,000.

Notes

1 “Death Here from Spanish Influenza,” Washington Evening Star, 21 Sept. 1918, 2, and “Influenza Kills Here,” Washington Post, 22 Sept. 1918, 3.

2 The first civilian death in Washington, D.C. was reported on September 21. See Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, Year Ended June 30, 1919, Vol. III: Report of the Health Officer (Washington, D.C.: 1919), 16.

3 “Influenza Brings Death to 3 More,” Washington Evening Star, 27 Sept. 1918, 1.

4 “Washington and the Influenza,” Washington Evening Star, 29 Sept. 1918, 2.

5 “City Fights Grippe with Severe Steps,” Washington Post, 3 Oct. 1918, 1; Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, Year Ended June 30, 1919, Vol. III: Report of the Health Officer (Washington, D.C.: 1919), 16.

6 “Flu Still Spreads,” Washington Post, 5 Oct. 1918, 1; “Army Physicians to Aid Neighbors,” Washington Evening Star, 4 Oct. 1918, 19; “Thirty-one Die from Influenza Here in 11 Hours,” Washington Evening Star, 6 Oct. 1918, 1; “Decrease Shown in Deaths from Influenza in D.C.,” Washington Evening Star, 7 Oct. 1918, 1; “Decrease Shown in Deaths from Influenza in DC,” Washington Evening Star, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, Year Ended June 30, 1919, Vol. III: Report of the Health Officer (Washington, D.C.: 1919), 17.

8 “12 More Deaths from Influenza in the District,” Washington Evening Star, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

9 “No Crest Yet in Flu,” Washington Post, 9 Oct. 1918, 1, and “76 Army and Navy Doctors are Detailed to New Flu Station,” Washington Post, 12 Oct. 1918, 4. The emergency centers were established at the Curtis School in Georgetown, the Wilson Normal School at Fourteenth and Harvard Streets, NW, the Webster School at Tenth and H Streets, NW, and the Van Ness School at Fourth and M Streets, SE. The 500-bed emergency hospital was established at 19th Street and Virginia Avenue, NW. See, “83 Deaths in Day from Influenza,” Washington Evening Star, 16 Oct. 1918, 19.

10 “New Flu Hospital,” Washington Post, 14 Oct. 1918, 1.

11 “Epidemic Recedes, View of Officials,” Washington Evening Star, 21 Oct. 1918, 1. Armstrong’s most famous student was Duke Ellington, who studied commercial art at the school. This does not seem to be relevant.

12 “No Crest Yet in Flu,” Washington Post, 9 Oct. 1918, 1; “47 More Die of Flu,” Washington Post, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

13 “74 Die, High Record, and 1,594 Cases,” Washington Post, 12 Oct. 1918, 1, and “D.C. Deaths Fall to 65 in Today’s Influenza Report,” Washington Evening Star, 12 Oct. 1918, 1; “88 Deaths by Flu, High Record in City,” Washington Post, 16 Oct. 1918, 1.

14 “Reopening the Schools,” Washington Post, 23 Oct. 1918, 6, “Closing of the Churches,” Washington Evening Star, 26 Oct. 1918, 7, and “Epidemic Decline Seen by Officials,” Washington Evening Star, 28 Oct. 1918, 2.

15 “Movies, Schools, and Churches are to Be Reopened,” Washington Evening Star, 31 Oct. 2.

16 “School Officials Plan for Current Semester,” Washington Evening Star, 30 Oct. 1918, 7.

17 “Stores Will Open Early Tomorrow,” Washington Post, 24 Nov. 1918, 24.

18 “408 Influenza Cases in City since Nov. 26,” Washington Evening Star, 2 Dec. 1918; “313 New Flu Cases,” Washington Post, 11 Dec. 1918, 8; “Influenza Cases Take a Big Jump,” Washington Evening Star, 12 Dec. 1918, 2; “Plan Drastic Step to Halt Influenza,” Washington Evening Star, 13 Dec. 1918, 2; “Public Gatherings Not to Be Stopped,” Washington Evening Star, 14 Dec. 1918, 2.

19 Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, Year Ended June 30, 1919, Vol. III: Report of the Health Officer (Washington, D.C.: 1919), 17.

