Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

New Orleans, Louisiana

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

On September 16, an oil tanker arrived at the port in New Orleans. On board were five crewmembers ill with influenza. Another crewmember, the ship’s radio operated, was said to have died of pneumonia while at sea. City health inspectors visited the ship and, upon discovering the ill men, immediately quarantined the vessel in the river across from the immigration station. The Board of Health then barred the ship from setting sail or coming to port until all the cases were cured.1 Two days later, influenza aboard the ship had spread to five more members of the crew. The ill men were removed from the tanker and brought to the Belvedere Hospital. The ship was then allowed to travel upriver to nearby Destrehan to unload its oil.2 Influenza was now in New Orleans.

The next day, September 19, the United Fruit Company cargo ship Metaphan arrived at New Orleans laden with bananas from Colón, Panama. On board were fifty civilians 86 crew, and fifty soldiers, 11 of whom had contracted influenza. The ill soldiers were removed to a post hospital at Jackson Barracks in the city’s Lower 9th Ward. The President of the Louisiana Board of Health, Dr. Oscar Dowling, immediately quarantined the ship for 48 hours while New Orleans Superintendent of Health Dr. William H. Robin took throat cultures from all aboard to check for influenza. The next day, authorities allowed the ship to unload its cargo so long as all aboard remained on the ship. Meanwhile, the state Board of Health hastily drafted an emergency amendment to the Louisiana sanitary code, mandating that physicians report cases of influenza to their local health boards as a wartime exigency.3

On September 29, New Orleans newspapers reported the city’s first local influenza death. Anticipating an epidemic, the nursing division of the New Orleans chapter of the American Red Cross nursing division began planning ways to meet the threat. Seventy-five trained nurses met to mobilize nursing units and to organize volunteers.4 Meanwhile, influenza cases began to mount. On October 2, a steamer with 56 infected men arrived at the naval station in the Algiers section of New Orleans. The sick men were sent to an isolated building at the Belvedere Sanitarium; the naval station already had over 150 cases and could not treat any more. Charity Hospital had several influenza cases – eight of them from yet another steamer that arrived at port – and the SATC infirmary at Sophie Newcomb College had 32 sick cadets under its care.5

By the end of the first week of October, it was clear that New Orleans’s influenza situation was growing rapidly out of hand. Due to lax compliance with the state order to report cases, however, local officials could not be sure just how many cases were in New Orleans. In addition, irregular reporting made it impossible to track the epidemic’s trend. On October 7, the New Orleans Board of Health made influenza a mandatory reportable disease, echoing the state Board’s earlier decision. In the state health offices, Dowling believed there were at least 7,000 active cases in New Orleans and decided that it was time to take action. That afternoon, he issued a circular to all local health officers across Louisiana, urging them to consider closing places of public gathering. He also suggested that they extinguish the streetlights at night to discourage people from gathering in the sidewalks, and that they limit the maximum number of passengers allowed on streetcars and maintain full ventilation.6

