Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Salt Lake City

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

While the rest of the nation mobilized to fight influenza in the fall of 1918, Salt Lake City looked like it might be spared from the dreaded epidemic. As September rolled into October, no cases were reported in town. Residents certainly knew of the epidemic raging across the United States, having received regular news of influenza since at least mid-September.1 On September 27, the health commissioner of the Salt Lake, Dr. Samuel G. Paul, told residents that, while influenza was high contagious, it was also readily preventable with just a little care on the part of the public. He warned that the disease was spread through particles released by coughing or sneezing, and that covering your mouth and nose with a handkerchief would greatly reduce the dissemination of the germ. He added that, in the event influenza made its way to Salt Lake City, the Board of Health would take whatever action it thought necessary to fight the epidemic.2

On the afternoon of October 4, the Salt Lake City Board of Health met to discuss the small number of influenza cases that had been discovered in the city and to decide what action to take to try to stop the disease from spreading. The Board believed that there were eight to ten cases, all spread from a family from Wyoming that had come to attend the state fair. The health department had isolated all of the cases. At the state level, Dr. T. B. Beatty, Utah’s health commissioner, ordered physicians to report all cases and to isolate all patients.3 Both Paul and Beatty expected more cases to appear in Salt Lake City and across Utah. Later that day, Beatty requested that town officials in Coalville, some 40 miles northeast of Salt Lake City, close schools and places of public gathering after a dozen influenza cases were discovered there. For the time being, Salt Lake health officials did not feel the situation was serious enough to take action beyond the isolation of cases.4

Within a week, several dozen new cases and a handful of deaths were reported in Salt Lake City. The situation was similar in other communities across Utah, including in nearby Coalville, where even the mayor and his family had fallen ill with influenza.5 State health commissioner and the Utah board of health decided that action was needed, and on October 9 ordered closed all churches and Sunday schools, public schools and universities, theaters, movie houses, public meetings, pool halls, dance halls and private dances, and prohibited public gatherings of all kinds, effective the morning of October 10.6 Utah was shut down.

In Salt Lake City, health officer Paul was upset by the state order. “The general closing order,” he said, “is mere hysteria. There is no occasion whatever for closing down any business, and certainly no good reason whatever for closing the public schools.” He was most bothered by the fact that state officials did not bother to ascertain the situation in Salt Lake City before issuing the order. He believed that children were best left in schools, arguing that they would mingle as much out of school as they would in their classrooms. More effective than the closing order, he argued, would be an order to prohibit funerals (because surviving family members would most likely have had contact with the deceased and would likely have influenza themselves) or an order to keep streetcars well ventilated.7 Paul had not issued either of these two purportedly more effective measures, however.

To prepare for the worst, Red Cross officials hurriedly began renovating Judge Mercy Hospital for emergency use to isolate as many patients as possible. Beatty asked all city hospitals to stop accepting influenza patients as soon as the new hospital was ready, in the hopes of containing all the cases there.8 Red Cross volunteers worked with amazing speed to have the new facility operational in three days, opening the doors for influenza patients on October 13.9

On October 16, military offices at Fort Douglas–located on the outskirts of the city–issued a wholesale quarantine of the military post. To prevent the spread of influenza either into or out of the fort, Captain and post commander J. O’C. Hunt announced that all civilian visitors would be barred from entering the post, and all soldiers prohibited from leaving. Under very strict guidelines, relatives of very sick soldiers–there were several dozen cases among soldiers and University of Utah Student Army Training Corps cadets–would be permitted to enter the base to visit their kin. Delivery wagons and government vehicles would continue to be made, but the number of incomers would be kept to a minimum and their time on the post limited to as short a duration as possible.10

