Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

On September 24, as the national press covered the escalating influenza epidemic on the East Coast, Dallas Health Officer Dr. A.W. Carnes warned his community to expect a visit soon from the rapidly spreading disease. Closer to home, some 700 cases of influenza were reported to exist among the soldiers at Camp Logan, near Houston. Conditions at the camp were so bad that medical personnel had to erect temporary emergency hospitals to care for patients. Several other Texas locations reported small numbers of cases as well, as did Camp Bowie outside of nearby Fort Worth. Carnes was not overly concerned with the news either from within his state or from the East, however, believing that this novel form of influenza was only slightly more severe than common grippe. He recommended that residents get plenty of fresh air, avoid crowds, and keep their bowels open, and asked anyone feeling ill to go home and rest. An opinion piece in the Dallas Morning News claimed that too much was being made of epidemic influenza. “A good many of our modern maladies seem to be the inventions of that pseudo-science which parades in the columns of the popular press,” the author wrote. These notions were about to be severely tested, as five Dallas civilians already were reported ill with influenza.1

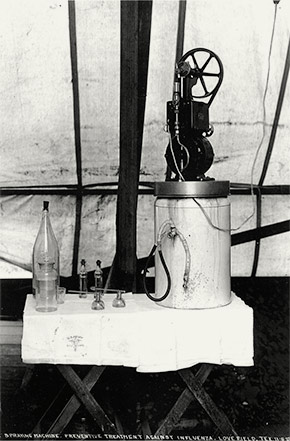

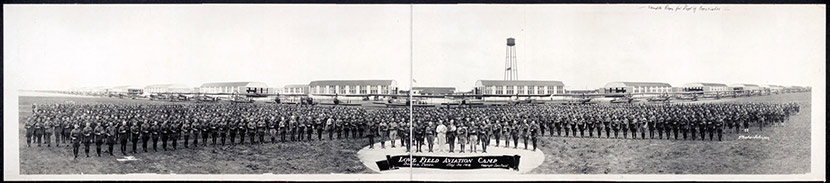

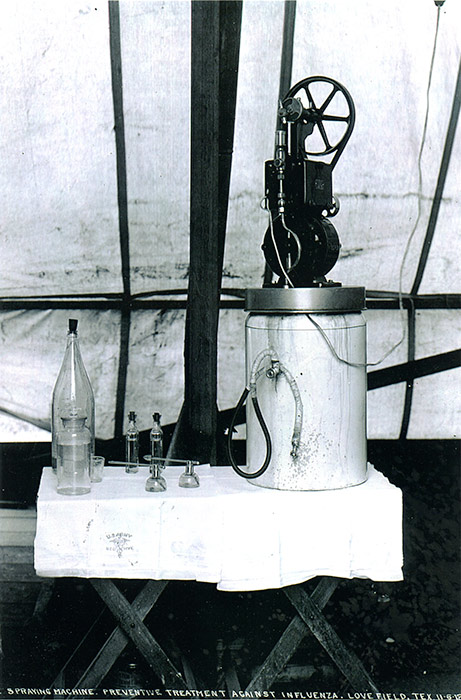

In an attempt to contain their epidemics and to safeguard their troops, medical officers at nearby military camps instituted protective measures. Camp John Dick Aviation Concentration Camp, a small holding facility located on the state fairgrounds in Dallas itself, had 20 cases of influenza. Camp surgeon Major Vernon C. Earthman ordered that all incoming men be placed in quarantine until it was clear that they were influenza-free.2 At Camp Bowie outside of Forth Worth, 40 miles west of Dallas, a camp-wide gathering ban kept soldiers from congregating at theaters, pool halls, or dances either on base or in Forth Worth.3 Love Field and the aviation repair depot in northwest Dallas were placed under quarantine as a precaution, although no cases of influenza were reported there. Those men leaving the post on official business were required to submit to physical inspection and have their throats sprayed with argyrol (an antiseptic originally developed to prevent gonorrheal blindness in newborns) upon their return.4

