Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Syracuse, New York

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

“If we Syracusans are selfish enough to ask for a year-round camp here, we will have to put up with this condition all the time during the fall and winter.” Thus spoke Dr. Dwight H. Murray of the city’s Crouse-Irving Hospital on September 21, 1918. The condition to which he referred was influenza, which had recently attacked the Syracuse Recruit Camp and had put several hundred sick soldiers into city hospitals. Murray was not the only one exceedingly unconcerned with the sudden rise of influenza cases. Other hospital physicians simply chalked it up to “a combination of germs” resulting from the mixing of soldiers and recruits from across the country. Even city health officials seemed rather blasé about it, with one doctor calling it the same old-fashioned grippe that Syracuse residents had been dealing with for the past several decades.1

Within a few days the number of cases in Syracuse’s hospitals jumped even higher. Most of the hospitalized were soldiers, but civilian cases were on the rise as well. Hospital staff was already working round-the-clock to care for the sick, and the epidemic had only just begun. Bed space was at a premium; the Crouse-Irving Hospital crammed 300 influenza cases into a ward designed to handle only 200 patients. To help alleviate some of the pressure, hospitals converted specialized wards into influenza treatment areas. A shortage of nurses led to a call by the Red Cross for all graduate nurses in the area to assist in the fight against influenza. The commandant of the Recruit Camp detailed orderlies to work at the city’s hospitals, where they were assigned duties in the kitchens, laundry facilities, and in some cases even the wards. Syracuse threw all the resources it could muster against the rising tide of the epidemic, with little apparent effect.2

The situation continued to deteriorate rapidly over the next several days. Finally, on September 28, Lieutenant Colonel B. G. Ruttencutter, commander of the Syracuse Recruit Camp, ordered the camp under quarantine.3 Soldiers were now prohibited from leaving the camp and mingling with civilians, and civilians were likewise barred from entering from camp. It is likely that the quarantine had little if any effect on Syracuse’s epidemic, however. By this time, hundreds of sick soldiers were being cared for in civilian hospitals, and countless more soldiers had mixed with city residents. In fact, civilian cases were now on the rise as military cases at the recruit camp were declining.4

On October 4, after discussing the epidemic situation with Syracuse Health Officer Dr. David M. Totman and Commissioner of Public Safety Walter W. Nicholson, Mayor Walter R. Stone requested that city physicians report all civilian cases of influenza to the Health Department. It was only a request, however. As Health Officer Totman stated, “Influenza is not a reportable disease, and it is too late now to issue a regulation requiring that it be reported.” Instead, officials would rely on the cooperation of doctors in order to obtain accurate case data.5 The next day, 22 of Syracuse’s 170-odd physicians reported a total of 724 new cases. Totman estimated that, at that rate, the city had approximately 5,000 total cases of influenza. Mayor Stone took solace in the fact that this number did not seem proportionately higher than in other American cities, and he therefore did not see the need to issue a closure order at this time.6 For now, Syracuse waited, hoping the worst had passed.