Meanwhile, the epidemic was growing worse among Salt Lake City’s civilian population. Over one hundred new cases of influenza were reported to the city board of health on October 18 alone, among them an increasing number of children and young adults.11 The death toll was also rising.12 Two days later, however, as the daily tally for new cases dropped, health authorities in the city declared that the peak had been reached and that the epidemic would begin to subside over the coming days and weeks.13 In fact, the new cases kept mounting.14 Unable to stem the tide, the Utah board of health discussed a statewide mask order at its meeting on October 25. The belief, or at least hope, was that the wearing of masks would spare Utah towns and cities the incredibly high case and death toll that plagued the East Coast. “No person need fear influenza if the protective gauze mask is worn,” Beatty announced. He even stated that the mask need not fit tightly in order to function, but could simply drape over the nose and mouth. The resolution called for all people in offices, businesses, or public places (except on the street) to wear a mask.15 In the end, the mandatory mask order was not put into effect.

The epidemic in Salt Lake City rolled on, gaining momentum. On October 28, 147 cases and 11 deaths were reported. It was the single highest case tally to date. The local chapter of the Red Cross was swamped with calls for help. Eight of the most urgent calls of the day went unanswered for lack of nurses. 16 As the month came to a close, the epidemic numbers began to look increasingly grim. Over 2,400 cases had been reported since the start of the epidemic, with nearly 130 deaths.17 Beatty and the Utah board of health were at a loss as to how to control the disease. Believing that the latest cases were primarily among family members of patients who were transmitting it to others, they resorted to placarding all houses of influenza patients. Family members and necessary caretakers were to don gauze masks when in the house. Beatty warned that failure to comply with the placarding rules would result in the entire house being placed under quarantine, undoubtedly causing a severe hardship for the family.18

Finally, on the last day of October, authorities believed the city had rounded the bend in the epidemic, although they were quick to discourage false hope in the latest influenza tallies.19 As October gave way to November, the trend held. By November 8, Salt Lake City health commissioner Samuel Paul announced that the emergency hospital would likely be closed soon for lack of new patients. Beatty announced that the closure orders would be lifted in three Utah towns within a few days, hinting that the ban soon would be removed from the entire state as conditions warranted.20 Three days later, on November 11, only twenty-two patients were in the emergency hospital, and Paul ordered that no new patients be admitted there unless the epidemic returned.21 The next day, the hospital was closed and the fourteen remaining patients were either sent home or transferred to regular city hospitals.22 The outlook in Salt Lake City was beginning to shape up for the better.

The Armistice Day celebrations put a kink in the plans, however. Because of the large-scale public gatherings, Beatty was concerned that the epidemic would once again begin to rage. He therefore deferred consideration of re-opening schools in Salt Lake City until the effects of the celebrations on the epidemic could be studied. “There were so many opportunities for close contact in the crowds and among the dancers of Monday” Beatty said on Wednesday, November 13, “that if there is still an active epidemic character to the infection, it will lead to a sharp increase in the number of cases.”23 Sure enough, reports for the following day–125 new cases–indicated a rise. Dr. Paul was less alarmist, arguing that 44 of those cases were not new and that 25 of them were not checked before the statistics were released. Beatty believed caution was the better part of valor, however, and refused to lift the closure order. “We would be taking chances on losing all we have gained through the restrictive measures if we rescinded the closing order at this time,” he announced.24 The closure order was to stay in place for the time being.

School officials were eager to reopen their classrooms. On November 20, Superintendent Ernest Smith announced that, in order to fit the necessary work into the remainder of the school year, all non-essential portions of the curriculum would have to be removed. The school board developed a plan that would approximate a year’s-worth of study and compress it into the time available. As part of this plan, holidays would be shortened but not removed. Smith hoped that the revised curriculum would suffice. He also hoped that all the high school students would return to the classes once schools reopened. The fear was that many had taken the impromptu “vacation” created by the closure order to obtain jobs. Smith hoped that Beatty would allow schools to reopen by November 25.25

