Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

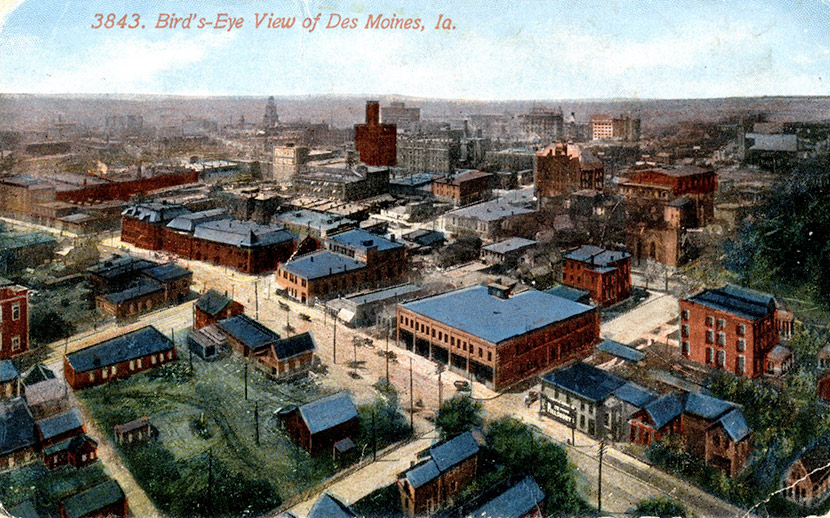

Des Moines, Iowa

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

October 10, 1918. “Des Moines goes under quarantine today.” Thus read the first line of a front-page article on the influenza epidemic in the city’s newspaper, the Des Moines Register. Influenza had been circulating in the city for the past two weeks, but the number of cases reported had been small. It was at Camp Dodge, a dozen miles or so northwest of Des Moines, where the epidemic was raging. There, as many as 3,000 soldiers were ill. City officials knew, however, that it was only a matter of time before the epidemic hit civilians with the same vigor. For that reason, the Board of Health voted to close all churches, schools, and places of amusement and congregation. Residents were asked to remain at home if they began to experience symptoms of illness as state law did not permit the mandatory quarantining of influenza cases. Officials knew that such measures would not prevent an epidemic, but hoped that it would reduce the total number of cases and spread them out across a longer time period so as not to overwhelm Des Moines’ healthcare infrastructure.1 It was an incredibly sophisticated understanding of how best to handle an influenza epidemic, one that was lacking in most other American cities at the time.

The war placed Des Moines in a unique, if difficult, position. Many large cities had military camps nearby, but few were as close as Camp Dodge was to Des Moines. Medical officers had placed the camp under quarantine, barring soldiers from leaving or visitors from entering. Camp Dodge, however, was still in the midst of construction, requiring laborers from the city. The result was a daily movement of civilians to and from the camp and an inevitable intermingling of soldier and residents. To compound the problem, these laborers crowded the early-morning streetcars in order to get to the job site. Despite restrictions on streetcar crowding, officials had little choice but to bow to wartime exigencies and modify the order: laborers could fill streetcars up to twenty-five people over seating capacity until 7:30 am, after which time the normal anti-crowding measures would resume.2

By this time, however, it appeared as though the epidemic at Camp Dodge had passed its peak.3 The real danger, then, was to the civilian population. Yet the epidemic in Des Moines had not been especially severe, and peaked shortly after that at Camp Dodge. On October 28, the health board lifted the closure order and gathering ban, a move most members had supported earlier but chose to err on the side of caution.4 Residents were once again free to catch a movie or attend the theater, while children returned to their classrooms with attendance only slightly reduced. The School Board later voted to reduce the Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday breaks in order to make up the lost classroom time, a problem compounded by the need to release male students in time for the spring planting season.5

