Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Los Angeles, California

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

It was mid-September 1918 when cases of influenza began appearing in the Los Angeles area. At first, the disease attacked seamen aboard a naval vessel that had arrived in the harbor. On September 28, officials at the Naval Reserve Station at Los Angeles Harbor was placed their installation under quarantine, although they were quick to state that the move was merely precautionary, as no cases yet existed. Several days later, Army officials placed the Arcadia Balloon School under protective quarantine, prohibiting the men there from visiting nearby Pasadena and other communities without special permission. There too, officials stated that there were no cases amongst soldiers.1

The first civilian cases in Los Angeles appeared on September 22, although influenza was not made a reportable disease in California until September 27.2 Amongst these first cases were 55 students at Polytechnic High School, at the time located on the corner of Washington Boulevard and Flower Street in downtown. Publicly, City Health Commissioner Dr. Luther Milton Powers only described the Polytechnic cases as “alleged influenza.”3 Privately, he took stock of resources and advised Mayor Frederic Thomas Woodman that the city should prepare an active campaign to limit or control the influenza epidemic that was just starting to develop. Mayor Woodman responded by appointing 11 of the most respected Los Angeles physicians, plus Dr. E. A. Ingham, the California Health Department’s Los Angeles representative, to form a Medical Advisory Board to support Health Commissioner Powers.4 When the new advisors met on October 10, businessmen and various state, county, and local health officers, including those from Pasadena, Long Beach and other adjacent cities, joined them. Paving the way for immediate municipal action, the group recommended closing schools, theaters, churches, dance halls, and other public meeting places, as well as daily disinfection for all public transportation vehicles.5

The next day, on October 11, Mayor Woodman declared a state of public emergency.6 The City Council confirmed the health department’s legal right to issue a closing order and passed an ordinance giving Powers authority to act in the emergency. The health commissioner then ordered schools closed and banned all public gatherings – including public funerals, movie houses, theaters, pool rooms, and other public entertainments – effective 6 p.m. the same day. The list of closed venues was more or less exactly what other local and state health officers across the United States also closed. Because of its burgeoning film industry, however, Los Angeles also had two novel bans: the filming of mob scenes was prohibited, as were any crowds that gathered to watch street scenes being filmed.7 One of the first victims of the gathering ban was the upcoming Liberty Day Parade. Liberty bond sales may have suffered a bit as a result, but Angelinos, fortunately, may have dodged a bullet.8 In other cities, tens of thousands gathered for the celebrations kicking off the Fourth Liberty Loan drive, creating conditions perfect for the spreading of influenza. In Los Angeles, however, residents had at least one less opportunity for getting sick.

Los Angeles prepared to do battle with influenza. As Angelinos adjusted to the restrictions, Powers’ Medical Advisory Board met regularly, modifying the rules of closure from time to time as dictated by necessity. Clarifying questions ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous: Are dental schools included in the ban? What about piano lessons? Should businesses stop holding sales, playing music or doing other things to attract crowds? Will the health department recommend wearing gauze masks? Should they be mandatory? Since poolrooms are closed, should a hotel shut down its single pool table?

Tracking the epidemic, the health department quickly began issuing daily statistics to show the number of reported new influenza and pneumonia cases and deaths. People watched for any sign that the epidemic was abating. For the three-day period ending October 14, only 300 cases and 11 deaths were recorded, leading Powers to opine – prematurely – that the epidemic may have peaked. He also expressed confidence in the city’s hospitals to manage emergency cases. In a well-timed show of support, the City Council had appropriated funds enabling the health department to hire more inspectors and to create at least one temporary hospital, the first of three to be assembled that fall.9 Five thousand dollars went to outfit an emergency hospital at the Parent-Teacher Clinic on Yale Street. The new hospital opened on October 19, as the number of new cases per day approached 800.10

Still, Powers wanted the City Council to appropriate more funds for patient care. When he declared that people in the harbor district needed an emergency hospital close to their homes, the City Council appropriated $4,800 for a 35-bed emergency hospital in the Women’s Club House in San Pedro. On October 19, Powers was back, asking City Council to fund three more part-time physicians to visit the sick. Council members supported Powers’ request.11 Then, in mid-November, Powers realized that many poor patients lacked a place to fully recover after being discharged from hospital. Once again, the City Council agreed to the emergency appropriation, this time to the tune of $10,500 used to convert a vacant hotel into a 100-bed convalescent hospital for the poor.12

To Mask or Not to Mask?