That same day, a committee of five businessmen was appointed to help devise measures to combat the epidemic that would be both effective as well as amenable to the business community. The group believed that the isolation of cases would be most effective. 26 It also proposed staggering business hours to prevent crowding in streetcars and shops. Grocers, clothing and department stores, and five-and-dime shops would be regulated, while restaurants, cafes, and drug stores would maintain their normal hours but could not allow crowds to form.27 City and state health officials approved the plan and put it into effect on the morning of November 22. In addition to these staggered business hours, passenger limits were placed on streetcars (75 for large cars, and 50 for small ones), and shops were prohibited from holding or advertising sales. One committee member, annoyed that such measures were required, blamed the public for failing to prevent the spread of the epidemic. “If the public had cooperated with the board of health and followed the suggestions of Dr. Beatty more closely,” he said, “it is likely the epidemic would have been under control before now.”28

Over the course of the next week, as November gave way to December, the epidemic situation in Salt Lake City seemed to improve slowly. Beatty was still cautious and not yet ready to lift the closure orders, however. Instead, the board of health considered issuing a mandatory mask order in the hopes that it would stamp out the disease once and for all. On the evening of November 29, city physicians, Fort Douglas medical officers, city and state health officials, and representatives of the business community met to discuss the possibility of a mask order. The majority of physicians present objected to the use of masks by the general public, arguing that they hand only minor preventive effects at best. A mask order, they believed, would entice people to relax their vigilance, owing to the false sense of security the gauze provided.29 “Even if used intelligently,” Beatty said, “The value of the mask has been considered only relative, and no such as to justify the weakening of the efforts of the health authorities to emphasize and enforce the real and vital measures for the control of the disease.” In the end, the Utah board of health decided against passing a mandatory mask order.30

Instead, authorities relied heavily on quarantining households with influenza cases and on a public vaccination campaign, using both the Leary and Rosenau sera in the hopes that together they would provide protection from influenza and pneumonia. Free inoculation clinics were established across the city, and all residents were urged to get their vaccination.31 As thousands of residents lined up for their vaccinations and as city authorities worked hard to isolate cases and quarantine infected households, and, more important, as the epidemic naturally ebbed, Beatty began to feel more comfortable with the prospect of lifting the closure order.32 On Friday, December 6, the state and city boards of health met and unanimously voted to modify the closure order. Churches would be allowed to reopen on Sunday, and theaters could open for business once again starting on Monday. Schools would remain closed until at least the end of the year, however, and dances and public gatherings were still prohibited.33 The thousand or so workers who had been without unemployment due to the closure order were happy to return to their jobs, and their paychecks.34 Children were undoubtedly happy about their closure remaining in place, but school officials were not. Teachers still needed to be paid, and missed instruction time still needed to be made up. The board of education believed that public schools were less likely to be places of contagion than were theaters and movie houses, and passed a resolution calling on the health department to give preference to reopening schools over theaters and movie houses.35 To placate school officials, theater and movie house managers unanimously voted to exclude children under 14 from their establishments until the schools were reopened.36

As Salt Lake City slowly reopened, other Utah communities moved in the opposite direction. Officials in Ogden, 35 miles north of Salt Lake City, placed the entire town under a form of protective sequestration. All outsiders entering the town from a community where quarantine restrictions were not as strict as in Ogden would be required to present a certificate of good health issued not more than 24 hours prior. Special guards were placed at all the entrance points to the town to check for these certificates and to turn back those who did not possess them.37 Park City, approximately 15 miles southeast of Salt Lake City as the crow flies, barred everyone except soldiers from entering the town; incoming soldiers were placed in quarantine for 48 hours to ensure they were disease-free.38 In surrounding Salt Lake County, where a closure order was still in effect, county officials complained to the governor that the partial reopening of the city placed county residents at risk while also negatively impacting county business interests.39

