Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

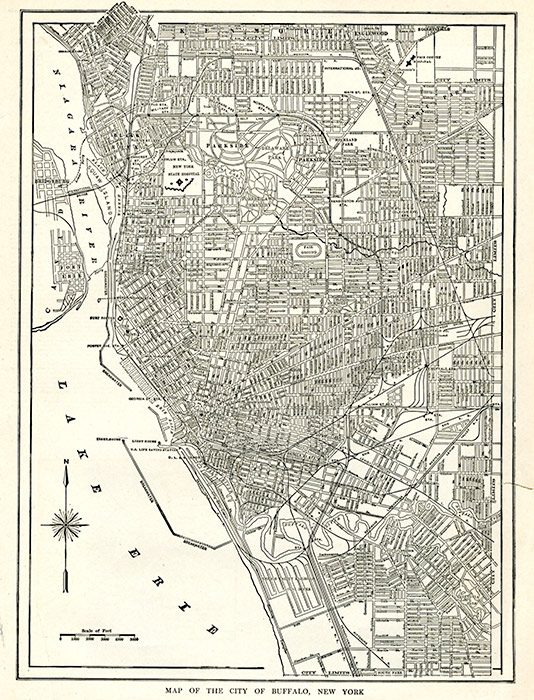

Buffalo, New York

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

On September 20, with reports of an influenza epidemic raging at the nearby Niagara-on-the-Lake military facility and news of the disease’s spread throughout the Northeast, Buffalo’s Acting Health Commissioner Dr. Franklin C. Gram (appointed in April when Health Commissioner Dr. Francis Fronczak was commissioned in the Army) asked city physicians to report to the Health Department any and all cases of influenza they encountered. Health Commissioner Gram’s goal was not only to get accurate statistics on the disease in his city, but also to isolate and quarantine all cases and contacts. Thus far, there were no official reports of influenza in Buffalo, but the Health Commissioner expected that to change shortly. He told the public that influenza was a serious disease, and that symptoms should not be dismissed even if mild. To drive the point home, he called influenza a disease as contagious as measles, a malady with which most families had more familiarity.1 Ten days later, Buffalo physicians had reported fifty cases in the city.2 Gram braced himself for the onslaught he knew was coming.

On October 7, as Buffalo’s epidemic began accelerating, city officials created a special sub-committee to lead the anti-influenza campaign. The committee included Health Commissioner Gram, Mayor George Buck, Chief of Police Henry Girvin, Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce George Lehman, and City Council President Henry D. Miles, and met with representatives from the school system, Fort Porter, the Buffalo Medical Society, industrial plants, retail shops, theaters, and movie houses. Together, the group decided that a sweeping closure order might be necessary in the coming days if Buffalo’s influenza situation did not improve drastically. Theater and movie house owners, not surprisingly, suggested that their venues be kept open and used for “preventative propaganda” to educate the public. A representative of Buffalo’s school system stated that schools would close only in a case of extreme necessity, but likewise offered the schools as places from which to disseminate public health information. To help limit the spread of influenza, the sub-committee recommended to the city council that outsiders be barred from attending public gatherings in Buffalo. For the time being, however, Buffalo residents were free to go about their lives uninterrupted.3

That freedom did not last long. On October 10, acting on the strong recommendation of Health Commissioner Gram and under emergency authority granted him by the city council, Mayor Buck ordered closed all schools, churches, saloons, movie houses and theaters, pool halls, five-and-ten stores (quickly removed from the list after owners protested), ice cream parlors and soda shops, and barred all indoor gatherings and meetings of any sort effective at 5:00 am the next morning.4 Buffalo’s streetcar strike precluded the need for the ventilation or passenger restrictions used in other cities. The Health Department divided the city into 21 separate districts, each with its own health inspector in charge of enforcing the order. The move came just as Buffalo was experiencing a sharp rise in new cases; nearly 700 were reported the day Mayor Buck issued the order, more than double the figure for the previous day. Residents ill with influenza were told they had to remain in their homes under isolation. Non-ill family members, however, were free to come and go as they pleased. The hope was that these measures would bring the epidemic under control and forestall the need to extend the order to include industrial plants and commercial businesses.5