The value of gauze masks became a hotly debated issue in the Los Angeles medical community and in city chambers. Visiting medical experts, various health authorities, and even political figures voiced a variety of opinions about masks’ efficacy, confounding the ability of city leaders to reach a consensus. Woods Hutchinson, a physician and vocal proponent of gauze masks for influenza infection control, campaigned for their use in Bay Area cities. He found a receptive audience, and San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley all issued mandatory mask orders. On October 23, the Los Angeles Times ran a statement from California Governor William D. Stephens calling for voluntary mask wearing for all as a way of controlling the epidemic.13

From the Bay Area, Hutchinson made his way to Los Angeles to press his cause there. L.A. city leaders were not as easily convinced on the mask issue as their Northern California counterparts, however. Mayor Woodman felt that they might offer some protection and therefore should be used. Powers and members of the Influenza Advisory Committee agreed. The City Council, however, did not. After some discussion, the City Council simply decided to recommend masks except for situations where the state required their use, namely for anyone with cold or influenza symptoms, health professionals, and visitors and family members while in contact with influenza cases.14 Two weeks later, in an attempt to have the Council change its mind, Woodman sent gauze masks to each member in an effort to join them in the cause. Several refused to don them. Defeated in his gesture, Woodman and Powers simply reiterated the Council’s recommendation that people wear flu masks when in places of business, street cars, or when in direct communication with others.15 Two days later, United States Surgeon General Rupert Blue telegraphed Powers specifically asking him not to issue a mandatory mask order.16 The City Council, until then still entertaining the idea of issuing a mandatory mask order, decided against the move.17

The value of influenza vaccines was also debated energetically amongst those in the Los Angeles medical community. On October 25, the state Department of Public Health announced a statewide plan to provide inoculations to all Californians who wanted one. Periodically, the L.A. health department directed Angelinos to three sites in the city for free inoculations.18 The program was not very popular, however, and grew less so in late-November when one representative of the U.S. Surgeon General’s office told Los Angeles residents that he was not very enthusiastic about the efficacy of the vaccine.19

As October waned, the daily tally of new influenza cases fell below 1,000. Powers announced (again, prematurely) that the tide had turned in the fight against the epidemic, although he refused to speculate on when the ban on public gatherings might be lifted. On October 31, the City Council passed two new anti-influenza ordinances at Powers’ request: one requiring tenants of properties to clean their front doorways and sidewalks every morning, and the other creating an official “clean-up” week to disinfect all sections of the city.20 A week later, on November 6, City Council again responded favorably to Health Commissioner Powers’ request for more funding. This time, he and Settlement Association supervisor Ruth C. Hoffman, supported by the Los Angeles Rotary Club, requested $10,500 to convert the Mount Washington Hotel in the northeastern section of the city into a convalescent home for recovering influenza patients without the means to support themselves.21 City Council members also approved staggered business hours to reduce crowding on streetcars, effective on November 9. By then the daily tally of new cases fell below 800 for the first time in a month.22

City of Angels?