It was September 27. There were now at least 15 cases of influenza in Dallas, five of which had been admitted to Dallas Emergency Hospital. Influenza was not yet a reportable disease in the city, leading at least one doctor to estimate the real number of cases as four times as high. Carnes requested that physicians send him notice of all suspicious cases as quickly as possible. He also asked that physicians treat patients in their homes and not to send them to Parkland Hospital (then located at the corner of Oak Lawn and Maple) in order to protect the patients there. To augment the city’s healthcare, Carnes offered the services of visiting physicians from the health department. He still held firm to the belief that the burgeoning epidemic was nothing more than common grippe, but told reporters that he was prepared to issue strict disease control measures if necessary.5

Carnes hesitancy to take more vigorous action saved the upcoming Liberty Loan parade but allowed thousands to crowd Dallas’s downtown streets. On Saturday, September 28, patriotic throngs flocked to the business district to see 5,000 civilians and 2,500 enlisted men march in the parade launching the Fourth Liberty Loan campaign. Singing “For Your Boy and My Boy,” the crowd overflowed one of the largest blocks in the city before marching down South Harwood Street. As one reporter described the scene, “It simply was Dallas showing what she intends to do when the loan drive opens tomorrow.”6 The gathering and ensuing hoopla was undoubtedly great for the loan campaign. It was also undoubtedly bad for the city’s health.

By October 3, Dallas had 119 influenza cases and one death, that of 15-year-old Pierpont Balderson, who died at St. Paul’s Hospital on September 30. Most physicians pegged the actual number of cases as much higher. Every sector of the city was hit.7 Hospitals began isolating their cases, and physicians at the Dallas Baby Camp, a charity hospital for children, preemptively closed its doors to visitors and the potential introduction of the rapidly spreading virus.8 Twenty Red Cross volunteers engaged in canteen work at the Union Terminal Station were out sick with influenza, greatly hindering the work. Carnes considered but decided against asking the City Commission to pass an emergency ordinance giving his health department the power to isolate all cases and quarantine suspected contacts, even though Mayor Joseph E. Lawther was eager that Carnes should begin such work. For the time being, Carnes simply recommended that the public refrain from patronizing businesses that maintained their establishments in an unsanitary condition.9

Carnes may not have been ready to act, but others certainly were. George W. Simmons, director of the Southwest Department of the Red Cross, hastily dispatched a telegram to the local Dallas chapter, asking it to mobilize its facilities and volunteers to help deal with the growing epidemic. The Dallas County Nurses’ Registry likewise began organizing units of undergraduate and practical nurses to combat influenza. Graduate nurses were in great demand but limited supply, and the Registry issued an appeal to retired and married nurses for assistance.10 Expecting more cases to develop, doctors at Parkland Hospital turned the basement chronic disease ward into an isolation ward and moved their 14 influenza patients there.11

Carnes momentarily reconsidered his position, and on October 4 asked Mayor Lawther to convene the city commission and to pass an ordinance making influenza a quarantineable disease. The next day, however, he postponed his request, believing that the situation did not yet demand such action. Carnes called Dallas’s situation “uncomfortable,” but far better than in most other places.12 Lawther was not quite so assured as his health commissioner. The mayor called a special meeting of the Board of Health for Wednesday, October 8 to discuss possible epidemic control methods, including the closing of Dallas’s schools as per Acting Governor Willard Johnson’s suggestion that communities consider such a move. He also called on residents to clean their homes, businesses, and communities. “Your failure to clean up might be the cause of your wife or your child becoming infected with this new plague which is daily claiming a toll of lives.” He told Dallasites. “Let us make Dallas the cleanest city in the country as a preventive measure.”13