Movie house and theater owners, knowing that box office returns would be down until the epidemic was brought under control, supported the closure order. Saloons owners and brewers, on the other hand, protested, claiming that saloons did not tend to draw large crowds and that the closure order would put them out of business. Health Commissioner Gram deftly responded by cutting off their main source of complaint. “I am going to appeal to your manhood and not to your pocketbooks,” he told the liquor interest, “because I know that if it came to losing a member of your family by death or your money you would give up every dollar to save life.” Saloons and brewers immediately agreed to support the closure order.6

Several other groups balked at the order as well, and sought special dispensations from the Health Department. Christian Science churches requested exemption from the closure order, which Health Commissioner Gram promptly declined. Similarly, the Erie County Medical Society asked that, as physicians, they still be allowed to hold their regular meetings. Gram rejected this request as well, stating that doctors would be given no special privileges. Medical society members could still meet, however, at the October 12 conference on influenza control in Buffalo’s factories, where all city physicians were welcome. As for Christian Scientists, technically they were still allowed to hold open-air services, as nearly every other city church and synagogue had planned for the upcoming weekend, despite Gram’s recommendation that they not. In the end, however, Buffalo’s clergy heeded the Health Commissioner’s warning and canceled their outdoor services.7

Meanwhile, Buffalo’s epidemic had grown severe. Over 1,700 new cases were reported on the first day of the closure order, with 53 new deaths. Casket makers could not keep up with demand; their usual capacity was thirty per day, but the number of epidemic deaths alone far surpassed that. Hospitals similarly were overwhelmed with patients and in desperate need for physicians and nurses. Gram did his best to alleviate the situation. He ordered the department of sanitation to begin producing caskets. These would be sold to families that could afford them and given to the poor for free. He sent word to the adjutant general at Albany asking that physicians serving on state draft boards be sent to Buffalo to help. He asked city physicians to volunteer to care for patients free of charge and to be reimbursed by the Health Department. He requested Red Cross nurses serving at Fort Niagara return to Buffalo, and for all retired and practical nurses to lend their services. The old Central High School building was quickly converted into a 1,000-bed emergency hospital. Last but not least, Gram announced that no one exposed to influenza or showing symptoms of the disease would be allowed to leave Buffalo or to enter the city from outside, especially from Canada. Along with recommending that residents use influenza masks while in public and enforcing the closure order, it was all Gram could do.8

Over the course of the next two weeks, Buffalo’s epidemic crested, with over 22,000 cases and nearly 1,800 deaths reported for October.9 But the city was finally on the road to recovery. By the end of the month, new case tallies began to drop. On October 28, Gram announced that he was anxious to lift the closure order and gathering ban, but would wait to see how the how the end of streetcar strike and the resumption of service would affect the epidemic.10 After waiting a few days to make sure that the epidemic would not spike again, Mayor Buck issued a proclamation to rescind Buffalo’s closure orders effective at 5:00 am on Friday, November 1. Schools remained closed until Wednesday, November 6 in order to give teachers–many of whom had volunteered for the city’s door-to-door influenza canvassing efforts–a few days break and to disinfect and ventilate classrooms.11

On November 3, the influenza advisory panel officially declared that Buffalo’s epidemic had ended. For the first time since the start of the crisis, Municipal and City hospitals were clear of influenza and pneumonia cases, having moved their patients to the Central High emergency hospital.12 Some argued for keeping Central High as an emergency hospital even after the last of the influenza victims had convalesced and been discharged. Opponents noted that the building was located between two sets of streetcar tracks, making it a rather noisy and unpleasant place to recuperate. Besides, the building was owned by the Board of Education, not the Health Department, and was needed for schooling Buffalo’s teenagers. Even Gram, who had advocated for its use as an emergency hospital, believed that the Central High building better served the city as a school than as a health care facility.13 After reviewing the situation and considering the future needs of Buffalo, the city council decided to allow Central High to return to duty as a school building when the last of the influenza patients had recovered.14

By the time Thanksgiving rolled around, Buffalo was in the clear, despite new influenza cases still being reported each day. December, however, saw a small surge in the epidemic, with as many as 138 new cases being reported on a single day (December 21).15 The situation continued to grow more severe by mid-January, when upwards of 300 new cases per day were being reported by city physicians.16 Suddenly, Health Commissioner Gram fell ill. Immediately his temporary replacement, Dr. George Staniland, ordered the clerk in charge of calling in the daily influenza case tallies to the newspapers to stop doing so; from now on, newspapers would have to call the Health Department for that information. Staniland claimed the reason for the change in policy was because the case numbers were so low that it would be of “no use to ask you [newspapers] to publish them any longer.” The Secretary of the Board of Health had a different take: Staniland did not want to panic the public with the spike in cases, and so ordered that the daily count not be revealed until after 11:00 pm, when the morning edition papers went to press.17