The struggle over the masking issue was not the only source of tension. In early-November, a group of Christian Science churches formulated plans to reopen despite the closure order. Church leaders questioned the constitutionality of shuttering churches. Police Chief John L. Butler responded by ordering his officers to arrest any and all worshippers attending services. The tactic failed to deter them. On November 3, the board of directors of the Ninth Church of Christ Scientist on South New Hampshire Street reopened their church. They were promptly arrested and taken to central booking. The whole move was designed to challenge the ordinance in a test case before the state Supreme Court.23 It did not go very far. The California Supreme Court in San Francisco refused to issue a writ of habeas corpus for the main defendant, Harry Hitchcock, stating that to do so would cast suspicion on the closure ordinance and thus make its enforcement difficult.24

Meanwhile, on November 7, the Theater Owners’ Association, with their president Frank McDonald in the lead, made a dramatic appearance at a City Council session. Each was wearing an influenza mask. In muffled tones, they respectfully told the Council there were other places of business that should be closed, too.25 Days later, the same group added more detail when it formally petitioned City Council to close all but essential businesses like grocery and drug stores, and make mask wearing mandatory. They reasoned that enacting more stringent social distancing measures would help stamp out influenza once and for all, quickly returning Los Angeles commercial activities to normal.26 Several City Council members agreed. Five of them said openly that theater owners were not being treated fairly. Ultimately, however, the Council was united in agreeing that decisions about emergency health measures rested with the health commissioner, and so they referred the matter to Powers. He did not see any practical way to enforce widespread closures and mandatory wearing of masks for the nearly 600,000 residents of the city, and so he denied the request.27

By mid-November, the number of new influenza cases dropped dramatically, but still hovered in the 500 per day range. The city appeared to be through the worst of the epidemic, although, with approximately 500 new cases reported each day, Los Angeles was not out of the woods quite yet. Powers optimistically predicted restrictions might be lifted in a week. In the meantime, Mayor Woodman voiced his support of Powers’ decision to deny the request of the Theater Owners Association to enact a wider closure order. With the Mayor backing Powers, theater owners brought their issue to motion picture producers from several of the largest studios in Southern California. Together, they appealed directly to the Influenza Advisory Committee, asking it to enact a strict five- to seven-day closure of nearly every public place in the city.28

The legal battle with Christian Scientists and now the attack from theater owners strained the relationship between Powers, the City Council, and the Advisory Committee. Council members were divided into two camps. Four reasoned that Powers and the Influenza Advisory Committee should be allowed to do their job without interference from business or religious interests. The other five were convinced that an aggressive and wider closure order was the best way to eliminate influenza.

The two camps clashed energetically. In fact, when the Evening Herald covered the November 15 City Council session, its article remarked on “considerable bitterness and wrangling” among Council members on the issue of closing the city in response to the theater owners. But in a vote of seven to two, they finally adopted a resolution calling on Powers to close the city for five days, with the understanding that the ban on public gatherings would be lifted entirely at the end.29 Powers was defiant and refused to enforce the resolution. On November 16, after confirming with the City Attorney that emergency ordinances required the unanimous vote of the City Council, he challenged its members to issue a stricter order themselves.30 Like a contagious disease, opinions about how to stamp out influenza spread throughout business community; two merchants’ associations disagreed with the theater owners and vigorously protested against a total closure before City Council.31

The uproar gave Mayor Woodman a chance to exercise his skills of arbitration. On November 18, he assembled the Influenza Advisory Committee, Powers and Frank MacDonald, president of the Theater Owners’ Association in order to resolved the issue. Against the backdrop of diminishing influenza cases, the Advisory Committee announced an end to the influenza ban as of 6:00 am on November 21. Powers, they said, would ask City Council to repeal the current closing ordinance.32

Despite the good news, bickering broke out again, this time between the Mayor and City Council over which, exactly, had the authority to lift the ban – Health Commissioner Powers or City Council. While city government hung in limbo, Powers detected a sudden, serious increase in the number of influenza cases. After meeting with the Mayor, Police Chief, and City Attorney, Powers announced he was postponing cancellation of the ban. Predictably, this angered the Theater Owners’ Association, which continued to advocate closing the city.33 In a rather feeble attempt to mollify angry theater owners, the Influenza Advisory Committee asked Angelinos to participate in a voluntary “Stay At Home Week.” Few residents complied, and the request fell flat.34