The number of new cases continued to decline as Christmas approached, with most of them developing in households already under quarantine. Schools were scheduled to reopen on December 26, but that date soon was pushed back to December 30 to provide time for teachers and principals to finalize plans for making up lost instruction time. When they did reopen, an extra hour was added to the school day, taking grammar schools until 4:00 pm and high schools until 3:20 pm for the rest of the school year.40 Teachers were instructed to monitor students for symptoms of influenza and to send sick children home until a school nurse or health official cleared the patient to return to the classroom. Children were required to bring in a report on influenza cases–both past and present–in the household.41 The first day saw better than expected attendance at Salt Lake City schools, with rates as high as 90% in some schools. Officials attributed some of the absences in the high schools to students finding employment during the closure period.42

Salt Lake City continued to see handfuls of influenza cases develop throughout the rest of the winter, although never at the same levels experienced during the fall. Still, health authorities did not relax their guard. At least one physician, a Dr. Openshaw, was arrested for failure to report a case of influenza.43 Despite a significant drop-off of cases in February, the health department continued to quarantine houses each day, well into April. By the end of its epidemic, Salt Lake City experienced a total of 10,268 reported cases, nearly nine percent of its population. Of those who fell ill, 576 residents died as a result of influenza or pneumonia, a case fatality ratio of 5.6 percent.44

Notes

1 See, for example, “Blue Reports on Influenza,” Salt Lake Tribune, 14 Sept. 1918, 13, and “War Is Begun on Influenza,” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 Sept. 1918, 13.

2 “Influenza Is Readily Prevented, Says Paul,” Salt Lake Tribune, 27 Sept. 1918, 11.

3 “Preparing Here for Spanish Influenza,” Salt Lake Tribune, 4 Oct. 1918, 20.

4 “Disease Appears in Utah Centers,” Salt Lake Tribune, 5 Oct. 1918, 1.

5 “Influenza Claims 63 New Cases Here,” Salt Lake Tribune, 9 Oct. 1918, 16.

6 “Drastic Action Is Taken by Officials,” Salt Lake Tribune, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 “Drastic Action Is Taken by Officials,” Salt Lake Tribune, 10, Oct. 1918, 1.

8 “Hurry Work on Preparing Hospital for Emergency Use,” Salt Lake Tribune, 10 Oct. 1918, 11.

9 “Fifty Towns in Grip of Influenza,” Salt Lake Tribune, 13 Oct. 1918, 24.

10 “Fort Douglas Is Now Quarantined,” Salt Lake Tribune, 17 Oct. 1918, 14.

11 “Influenza Takes Still Firmer Grip,” Salt Lake Tribune, 18 Oct. 1918, 14.

12 “Influenza Spreading in Salt Lake City,” Salt Lake Tribune, 19 Oct. 1918, 14.

13 “Disease at Apex, Doctors Declare,” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 Oct. 1918, 24. On the evening of October 21, Beatty announced that “Spanish influenza in Utah is checked for the time being,” basing his assessment on the stable number of new influenza cases reported to his office from communities across the state for the previous two days. See “Disease Is Checked, Dr. Beatty Reports,” Salt Lake Tribune, 22, Oct. 1918, 16.

14 “Dread Influenza Still Grips Utah, Salt Lake Tribune, 23 Oct. 1918, 14. One hundred and eleven new cases were reported in the city on October 23, and similar numbers were reported for subsequent days. See, for example, “Wearing of Masks Made Mandatory,” Salt Lake Tribune, 26 Oct. 1918, 16.

15 “Wearing of Masks Made Mandatory,” Salt Lake Tribune, 26 Oct. 1918, 16.

16 “Influenza Increases Here; State Improving,” Salt Lake Tribune, 28 Oct. 1918, 1.

17 “Influenza Situation Given at a Glance,” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 Oct. 1918, 16.

18 “Homes of Victims to Be Placarded,” Salt Lake Tribune, 30 Oct. 1918, 16.

19 “Influenza Ravages Show Slow but Steady Decrease,” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 Oct. 1918, 16.

20 “Influenza Now Reported Waning,” Salt Lake Tribune, 8 Nov. 1918, 9.

21 “Influenza Under Control Locally,” Salt Lake Tribune, 11 Nov. 1918, 14.