Des Moines was not out of the woods yet, however. With the social distancing measures removed, influenza cases began to increase once again. The School Board reinstated the Friday after Thanksgiving as a holiday in an attempt to control the spread of the disease among schoolchildren.6 A few days later, they closed schools completely. Dr. Woods Hutchinson, a national health figure and vocal advocate of flu masks, visited Des Moines and began preaching their benefits. Shortly thereafter, the Board of Health issued a recommendation to residents to wear masks while in public. On December 2, the Board made that recommendation mandatory: as of noon that day, the wearing of face masks was required in all public places such as theaters and even college classrooms, but were not required in streetcars, office buildings, or stores and shops. Interestingly, theater and movie house operators were willing to close to bring about a quicker end to the epidemic, but were asked by the Board of Health to remain open. “We think a certain amount of amusement is necessary,” commented Commissioner of Public Safety Ben Wolgar.7

The mask order did not last long. Theatergoers were unhappy that they had to wear masks while watching stage performances or movies, and theater owners were unhappy that they had to enforce the order in their establishments. Box office receipts fell drastically. At the Garden Theater, for example, six hundred patrons attended the December 2 matinee show, before the mask order went into effect; only two hundred attended the evening performance. Across the city, theaters and movie houses reported half of the usual attendance. Many Des Moines residents, it seemed, so disliked wearing flu masks that they preferred to remain at home rather than to don one. Bending to the will of the people and business interests, and with the support of physicians who (correctly) argued that gauze masks did little to prevent the spread of influenza, the Board of Health revoked the order on December 4 and once again made the wearing of flu masks voluntary.8

Control measures were still needed, however, as the number of new influenza cases continued to rise. The day the mask order was removed was the single worst day of the epidemic, with nearly 500 cases reported. On December 6, the Board of Health issued a set of social distancing measures after conferring with business and labor leaders. All dance halls, skating rinks, outdoor sporting venues, consignment stores, and improperly ventilated shops were ordered closed. Other places of public amusement were limited to half of their seating capacity. Schools were included in the list, but were effectively already closed by order of the board of education. Churches were allowed to remain open but Sunday schools were closed. Most clergy were of the opinion that regular services should not be held until all danger had passed. The order was slated to remain in effect until at least December 16.9

By the time that date approached, the influenza situation had begun to improve once again. On December 16, social distancing measures were removed and Des Moines residents were once again able to attend dances, go to football games, and ice skate in the city’s rinks. The Board of Education, however, decided to play it safe and keep schools closed through the upcoming Christmas holidays. When schools finally reopened on December 30, officials were pleased to find attendance was back to normal.10

Notes

1 “Quarantine’s Lid Settles over City,” Des Moines Register, 10 Oct. 1918, 1; “Red Cross Unites to Fight Plague,” Des Moines Register, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

2 “Quarantine Gives Epidemic Control,” Des Moines Register, 12 Oct. 1918, 6.

3 “Camp Dodge Flu Situation Better,” Des Moines Register, 13 Oct. 1918, 6.

4 “Quarantine Rules to Be Lifted Today,” Des Moines Register, 28 Oct. 1918, 3. On October 18, as influenza raged across much of Iowa, the state board of health enacted a state-wide closure order and gathering ban. As conditions in Des Moines improved, the state board made it clear that communities had the authority to lift the closure order as they saw fit and in response to local conditions. See, “State Quarantine is Now in Effect,” Des Moines Register, 18 Oct. 1918, 8, and “Quarantine Relief is Expected Soon,” Des Moines Register, 24 Oct. 1918, 6.

5 “Schools May Lose Holiday Vacation,” Des Moines Register, 3 Nov. 1918, 5, and “Cut School Vacations,” Des Moines Register, 6 Nov. 1918, 8.

6 “Schools Given Holiday,” Des Moines Register, 27 Nov. 1918, 10.

7 “Flu Mask Edict Is in Effect Tonight,” Des Moines Register, 2 Dec. 1918, 1. Theater and movie house owners believed that a mask ordinance would be too difficult to enforce on their premises, and so preferred a complete closure order. See “Flu Precaution Is Yet to Be Decided,” Des Moines Register, 30 Nov. 1918, 10.

8 “Mask Regulations Go into Operation,” Des Moines Register, 3 Dec. 1918, 1.

9 “New Flu Program Effective Today,” Des Moines Register, 6 Dec. 1918, 1.

10 “Flu Restrictions Are Terminated,” Des Moines Register, 17 Dec. 1918, 1; “School Attendance Good,” Des Moines Register, 31 Dec. 1918, 5.