The bans stayed in place. For the rest of November, as theater owners and dry goods representatives continued hounding City Council, its sessions grew increasingly dramatic, with name-calling and some theater owners storming out in protest. In disgust, Mayor Woodman issued a public statement explaining that he was powerless to act, and that California law was insufficient to permit the health commissioner to fully control the situation.35

Land of Sunshine

Although City Council could not agree on closing the city entirely, it eventually was able to agree on when to reopen the city. On November 29, the number of new reported influenza cases fell below 350. Health Commissioner Powers and the Influenza Advisory Committee asked City Council members to pass an ordinance lifting the ban effective Monday, December 2 and to include provisions for the mandatory home isolation of influenza and pneumonia cases. 36 The Council voted unanimously to lift the closure order.37

Alas, Angelinos did not enjoy their return to normalcy for long, as the epidemic was not yet truly over. Alarmed by the upward trend in new cases, especially among children, Powers alerted the Board of Education and recommended that it consider closing schools.38 The Board agreed, and on December 10 ordered all public schools closed until further notice. City Council quickly passed the quarantine law Powers proposed in late-November and gave him every authority to enforce it.39 Now, municipal resources focused on quarantine as the most effective weapon against influenza. For the rest of the epidemic, the City Council appropriated money as needed to give the health department enough quarantine inspectors to visit homes, manufacturing plants, stores, hotels, and apartment houses. These temporary inspectors, many of whom were returning veterans, also ran errands for the sick and ministered to the needs of affected families.40

Mayor Woodman acted decisively to avoid conflict between the Los Angeles’s business interests and City Council. Within two days of the school closure announcement, the Mayor invited ten business and civic representatives to serve on a Business Advisory Committee.41 At its inaugural meeting on December 12, with Mayor Woodman and Powers present, no one dared to suggest another ban on public gatherings. Instead, the group focused on enforcing the quarantine and encouraging people to voluntarily wear influenza masks.42

The business advisors launched a publicity campaign to educate citizens on how to avoid infection. This included “four-minute” speakers – modeled on the Four Minute Men of the wartime Committee on Public Information campaign – who spread into the community at various public gatherings to talk about precautions. The advisors also hired a public relations expert to work with Powers on the campaign.43 City Council, relieved that business interests were staying away from its chambers, unanimously appropriated $35,000 to fight influenza. This lavish funding went to hiring more quarantine inspectors and to ramp up the public education campaign. The campaign theme: public health regulations were expensive, but personal action and caution was free.44

School Closures

Although the good working relationships among Health Commissioner Powers, Mayor Woodman, and Police Chief Butler helped to make management of the Los Angeles’s needs run smoothly, the rapport between Powers and the city school system was also praiseworthy. The October 11 closing order, which included schools, received full support from the Board of Education and Superintendent Albert J. Shiels. When, in December, Powers recommended they be closed again, Shiels and the Board quickly responded.45 The Board of Education kept schools closed well into the New Year.

In the meantime, Shiels implemented a system of correspondence instruction for the 90,000 children in the Los Angeles public school system and arranged for its 3,400 teachers to continue receiving their pay by either doing volunteer work or furthering their own education.46 At the end of the year, Shiels and Powers developed a system to monitor infection rates within the school district. Using this data, Powers was able to determine which areas were ‘flu free,” allowing schools in those neighborhoods to reopen. He also worked with the Board of Education to have physicians inspect students and teachers as each school prepared to open. As a result, the first five of the 230 public schools in Los Angeles reopened as early as January 9. As the epidemic subsided across the city, children once again returned to their classrooms. On February 6, the last of the remaining buildings reopened. Under the new model, thousands of children thus were able to return to their classrooms much sooner than otherwise would have occurred.47

Conclusion

Los Angeles used early and consistent measures to reduce exposure to influenza during an extended confrontation with the disease. These included school closures, a ban on public gatherings, enforcement of home quarantines starting December 2, and the cooperation of most of its citizens throughout the epidemic. This undoubtedly contributed to the city’s rather successful campaign against influenza.