20 Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, Year Ended June 30, 1919, Vol. III: Report of the Health Officer (Washington, D.C.: 1919), 18. The mortality figure also includes 680 deaths due to pneumonia brought on by influenza.

Click on image for gallery.

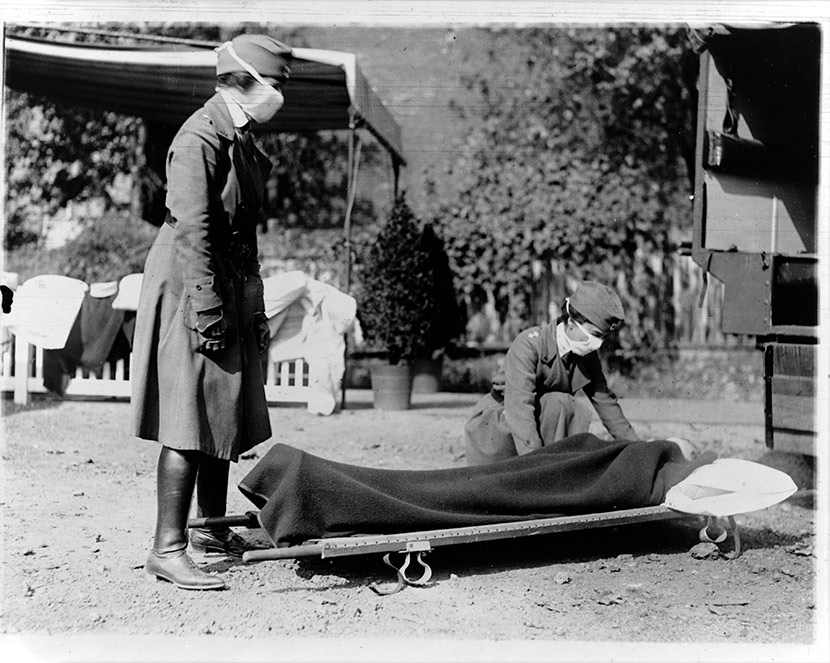

Men on troop train, with Red Cross workers in front. Scenes like this were common throughout the war period and during the epidemic.

Click on image for gallery.

Men on troop train, with Red Cross workers in front. Scenes like this were common throughout the war period and during the epidemic.

Click on image for gallery.

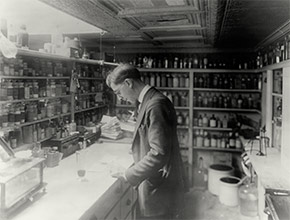

A pharmacist at People’s Drug Store No. 5, at 8th and H Streets, NE, Washington, DC. During the epidemic, residents flocked to druggists to purchase a host of medications for influenza, many of them little more than snake-oil curatives.

Click on image for gallery.

A pharmacist at People’s Drug Store No. 5, at 8th and H Streets, NE, Washington, DC. During the epidemic, residents flocked to druggists to purchase a host of medications for influenza, many of them little more than snake-oil curatives.

Click on image for gallery.

Workers from the Munitions Building in Washington, DC are served hot chocolate, October 24, 1918. Large crowds like this undoubtedly helped spread influenza.

Click on image for gallery.

Workers from the Munitions Building in Washington, DC are served hot chocolate, October 24, 1918. Large crowds like this undoubtedly helped spread influenza.

Click on image for gallery.

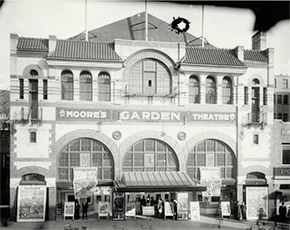

Moore’s Garden Theater, at 425-433 9th Street, NW, at the corner of E Street, NW in Washington, DC. Originally the Imperial vaudeville theater, it was renamed in 1913 and became a movie house in 1918. During the epidemic, Moore’s was one of many public entertainment venues across the city – and across the United States – that was closed in an attempt to bring about a quicker end to the deadly plague.

Click on image for gallery.

Moore’s Garden Theater, at 425-433 9th Street, NW, at the corner of E Street, NW in Washington, DC. Originally the Imperial vaudeville theater, it was renamed in 1913 and became a movie house in 1918. During the epidemic, Moore’s was one of many public entertainment venues across the city – and across the United States – that was closed in an attempt to bring about a quicker end to the deadly plague.