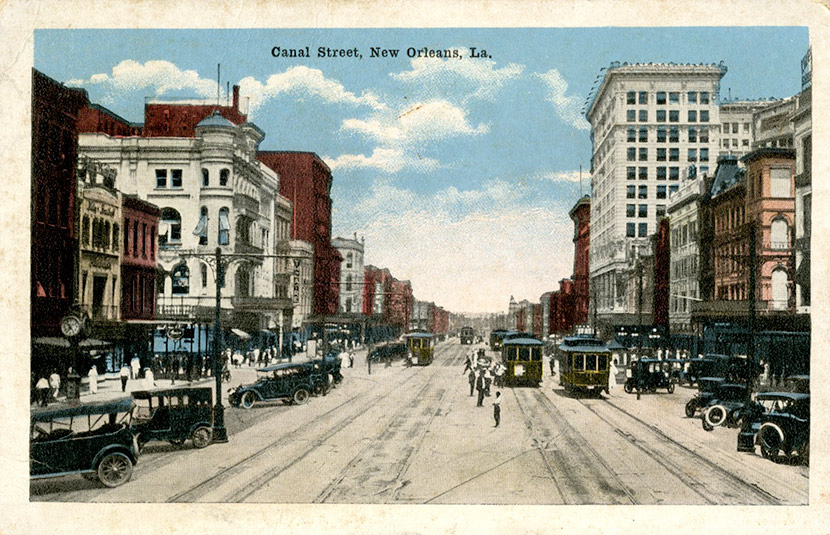

Robin and the New Orleans Board of Health acted immediately. The next day, October 9, with Mayor Martine Behrman’s consent and the blessing of state authorities, the Robin ordered closed all schools (public, private, and parochial, as well as commercial colleges), churches, theaters, movie houses, and other places of amusement, and to prohibit public gatherings such as sporting events and public funerals and weddings. Saloons, soda and ice cream parlors, and restaurants, however, were allowed to continue operating. Dowling, who had only recommended closure orders in his previous circular, now issued his own blanket closure order for the entire state.7 Several days later, on October 12, Dr. Robin instructed the New Orleans Railway and Light Company to ensure that no more than one passenger standing for every two passengers sitting would be allowed on the city’s streetcars. The transit company agreed to cooperate, as did the motormen’s union, which urged workers to disregard their usual nine-hour workday and make as many extra trips as required to keep streetcars from becoming crowded.8

As physicians – and households, as now required by city ordinance – began reporting cases more regularly, it became clear just how dire New Orleans’ epidemic situation really was. In just the two days of October 12 and 13, a total of 4,875 cases were reported to Robin’s office.9 Hospitals were overwhelmed with influenza and pneumonia cases. At the behest of United States Surgeon General Rupert Blue, local U.S. Public Health Service representative Dr. Gustave M. Corput worked to secure additional hospital space for those in service at adjacent naval and military installations. Within days, Charity Hospital reported that 17 wards – the entire second and third floors – now were devoted to influenza care.1 Amidst this alarming escalation of the epidemic, Mayor Behrman asked Surgeon General Blue to appoint Corput as medical advisor to New Orleans health authorities. Blue promptly did so, effectively giving Corput supreme command of the city’s anti-influenza campaign. Corput, already involved in looking for hospital beds for the military, expanded his work with the Red Cross to ensure sufficient emergency hospital facilities, staffing, and supplies for civilians as well.11

The Crescent City Pitches In

Corput and the Red Cross turned their attention to the Sophie Gumbel building on the Touro-Shakespeare almshouse property, an ideal candidate for conversion to a 300-bed emergency hospital. Since the city health department did not employ nurses, the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense and the Red Cross worked together to recruit nurses as well as physicians for the emergency facility.12 In coming days, the Red Cross emerged as the central clearinghouse for visiting and hospital nurses volunteering their services. Five hundred nurses answered its call in the first days of the epidemic.13 Additionally, Red Cross nurses visited the homes of hospitalized influenza patients to check the status of the other family members and to arrange for services when needed.14

Plans to ready the Gumbel emergency hospital hit a snag when health officials looked to the state and the United States Public Health Service to cover the costs for staffing, equipment, and facility renovations. In a leap of faith, the Red Cross continued to direct plant upgrades, including plumbing, wiring, and the purchasing of 300 beds and related supplies. When state officials baulked at financing the conversion, Corput and the USPHS agreed to assume responsibility for staffing expenses while the Red Cross covered the $30,000 price tag for renovations and supplies.15 Meanwhile, the Red Cross also readied smaller emergency facilities at the Southern Yacht Club on Lake Ponchartrain and at the Knights of Columbus hall in Algiers for military cases.16

Unfortunately, these new facilities were not nearly enough. Over 2,000 influenza cases were reported on October 20, the day the Gumbel emergency hospital opened, and subsequent days only saw an increase in that number.17 More help was necessary. Rising to the occasion, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks established a free dispensary to provide medication and food to the poor and organized 18 physicians to provide their services.18 By October 27, doctors working at the Elks lodge made close to 12,000 medical visits.19 The Moose fraternal lodge did its part too, donating its hall as a temporary emergency hospital.20 Albert Workman, president of the black-only Provident Sanitarium, offered his facility’s forty beds for the treatment of New Orleans’ African American influenza cases.21

At Tulane University, scientists developed and produced a vaccine for local use, knowing that such vaccines were unproven but believing that it was worth a try. Others agreed, and soon laboratories at area hospitals began manufacturing the Tulane vaccine in order to keep up with demand, as more than 4,000 city government employees and factory workers participated in voluntary vaccination clinics.22 Medical and nursing students at the university were deployed in New Orleans and throughout Louisiana. Third-year nursing students staffed the Gumbel emergency hospital while third- and fourth-year medical students took assignments across the state and at the Elks hospital and dispensary. At Corput’s request and with Tulane President Dr. Albert Dinwiddie’s approval, Surgeon General Blue appointed fourth-year medical students as assistant United States Public Health Service surgeons.23 Across the city, charitable and civic organizations pitched in to help New Orleans through the crisis.