There were problems, however. The debate over the efficacy of gauze masks revealed some of the cracks in the city’s otherwise unified façade. Theater owners protested against what they believed to be unfair treatment. This occurred in several other American cities as well. In Los Angeles, however, theater owners escalated the battle by bringing in producers and film studios. Then there was the legal challenge from Christian Science churches and their desire to bring a test case to the California Supreme Court or, if necessary, the federal courts. To be sure, the sailing was not entirely smooth in Los Angeles in the fall of 1918.

Ultimately, however, quick action, a strong working relationships that health commissioner Powers had forged over his many years of service, and good cooperation with city officials and business and civic organizations helped keep Los Angeles’s anti-epidemic campaign on track. In the end, Los Angeles experienced a lower epidemic death rate than many other American cities: 494 deaths per 100,000 people. By contrast, San Francisco – which acted slowly and which relied heavily on the purported protection of gauze face masks to stop the spread of influenza – had an excess death rate of 673 per 100,000.48 Powers, Mayor Woodman, and the City Council could be proud of their efforts.

Notes

1 “Rain Kills All Spanish Flu Germs, Belief,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 27 Sept. 1918, 5; “Quarantine Harbor Camp,” Los Angeles Times, 29 Sept. 1918, 11; “Preventive Measures,” Los Angeles Times, 3 Oct. 1918, 14.

2 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 6.

3 “Report Cases Of Influenza,” Los Angeles Times, 9 Oct. 1918, 2.

4 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 6.

5 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 12; “L.A. Acts to Keep Out Influenza,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 10 Oct. 1918, 3.

6 “May Soon Lift Closing Order,” Los Angeles Times, 11 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 “Leaders Confer on Flu Mask Plan for City,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 24 Oct. 1918, 10.

8 “Fighting ‘Flu’ In Los Angeles,” Los Angeles Times, 13 Oct. 1918, 1.

9 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 12-13; “May Soon Lift Closing Order,” Los Angeles Times, 11 Oct. 1918, 1; “City Acts to Bar Influenza Spread,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 11 Oct. 1918, 10.

10 “Pest Epidemic In All States,” Los Angeles Times, 16 Oct. 1918, 2; Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 12-13.

11 “Early Rout of Spanish Influenza Predicted,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 19 Oct. 1918, 3; “Must Pay Your Taxes By Mail,” Los Angeles Times, 22 Oct. 1918, 2.

12 “To Mask Or Not To Mask,” Los Angeles Times, 7 Nov. 1918, 1, 3.

13 “Governor urges all to combat epidemic,” Los Angeles Times, 23 Oct. 1918, 15.

14 “Urge Greater Efforts as ‘Flu’ Proves Stubborn,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 25 Oct. 1918, 3; “Experts Doubt Mask’s Value,” Los Angeles Times, 26 Oct. 1918, 1.

15 “Masked Men To Front Voters,” Los Angeles Times, 5 Nov. 1918, 4.

16 “Care Urged On ‘Flu’ Victims,” Los Angeles Times, 6 Nov. 1918, 2.

17 “Flu Fight May Stop Crowding of Cars,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 8 Nov. 1918, 3.

18 “Flu Still Decreasing,” Los Angeles Times, 2 Nov. 1918, 1.

19 “Stay At Home; Shop By Phone,” Los Angeles Times, 26 Nov. 1918, 1, 2.

20 “City Council Plans New ‘Flu’ Law,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 31 Oct. 1918, 3.

21 “To Establish Influenza Hospital For City,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 6 Nov. 1918, 3.

22 “Influenza Declining Rapidly Here,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 9 Nov. 1918, 3.

23 “Defy Fly Rule; Arrested,” Los Angeles Times, 4 Nov. 1918, 1.

24 “Scientist Churches Closed Tomorrow,” Los Angeles Times, 9 Nov. 1918, 1.

25 “Urge Tighter Lid,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 7 Nov. 1918, 9.

26 “Influenza on Steady Drop,” Los Angeles Times, 10 Nov. 1918, 6.

27 “Offer Mask Proposal,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 12 Nov. 1918, 4.