When the Board of Health met, members were divided as to the best course of action to take. The Board agreed on the need to make influenza a reportable disease, and asked the city commission to pass such an emergency ordinance at its October 9 meeting. The Board asked Carnes immediately to issue a circular asking physicians to report all cases of influenza to his office, since, under Dallas law, emergency ordinances did not become effective for three days. It also directed Carnes to notify the public about the dangers of influenza, how to avoid the disease, and how best to treat it. As for more assertive methods of disease control, Board members were of split opinion. Dr. V. P. Armstrong, Assistant Health Officer, believed that Dallas’s epidemic was already far worse than being reported, and that the only way to bring it to a quit halt was to close all public places immediately. “This disease is spread through the breathing apparatus, and the thing to do is to close all of the schools, the moving picture shows, the churches–wherever people congregate, whether it be a dog fight or a prayer meeting,” he told his fellow Board members. His colleague, Dr. Crow, argued that it was not clear how the disease was spread, and that the situation was not nearly serious enough yet to take such drastic action. Most of the cases thus far were among adults, he added, thus negating the need for school closures.14 Crow ignored reports from Dallas’s three high school principals, stating that nearly twenty percent of the student body was absent.15

As cases mounted in Dallas’s schools, so did they in the city’s hospitals. There were 220 cases listed at Emergency Hospital, with another 200 cases and three deaths at St. Paul’s Sanitarium, a Catholic hospital that had given over many of its beds-including some in a temporary tent hospital erected on the front lawn-to military cases. Twenty-two cases were reported at the Baptist Memorial Sanitarium.16 The local chapter of the Red Cross called on any and all volunteer nurses it could to help deal with the growing epidemic; it was able to mobilize 135 graduate nurses, 20 undergraduate nurses, and 19 practical nurses for service in the county. None could be spared for other parts of Texas.17 The Dallas County Nurses’ Registry was receiving dozens of calls for help each day, many from nearby military camps, but had difficulty in finding nurses to fill them.18 To make matters worse, an outbreak of whooping cough among babies in South Dallas further added to the nursing shortage, as volunteers from the Infant’s Welfare and Milk Association cared for the afflicted babies while many of their parents tried to convalesce from influenza.19

Carnes slowly came around to the need for action. Meeting with leaders from St. Matthew’s Cathedral on October 9, the health commissioner advised against proceeding with the upcoming four-day festival scheduled to begin Sunday, October 13. The cathedral’s dean decided to postpone the festival until after the threat of the epidemic had passed.20 Later that day, Mayor Lawther, Carnes, the Board of Health, and 50 Dallas physicians met to discuss the ever-growing crisis. Over 330 cases of influenza had been reported that morning, bringing the total number in the city to over 1,000. Every Dallas hospital was overcrowded with influenza cases. At Parkland, recovering patients had to be moved into the hallways to make room for new arrivals. Carnes called the situation an “influenza invasion.” The Board decided that the time had come to ask Mayor Lawther to issue a citywide closure order and public gathering ban. The mayor agreed. Effective Thursday, October 10, all Dallas theaters, playhouses, and all other places of public amusement were to be closed. Those present were split as to the issue of schools, with the majority favoring keeping classrooms open so that children could spend their days in well-ventilated buildings where they could be monitored for illness rather than in dingy homes or on the city’s streets. The situation in the high schools had stabilized, and there was only a slight increase in the number of absences in the elementary schools. For the time being, therefore, Dallas’s children would continue to attend class. School authorities agreed with the decision, but instructed their teachers to send any and all sick children home immediately.21 As a further measure, Carnes requested that the Dallas Railway Company disinfect its streetcars daily, that they permit only as many passengers as seats, and that they put more cars into service during rush hour.22

Owners of affected businesses immediately grumbled over being singled-out. The directors of the Chamber of Commerce and representatives of the Manufacturers’ Association met with Carnes and several members of the Board of Health to discuss what they considered was an unfair closure order. Theaters, movie houses, and other like places were closed but schools were still allowed to remain open, they complained. Carnes countered that keeping the schools open was important to the safety of Dallas’s children. He added that if the schools were closed, there would still be plenty of reason to keep theaters and amusement houses–places with dim lights and often poor ventilation–closed. In fact, if schools were closed, Carnes reason, a compelling argument could be made to make the closure order even more sweeping. “If the schools are closed,” he told the businessmen, “then there would be just as much reason for closing the large stores, where hundreds of people work together and go in and out of their places of work solely by means of elevators. If the schools are closed the street cars should by all means be stopped.” Schools, he added, were far less likely to be places where influenza was spread. The Chamber of Commerce, met with opposition and without a quorum present, tabled the matter.23