On the Mend

As October drew to an end, it appeared as if New Orleans’ epidemic might soon be over. On October 25, city physicians reported 1,592 new cases of influenza, a large number to be sure, but one that represented a significant drop in the usual tally. In fact, it was the lowest number of new cases reported since the start of the epidemic.24 The trend continued the next day, when doctors reported 1,474 cases. Robin proclaimed that the crest of the epidemic had been reached, and although he cautioned residents to remain vigilant, he was hopeful that the disease would continue its downward trend.25 Nurses and doctors at the city’s hospitals and emergency facilities reported the same. At the Elks’ dispensary, volunteers filled fewer prescriptions and saw less demand for Red Cross nurses. Employers also reported that their workforce was beginning to return to full strength.26

On Friday, October 29, Corput, Robin, and Dowling met to discuss the possibility of allowing churches to reopen. Dowling ruled that churches across the state could reopen effective Sunday, December 1, provided ushers turned away those who tried to enter after pews were already full. Dowling gave local authorities power to reclose places of worship if they felt it necessary, although he urged them to do so after consulting him.27 A week later, on November 6, the triumvirate met once again, this time with twenty Louisiana physicians. Corput recommended lifting all remaining bans across the state in mid-November. After some discussion, the group set Friday, November 16 as the date, with schools to reopen the following Monday. Later that afternoon, Robin issued a proclamation approving this date for New Orleans, though the city ban on public wakes and funerals remained intact for a time.28

Some residents could not wait that long. On November 11, against a backdrop of a wildly celebratory Armistice Day, Louisiana’s War Finance Brigade – which handled New Orleans’s Liberty Loan drives – announced that it would meet daily at New Orleans’ Hotel Grunewald [known as the Roosevelt Fairmont today], despite the fact that public gatherings were still banned for five more days. Acting Governor Fernand Mouton baked this act of defiance, telling Liberty Loan workers that they would not face arrest if they disobeyed Dowling.29 With the closure order due to expire soon, Dowling, Corput, and Robin simply let the matter rest. On November 18, with New Orleans’s business and schools once again back to their normal operations, Corput declared the epidemic over.30

New Orleans was not entirely in the clear, however. In early December, the city experienced a slight increase in the number of new influenza cases being reported by physicians. The uptick lasted throughout the winter of 1919, with as many as 524 cases being reported at its height on January 14. New Orleans experienced so many cases that Charity Hospital officials turned their facility completely over to the care of influenza victims.31 Even Dowling himself fell ill with the disease.32 Unwilling to issue another sweeping closure order, however, and believing that it would be futile to selectively close some places while allowing the public to congregate in others, Dowling simply let the disease run its course. By early-February, the number of new influenza cases in New Orleans finally had slowed to a trickle.33

In New Orleans, Robin and Corput agreed the situation wasn’t alarming and affirmed that existing institutions were amply sufficient to provide care. New Orleans did handle the uptick quite well, and Robin declared this bout with influenza over on February 7.

Conclusion

The story of New Orleans’ battle with influenza is a particularly interesting one. A port city, it saw influenza arrive by sea via merchants and sailors. Three men – Robin, Corput, and Dowling – each played an important role in the epidemic response, working at the local, state, and federal levels to coordinate aid and services and implement public health measures. Despite the many opportunities for rancor amongst them, the group appeared to work together well for the most part. Moreover, the cooperation amongst and between charitable and civic organizations was unparalleled. These groups pitched in rapidly to establish additional emergency facilities, provide medications, prepare and deliver food and milk, and afford needed services to the stricken. Still, New Orleans’s epidemic was a devastating one. Between October 1918 and April 1919, the city experienced a staggering 54,089 cases of influenza. Of these, 3,489 died – a case fatality rate of 6.5%, and an excess death rate of 734 per 100,000.34 Only Pittsburgh (806) and Philadelphia (748) - the two cities with the worst epidemics in the nation – had higher death rates.

Notes

1 “No Danger of Spanish Influenza Epidemic Here,” New Orleans States, 16 Sept. 1918, 10.

2 “Influenza Patients Removed from Steamer,” New Orleans States, 19 Sept. 1918, 14.