Over the course of the next few weeks, the epidemic subsided completely and life in Buffalo returned to normal. The epidemic had been costly, both in lives and in dollars. The city spent approximately $75,000 in its battle with influenza, most of which went to hospital patient care. Between the start of the epidemic in September 1918 and the end of the year, 28,398 official cases of influenza were reported in Buffalo. Of this, nine percent (some 2,561) died of pneumonia or other influenza complications.18 The total excess death rate attributed to the epidemic was 530 deaths per 100,000 people, a figure similar to that of other Eastern cities.

Notes

1 “City Girds Self to Fight Dread Spanish Grippe,” Buffalo Courier, 21 Sept. 1918, 5.

2 “Much Sickness in Buffalo Now Just Plain Grip,” Buffalo Courier, 30 Sept. 1918, 5.

3 “Spanish Flu Gaining Here, Officials Talk of Closing Schools, Theaters, Churches,” Buffalo Courier, 8 Oct. 1918, 4.

4 Annual Report of the Department of Health, Buffalo, NY, for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Buffalo: 1919), 19-21. The closure order and gathering ban were actually issued as two separate, back-to-back orders when it became clear that clarification and extension of the original closure order would be necessary to enforce further social distancing measures.

5 “City Closes Today to Fight Influenza which is Spreading,” Buffalo Courier, 11 Oct. 1918, 1; “1,237 New Flu Cases; Close More Places; Urge Masks on All,” Buffalo Courier, 12 Oct. 1918, 5.

6 “Proclamation,” Buffalo Courier, 11 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 “1,237 New Flu Cases; Close More Places; Urge Masks on All,” Buffalo Courier, 12 Oct. 1918, 5; “Church Plan Open-Air Services for Tomorrow,” Buffalo Courier, 12 Oct. 1918, 4.

8 “1,726 New Cases, 53 Deaths in 24 Hours; Not Enough Doctors,” Buffalo Courier, 13 Oct. 1918, 43; “1,237 New Flu Cases; Close More Places; Urge Masks on All,” Buffalo Courier, 12 Oct. 1918, 5; “83 Die in Day; 1,717 New Cases,” Buffalo Courier, 17 Oct. 1918, 1.

9 “New Flu Cases Drop to 569 for Day; 1010 Deaths,” Buffalo Courier, 26 Oct. 1918, 5.

10 “Only 66 Deaths and 268 New Flu Cases Yesterday,” Buffalo Courier, 28 Oct. 1918, 4.

11 “Buffalo Free of Flu Ban Today,” Buffalo Courier, 1 Nov. 1918, 15.

12 “Committee Calls Flu Epidemic at End in Buffalo,” Buffalo Courier, 4 Nov. 1918, 5; “Remove All Flu Cases to Central High Hospital,” Buffalo Courier, 3 Nov. 1918, 5.

13 “Health Dept. Wants to Retain Old High School as Hospital,” Buffalo Courier, 21 Nov. 1918, 6; “Hartwell Opposes Using Old Central High as Hospital,” Buffalo Courier, 24 Nov. 1918, 53; “Dr. Gram Would Give up Hospital in ‘Old Central,’” Buffalo Courier, 25 Nov. 1918, 4.

14 “Old C.H.S. Returns to School Dept. at End of Flu Danger,” Buffalo Courier, 29 Nov. 1918, 4.

15 “Influenza Shows Increase; 138 New Cases in 24 Hours,” Buffalo Courier, 22 Dec. 1918, 3.

16 See, for example, “288 Flu Cases in 24 Hours, Record Since Epidemic,” Buffalo Courier, 14 Jan. 1919, 12; “Flu Jumps to 319 Cases in 24 Hours,” Buffalo Courier, 15 Jan. 1919, 12.

17 “128 New Flu Cases, 17 Deaths, in Day,” Buffalo Courier, 18 Jan. 1919, 10.

18 Annual Report of the Department of Health, Buffalo, NY, for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Buffalo: 1919), 18.