Despite his argument, Carnes doubted the efficacy of any closure order, school or otherwise. Focusing not on the number of influenza cases–cases that were already overwhelming Dallas’s hospitals, nurses, and physicians–but on deaths, Carnes told the public that the disease mainly affected those in their 20s. That, he said, accounted for why influenza was such a problem in the military camps and cantonments. Nearly every military camp had implemented a quarantine, to little or no effect, he claimed. The real solution to the problem of influenza, according to Carnes, lay in the proper care of the patient so that complications did not develop.24 For Carnes, the epidemic itself could not be controlled, only the number of resultant deaths. It was a rather stunning and narrow-minded belief, one that disregarded the social and economic dislocation caused by the growing volume of influenza cases that were already taxing Dallas’s healthcare system and giving organizations such the Dallas County Nurses’ Registry fits. In fact, Carnes’ statement was not even factually correct: he claimed that the first death among the city’s children had been in a baby less than a year old, forgetting that Dallas’s first death had been 15-year-old Pierpont Balderson.

Mayor Lawther, however, was not so resolute. Although he had been willing to follow the advice of medical men thus far, residents were increasingly clamoring for greater action to stem the rising tide of disease. On the morning of Saturday, October 12, Lawther unilaterally closed all public and private schools, churches, and other public gatherings, against the advice of the Board of Health. “I am taking this action not because the situation in our city is alarming,” he told residents, “but as a measure of safety and precaution and because it seems to be the desire of our citizenship.” Lawther was sure to make clear that neither he nor health officials believed the epidemic was out of hand, nor did they expect it to soon become so. The case tallies, however, did not jibe with Lawther’s statement: 659 new cases for a total of 2,719 in the city were reported for the day.25

Despite the closure order, Lawther and Carnes still believed that promoting a thorough clean-up of Dallas was the best way to combat the rising number of influenza cases. The mayor appointed W. S. Lee, an executive officer of the Dallas chapter of the Boy Scouts, to take charge of the campaign, and to marshal the children to help. Playing on the heightened patriotism of a nation at war, Lawther told the city’s children that “If Dallas is not cleaned up, the influenza may continue, and if it continues, it is hurting our country just as much as the German bullets.”26 The president of the City Federation of Women’s Clubs joined the cause, asking Dallas’s women to clean their residences while imploring city officials to keep the streets free of debris and unsanitary food vendors.27

Fortunately, others concentrated more directly on dealing with the epidemic, now well on its way to a peak. The caseload at Emergency Hospital was overwhelming the staff there, and eight nurses were themselves sick with influenza and unable to care for patients. To help alleviate the problem, the health department contracted with a doctor to devote half of his time to influenza cases brought in by the city.28 Volunteers at the Dallas chapter of United Charities were hard at work caring for 100 destitute influenza victims, many of them from the same family. In one case, a father worked all day at his job and all night tending to his sick wife and children until he, too, contracted influenza. The larder was nearly empty, and the family had no money with which to pay a doctor or to buy medicine. The Humane Society was busy caring for 16 babies abandoned by parents too sick to care for them.29 The Dallas County Nurses’ Registry was receiving calls for aid every minute, and its staff worked ceaselessly without rest. Registry director Alma Rembert said there was no use making more appeals for volunteers, as any and all Dallas women with nursing experience were either already engaged in such work or were unable to do so.30 At the Buckner Orphans’ Home, 200 of the 500 children and two nurses were sick with influenza; the nine teachers there cared for the ill.31 Institutional racism and the widespread prejudice of the times compounded Dallas’s healthcare problem. So few nurses were willing to serve Dallas’s African American community that Carnes had to appoint a black nurse to the duty. Likewise, Cotilde Rivera was dispatched to care for city’s Mexican residents, many of whom were so poor that they did not have beds or bedding. Within a few days, she too fell ill with influenza.32