3 “Ship Quarantined, Influenza Feared,” New Orleans States, 20 Sept. 1918, 7; “Fruit Steamer with Influenza Aboard Arrives,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 21 Sept. 1918, 5.

4 “Influenza Goes in Orleans Home to Get Victim,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 29 Sept. 1918, B8.

5 “Influenza Strikes Vessel’s Crew Hard,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 3 Oct. 1918, 8; “Think Influenza Crisis Now Past,” New Orleans States, 2 Oct. 1918, 3.

6 “Schools Closed; Churches Also Will Suspend,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 “All Shows, Churches Are Ordered Closed to Fight Epidemic,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 10 Oct. 1918, 1.

8 “Official Order Stops Crowding on Street Cars,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 13 Oct. 1918, 1.

9 “Influenza Gains while Hospital Plan is Rushed,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 12 Oct. 1918, 1; “Official Order Stops Crowding on Street Cars,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 13 Oct. 1918, 1.

10 “Influenza Crowds out Chronic Cases,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 10 Oct. 1918, 15.

11 “Dr. Baer Flu Cure Given to Public by Him,” New Orleans States, 12 Oct. 1918, 1, 2.

12 “Influenza Forces City to Provide Large Hospital,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 11 Oct. 1918, 1.

13 “Red Cross Nurses Handled epidemic Calls by Hundred,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 10 Nov. 1918, 14.

14 “1,946 new cases of flu in Orleans,” New Orleans States, 15 Oct. 1918, 6.

15 “New Emergency Hospital Ready for Sufferers,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 20 Oct. 1918, 4.

16 “Convalescent Enlisted Men at Yacht Club,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 21 Oct. 1918, 10; “Dr. Oscar Dowling, President of the State Board of Health, Hopes to See Decline in State’s Sick,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 23 Oct. 1918, 1.

17 “Influenza Makes Gaines and New Treatment Used,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 20 Oct. 1918, 1. Two days later, 2,783 cases were reported. Officials prematurely believed that the peak had been reached. See, “Report of Cases Shows Influenza is Abating,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 22 Oct. 1918, 1.

18 “Elks Issue Call for More Autos to Aid Sufferers,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 19 Oct. 1918, 3; “Elks Are Doing Splendid Work for the Needy,” New Orleans Times- Picayune, 21 Oct. 1918, 10.

19 “Doctors’ reports show conditions are much better,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 31 Oct. 1918, 1.

20 “Flu Cases Show Rapid Decline,” New Orleans States, 29 Oct. 1918, 4.

21 “2,318 New Cases of Flu Reported,” New Orleans States, 23 Oct. 1918, 5.

22 “Conditions here and over state are much better,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 26 Oct. 1918, 1.

23 “Emergency Hospital Treats 75 Patients,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 22 Oct. 1918, 1; “Health Reports from over State are Encouraging,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 19 Oct. 1918, 1; “Elks Extend Aid to Many Victims of the Epidemic,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 20 Oct. 1918, 4.

24 “Flu Conditions Much Improved,” New Orleans States, 26 Oct. 1918, 8.

25 “Flu Epidemic on Steady Decline,” New Orleans States, 27 Oct. 1918, 2.

26 “Disease Waning in New Orleans, But Not in State,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 25 Oct. 1918, 1; “Wane of Disease Seen, But Battle Must Not Relax,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 27 Oct. 1918, 1.

27 “Regular Services at All Churches to Begin Sunday,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 30 Oct. 1918, 1; “Churches Here Will Open Sunday,” New Orleans State, 29 Oct. 1918, 1.

28 “Nov. 16 Day Fixed for Raising ban against Crowds,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 7 Nov. 1918, 1.

29 “Acting Governor Orders Meetings to be Continued,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 12 Nov. 1918, 1.

30 “Influenza Beaten States Dr. G.M. Corput; Asks for Relief,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 18 Nov. 1918, 3.

31 “Charity Hospital Gives Influenza Victims Place,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 16 Jan. 1919, 3.

32 “”Physicians Called to Plan Checking Influenza Gains,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 14 Jan. 1919, 7.

33 “Flu Is Almost Wiped Out Here,” New Orleans States, 7 Feb. 1919, 13.

34 Biennial Report of the Board of Health for the Parish of Orleans and the City of New Orleans, 1918-1919(New Orleans: Brandao Printing Co., 1919), 8.