28 “Influenza In Continued Decline Here,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 14 Nov. 1918, 3.

29 Archives, City of Los Angeles. Letter from City Clerk to Health Commissioner, Nov. 16, 1918; “Council Asks Drastic Flu Ban; Now Up To Powers,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 15 Nov. 1918, 3.

30 “Hope To Lift Influenza Ban In L.A. Wednesday,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 16 Nov. 1918, 3; “Will Not Close City Up,” Los Angeles Times, 16 Nov. 1918, 1.

31 “May Lift Flu Ban This Week,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Nov. 1818, 7; “Powers Says Flu Danger About Past,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 18 Nov. 1918, 3.

32 “Flu Ban Off Thursday,” Los Angeles Times, 19 Nov. 1918, 1.

33 “Ban Off Again; On Again,” Los Angeles Times, 21 Nov. 1918, 1.

34 “Asks People To Stay Home,” Los Angeles Times, 25 Nov. 1918, 1.

35 “Stay At Home; Shop By Phone,” 26 Nov. 1918, 1, 2.

36 Resolution adopted by influenza advisory committee, 29 Nov. 1918, Los Angeles City Archives, Los Angeles, California; “1463 Fewer Cases this Week than Last,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 30 Nov. 1918, 1.

37 “Unanimous Decision Removes ‘Lid’,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 2 Dec. 1918, 3.

38 “Order Schools Closed Again,” Los Angeles Times, 11 Dec. 1918, 1.

39 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 13.

40 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 64.

41 Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 12.

42 “Influenza Is Reduced By Individual Quarantine,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 12 Dec. 1918, 3; “To Quarantine All Suspects,” Los Angeles Times, 12 Dec. 1918, 1.

43 “To Help Crush Flu Epidemic,” Los Angeles Times, 13 Dec. 1918, 1, 7.

44 “Money’s Voted To Fight Flu,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Dec. 1918, 10; Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Los Angeles, California, for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (Los Angeles, 1919), 63.

45 “Order Schools Closed Again,” Los Angeles Times, 11 Dec. 1918, 1.

46 “City School Pupils To Study By Mail,” Los Angeles Times, 13 Dec. 1918, 1.

47 “All Schools To Open In City Tomorrow,” Los Angeles Evening Herald, 5 Feb. 1919, 9.

48 Markel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA, et al. Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by U.S. cities during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA. 2007;298:647.

Click on image for gallery.

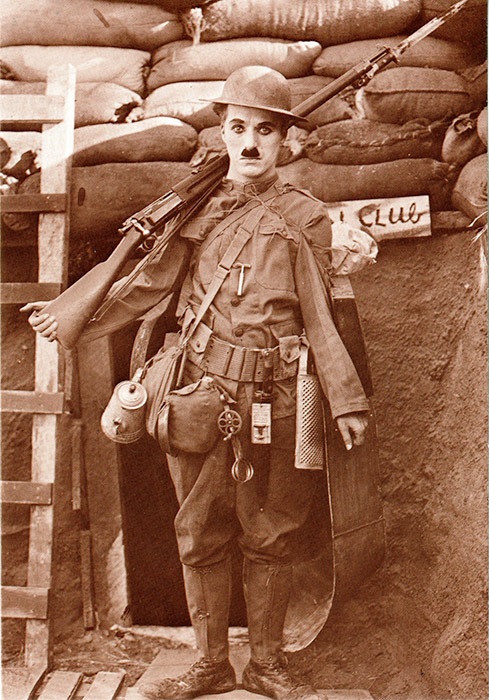

Douglas Fairbanks holding Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford on his shoulders in Hollywood. During the epidemic, each star had two films in release. In many cities, moviegoers had to wait until closure orders were lifted in order to see Fairbanks, Chaplin, and Pickford on the silver screen.

Click on image for gallery.

Douglas Fairbanks holding Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford on his shoulders in Hollywood. During the epidemic, each star had two films in release. In many cities, moviegoers had to wait until closure orders were lifted in order to see Fairbanks, Chaplin, and Pickford on the silver screen.