By the morning of October 22, the epidemic appeared to be dwindling, leading Carnes to optimistically announce that the closure order might be rescinded within a week. Dallas’s case data, such as it was, indicated that the epidemic had peaked on October 12, when a record 782 new cases were reported. When the day’s tallies arrived at Carnes’s office, however, they painted a different picture: 137 new cases were reported from Emergency Hospital alone. Carnes recanted his previous statement, telling the public that the gathering ban and closure order would continue. He added that residents should not worry about influenza, as it would weaken one’s immunity to the disease.33

For the next week the daily number of new cases reported by Dallas hospitals and physicians fluctuated, frustrating Carnes as well as Dallasites eager to see their city return to its normal functioning. Carnes blamed the stubbornness of the epidemic on careless residents who refused to stay indoors during the city’s recent spate of cool, wet weather.34 Church leaders, in particular, were tiring of the closure order; a group of pastors petitioned Mayor Lawther to allow regular services to resume on Sunday, October 27. People will gather anyway, they argued, and at least open churches would give them a well-ventilated place to congregate. It was also good for the preservation of morale, they said, doubly important during such trying times. Lawther refused the petition.35 Several churches opted to hold outdoor meetings–as they had the Sunday previous–since the closure order only banned indoor services.36

Finally, on the evening of Thursday, October 31, after meeting with health officials who gave their assent, Lawther announced the step-wise lifting of the closure orders. With extremely short notice, schools reopened the next morning so that students could receive assignments. To appease clergy, Lawther gave special permission to the city’s Catholic and Episcopal churches to hold All Saints’ Day services. Then, on Saturday, November 2, Dallas’s places of amusement reopened for business.37 Dallasites flocked downtown to have fun. “The city is alive with enthusiasm and prosperity is reflected on every side,” one reporter wrote of the scene. Some went shopping to be among the crowds, while others went to The Old Mill to see Douglass Fairbanks in He Comes Up Smiling or Harold Lockwood–who had died of influenza in New York only two weeks earlier–in Pals First at the Queen.38

Over the next two weeks, the number of new cases dropped to levels low enough to prompt Carnes to recommend that the ordinance requiring physicians to report influenza cases be rescinded. The City Commission did so on Friday, November 15, essentially marking the end of Dallas’s epidemic. Over 9,000 cases of influenza had been reported to-date, with nearly 250 deaths.39 The disease threatened to make a strong comeback in early-December, prompting Mayor Lawther to threaten the public with a second closure order and gathering ban unless residents were more cautious. The City Commission reinstated the reporting ordinance on December 9 and considered issuing another closure order but, along with Lawther, deferred action while Carnes was in Chicago for the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association. Schools were particularly hard-hit: more than 2,500 students and 47 teachers were absent on account of influenza. Fortunately, cases appeared to be milder than they had been in October, although an additional 80-odd deaths had already been added to the list.40

In the end, no second closure order was implemented. Carnes returned from Chicago on December 14 and shared with his colleagues the knowledge he had gained while there: proper rest and personal hygiene and care were the best courses of action.41 Within a few days, the number of influenza cases had dropped low enough to make the issue moot.42 Dallas’s epidemic had finally come to an end.