22 “Four Deaths are Influenza’s Toll,” Salt Lake Tribune, 12 Nov. 1918, 16.

23 “Defer Action on Reopening Order,” Salt Lake Tribune, 13 Nov. 1918, 4.

24 “Lifting of Ban Is Still in Abeyance,” Salt Lake Tribune, 15 Nov. 1918, 15.

25 “Enforced Vacation Worries Teachers,” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 Nov. 1918, 16.

26 “Plan to Put End to Epidemic Here,” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 Nov. 1918, 16.

27 “Plan Drastic Step to Conquer ‘Flu,’” Salt Lake Tribune, 21 Nov. 1918, 8.

28 ‘Flu’ Closing Ban Starting in City,” Salt Lake Tribune, 22 Nov. 1918, 14.

29 “’Flu’ Mask Issue up to Board of Health,” Salt Lake Tribune, 30 Nov. 1918, 1.

30 “Dr. Beatty Makes Plain His Position of Mask Question,” Salt Lake Tribune, 30 Nov. 1918, 9. The Salt Lake County commissioners did, however, make mask use compulsory

31 “Open Inoculation Stations to Stem Progress of ‘Flu,’” Salt Lake Tribune, 1 Dec. 1918, 24. The Leary formula was developed by Dr. Timothy Leary, a bacteriologist at Tufts College Medical School in Boston, using three strains of influenza bacilli. See Timothy Leary, “The Use of Influenza Vaccine in the Present Epidemic,” American Journal of Public Health 8(10):754-755,768.

32 For example, on December 5 alone, 1, 365 residents received their free vaccination, and 67 houses were quarantined, and only one influenza death was reported. See, “But One Flu Death Reported Thursday,” Salt Lake Tribune, 6 Dec. 1918, 16.

33 “Salt Lake Churches Will open Tomorrow,” Salt Lake Tribune, 7 Dec. 1918, 1.

34 “Influenza Rules Will Be Rigidly Enforced,” Salt Lake Tribune, 8 Dec. 1918, 1.

35 “Board Protests School Closing,” Salt Lake Tribune, 11 Dec. 1918, 2.

36 “Exclude All Children from Theaters,” Salt Lake Tribune, 12 Dec. 1918, 9.

37 “Ogden Takes Steps to Restrict Entry; Drastic Rule Made,” Salt Lake Tribune, 8 Dec. 1918, 19.

38 “Decrease in New Flu Cases Noted,” Salt Lake Tribune, 9 Dec. 1918, 12.

39 “New ‘Flu’ Cases Drop to Fifty-Nine,” Salt Lake Tribune, 10 Dec. 1918, 12.

40 “City Schools open on Monday Morning,” Salt Lake Tribune, 24 Dec. 1918, 16.

41 “Teachers Meet for Institute Work,” Salt Lake Tribune, 28 Dec. 1918, 4.

42 “City Schools Open; Attendance Large,” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 Dec. 1918, 5.

43 “Forty-Nine ‘Flu’ Cases Reported in Town,” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 Jan. 1919, 16.

44 “Flu in February Shows Big Decline,” Salt Lake Tribune, 1 March 1919, 16.

Click on image for gallery.

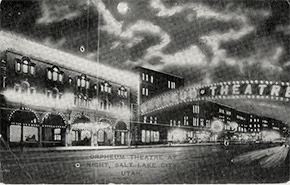

The Capitol Theatre (part of the Orpheum chain) at 50 W. 200 S. Street at night, illuminated by hundreds of light bulbs. The Italian Renaissance building was constructed in 1912 and still stands today. The theater was closed – along with all of Salt Lake City's other places of public amusement – for two months during the influenza epidemic.

Click on image for gallery.

The Capitol Theatre (part of the Orpheum chain) at 50 W. 200 S. Street at night, illuminated by hundreds of light bulbs. The Italian Renaissance building was constructed in 1912 and still stands today. The theater was closed – along with all of Salt Lake City's other places of public amusement – for two months during the influenza epidemic.