It is difficult to ascertain the severity of Dallas’s epidemic. Beginning on September 27, Carnes requested that physicians report influenza cases, but the ensuing ordinance did not become law until October 12, leaving a significant gap for which case reporting was not mandatory. We will never know how many cases slipped through the proverbial cracks during this lag. In addition, most health departments devoted significant space to the influenza epidemic in their 1918 annual reports, providing detailed analyses of the timeline of the epidemic, the number of cases each month (or even each week, for some cities), and the like. Dallas’s, however, has nary a word on the epidemic. In fact, health officers were immensely more interested in smallpox, malaria, typhoid fever, and impure food and milk than they were with influenza and the destruction it wrought. The only information provided is the total number of lobar pneumonia and influenza deaths for the period between May 1918 and May 1919: 813 in all, equaling a death rate for those diseases of 511 per 100,000.43

Contemporary newspaper reports provided slightly better, if still problematic, figures. On December 13, before the end of the epidemic, the Dallas Morning News reported that 456 residents had died from influenza or pneumonia since October 1, giving Dallas an enviable epidemic death rate of approximately 286 per 100,000.44 Two days later, the Morning News printed a story summarizing reports from the American Public Health Association annual meeting in Chicago, in which Dallas was said to have an epidemic death rate of about 250 per 100,000.45

Despite the variation in the figures, it is clear then that Dallas fared better than most American cities at the time. With an epidemic death rate of somewhere between 250 and 511 per 100,000–and most likely closer to the lower figure–Dallas weathered its epidemic better than most other Southern cities (New Orleans: 734/100,000; Birmingham: 592/100,000) and even better than most Midwestern communities, the region that tended to have the best outcome.

Notes

1 “Expects Spanish Influenza to Be Common,” Dallas Morning News, 24 Sept. 1918, 7; “Spanish Influenza Reported in Texas,” Dallas Evening Journal, 25 Sept. 1918, 2; “40 Influenza Cases Now at Camp Bowie,” Dallas Morning News, 27 Sept. 1918, 9; “Fourteen Pages,” Dallas Morning News, 27 Sept. 1918, 8; “To Avoid Spanish Influenza, Which is Like La Grippe,” Dallas Morning News, 26 Sept. 1918, 7.

2 “Local Army Posts Guard against Influenza,” Dallas Morning News, 27 Sept. 1918, 13.

3 “40 Influenza Cases Now at Camp Bowie,” Dallas Morning News, 27 Sept. 1918, 9.

4 “Local Camps Guard against Influenza,” Dallas Morning News, 28 Sept. 1918, 7.

5 “Quarantine Placed on Love Field to Prevent Influenza,” Dallas Evening Journal, 27 Sept. 1918, 10.

6 “Liberty Loan Parade Marked by Patriotism,” Dallas Morning News, 29 Sept. 1918, 9.

7 “Big Increase in Influenza Cases Here; Report 119,” Dallas Evening Journal, 3 Oct 1918, 1;“Spanish Influenza Rapidly Increasing,” Dallas Morning News, 4 Oct. 1918, 14.

8 “Establish quarantine at Dallas Baby Camp,” Dallas Evening Journal, 3 Oct. 1918, 2.

9 “Big Improvement in Epidemic of Influenza Here,” Dallas Evening Journal, 4 Oct. 1918, 4.

10 “Local Red Cross to Assist in Influenza Epidemic,” Dallas Morning News, 4 Oct. 1918, 6.

11 “Influenza Cases Here total 327; Three Have Died,” Dallas Evening Journal, 5 Oct. 1918, 1.

12 “Spanish Influenza Rapidly Increasing,” Dallas Morning News, 4 Oct. 1918, 14; “Influenza Situation Slightly Improving,” Dallas Morning News, 5 Oct. 1918, 6.

13 Mayor Issues Call for Clean Premises,” Dallas Morning News, 8 Oct. 1918, 6.

14 “Seek to Have Doctors Report All Influenza,” Dallas Morning News, 9 Oct. 1918, 3.

15 “453 Children in Three High Schools out from Sickness,” Dallas Evening Journal, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

16 “220 New Cases of Influenza Reported Here Wednesday,” Dallas Evening Journal, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

17 “Red Cross Here Unable to Help Outside Places,” Dallas Evening Journal, 9 Oct. 1918, 9.

18 “Unable to Fill All Calls for Nurses,” Dallas Morning News, 10 Oct. 1918, 6.

19 “Whooping Cough Adds to Influenza Woes among Babies,” Dallas Evening Journal, 9 Oct. 1918, 10.

20 “St. Matthew’s Festival Will Not Be Held,” Dallas Evening Journal, 9 Oct. 1918, 9.

21 “Big Increase in Influenza Cases,” Dallas Morning News, 10 Oct. 1918, 16.

22 “Wants Street Cars Disinfected Every Night for Awhile,” Dallas Evening Journal, 10 Oct. 1019, 5.

23 “No Action Is Taken on Closing Schools,” Dallas Morning News, 11 Oct. 1918, 16.

24 “Statement Issued by Dr. Carnes as to Epidemic Here,” Dallas Evening Journal, 11 Oct. 1918, 7.

25 “City Schools and Churches Ordered Closed by Mayor,” Dallas Evening Journal, 12 Oct. 1918, 1.

26 “Cleaning Up of City Will Lift Quarantine,” Dallas Morning News, 15 Oct. 1918, 6.

27 “Clean-Up Campaign is Making Progress,” Dallas Morning News, 17 Oct. 1918, 13.

28 “City Engages Another Doctor for Emergency,” Dallas Evening Journal, 17 Oct. 1918, 5.

29 “Charity Donations Like Paying Taxes,” Dallas Morning News, 18 Oct. 1918, 8.

30 “Influenza Epidemic Brings Heavy Demand for Nurses,” Dallas Morning News, 19 Oct. 1918, 7.

31 “Fewer Influenza Deaths Reported,” Dallas Morning News, 23 Oct. 1918, 14.

32 “Decrease in Cases of Influenza Here,” Dallas Morning News, 21 Oct. 1918, 10; “Poor Suffering from Influenza; Charities Helping,” Dallas Evening Journal, 23 Oct. 1918, 6; “Increase Is Shown in Influenza Cases,” Dallas Morning News, 26 Oct. 1918, 14.

33 “Quarantine Likely to Last Another Week,” Dallas Morning News, 22 Oct. 1918, 14; “Sharp Increase in Influenza Cases; Deaths Decrease, Dallas Evening Journal, 22 Oct. 1918, 1.

34 “Influenza Cases Still Increasing,” Dallas Morning News, 27 Oct. 1918, 5.

35 “Increase Is Shown in Influenza Cases,” Dallas Morning News, 26 Oct. 1918, 14.

36 “Influenza Ban Not to be Lifted for Several Days,” Dallas Evening Journal, 26 Oct. 1918, 3.; “Pastors Send Messages to Members of Churches,” Dallas Morning News, 19 Oct. 1918, 17.

37 “The Quarantine Off,” Dallas Evening Journal, 1 Nov. 1918, 6; “Episcopal and Catholic Churches to Hold Services,” Dallas Morning News, 1 Nov. 1918, 6.

38 “Public Ready for Early Holiday Buying,” Dallas Morning News, 2 Nov. 1918, 18.

39 “More Than 9,000 Influenza Cases, with 350 Deaths,” Dallas Evening Journal, 15 Nov. 1918, 1.

40 “Influenza Causes 332 Deaths Here, Carnes Reports,” Dallas Evening Journal, 5 Dec. 1918, 1; “Influenza Cases Must Be Reported to Health Board,” Dallas Evening Journal, 9 Dec. 1918, 1; “More Than 2,500 Children Sick and Out of Schools,” Dallas Morning News, 11 Dec. 1918, 15.

41 “Health Officers Not Favoring Quarantine,” Dallas Morning News, 15 Dec. 1918, 7.

42 “40 Influenza Cases Reported Thursday,” Dallas Evening Journal, 19 Dec. 1918, 1. Dallas newspapers reported declining numbers of new cases in the ensuing days.

43 See City of Dallas, Department of Public Health, Summary Report of Activities for the Year Ending April 30, 1919 (Dallas, 1919).

44 “Preventive Measures Against Influenza Urged in Letters,” Dallas Morning News, 13 Dec. 1918, 4.

45 “Health Officers Not Favoring Quarantine,” Dallas Morning News, 15 Dec. 1918, 7.