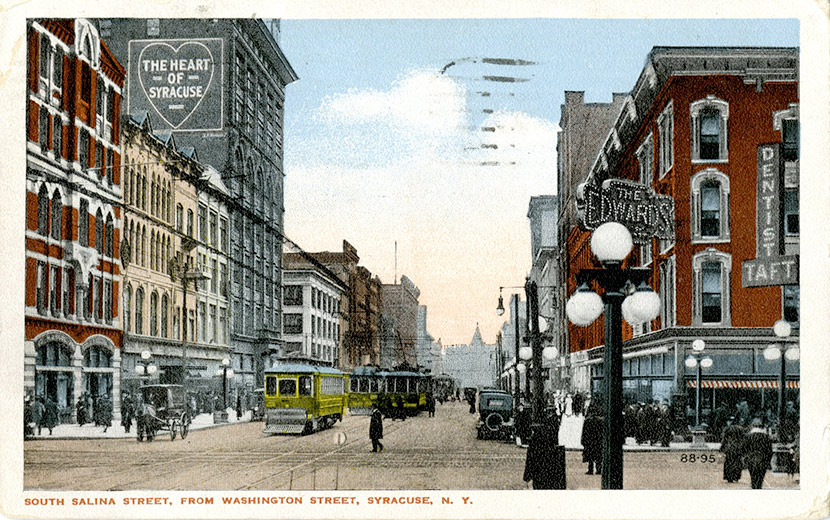

Only two days later, on October 7, as cases continued to mount, Mayor Stone ordered all schools, churches, theaters, dance halls, skating rinks, and other public places closed, and barred all public meetings, funerals, and other gatherings. The trustees of the city library system closed all library buildings. Parents were encouraged to have their children play outside but to prevent them from congregating in groups. School medical inspectors were released to work in their private practices, and school nurses were asked to carry out visitation work for the health department. No formal isolation or quarantine orders were issued, but residents were instructed to remain at home without visitors if they fell ill. Lastly, streetcars were to be fumigated daily, and restaurant sanitary conditions would be closely monitored by health inspectors.7 Mayor Stone asked the New York State Railways, an affiliation of several urban and interurban streetcar companies across the upstate region, to ensure that cars were not overcrowded. The company responded that, on the contrary, the epidemic had caused a drastic drop-off in ridership.8

To help the anti-influenza effort, Syracuse University suspended all large classes and requested that faculty and students stay away from the city’s business district. Cadets in the Student Army Training Corps were only allowed off campus with a special pass.9 Even the Boy Scouts had their activities curtailed when Safety Commissioner Nicholson ordered them to stop the door-to-door distribution of Liberty Loan literature and selling of war savings stamps.10

Syracuse’s hospitals struggled to accommodate the increasing number of patients, prompting officials to announce the opening of City Hospital to influenza cases provided enough nurses could be found to staff the facility. Health Officer Totman did not yet know where additional nurses could be found, as nearly every community across New York was being hard hit by the epidemic. The American Red Cross, Visiting Nurses Association, and even the United States Employment Service were doing their best to put out the call for trained nurses and volunteers, but demand outpaced supply.11

By mid-October, it appeared that the tide had turned. Physicians still reported large numbers of cases, but the daily tallies were declining. The local chapter of the Visiting Nurses Association reported a similar trend. Mayor Stone and Totman were cautiously optimistic that the closure order and gathering ban could be removed within a week’s time, provided the epidemic situation continued to improve.12 However, Totman was having difficulty obtaining accurate case data from physicians, despite influenza being made a mandatory reportable disease by the New York Board of Health (effective October 12).13 Not all physicians were reporting new cases in a timely manner, and the state health department pressured Totman to rectify the situation. Totman responded by reminding Syracuse’s doctors of their legal obligation to report cases and notified them that he would report any physician who was remiss. As a result, it was temporarily unclear whether the epidemic situation was improving, worsening, or stable.14 Totman believed that, at the very least, the existing evidence did not point to a substantial enough improvement to warrant lifting the closure order and gathering ban.15

Within a few days, however, as reports of lower case numbers continued to file into the health department, Totman and Mayor Stone began to believe that indeed the worst had passed. On Wednesday, October 23, after meeting with Totman and Stone, Safety Commissioner Nicholson announced the removal of the gathering ban effective 6:00 am Friday, October 25. Schools would reopen on Monday, October 28, where each of the city’s 25,000 schoolchildren would be monitored closely for signs and symptoms of illness.16 Dance halls, movie theaters, playhouses, and other gathering places were ordered to fumigate their premises and to maintain proper ventilation; those that could not would be forced to make the necessary renovations to allow adequate fresh air flow. To help avoid a recurrence of the epidemic, the health department decided to initiate a public education campaign. The Department printed circulars and posters warning about influenza and the practices that recently had helped spread it.17

Syracuse’s theaters reopened to capacity crowds as residents rushed to see plays and movies after several weeks of entertainment-less evenings. Similarly, church pews were filled on Sunday. Residents seemed eager to return to their normal routines of urban life. As the local newspaper put it, “The red-lettered placards of the Bureau of Health were the only reminders of the period through which the city has passed.”18

Overall, Syracuse’s excess death rate for the second wave of the epidemic (September 1918 through March 1919) was 541 deaths per 100,000 people, a rate comparable to most other Upstate New York communities as well as cities across the greater Northeastern region. But, unlike most other area cities (and indeed communities across the United States)–which continued to experience cases and deaths through early-spring 1919–Syracuse’s bout with influenza essentially ended by the last days of November. In January and February 1919, the city did have a slight increase in influenza cases and deaths, but the numbers were hardly above the baseline for seasonal outbreaks of the disease. By far, the worst of Syracuse’s influenza epidemic had passed by the last days of October.

Notes

1 “Need Not Fear Epidemic Here of Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 21 Sept. 1918, 6.

2 “Doctors Work Night and Day Caring for Influenza Cases,” Syracuse Post Standard, 26 Sept. 1918, 6; “12 More Soldiers Dead in epidemic of Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 27 Sept. 1918, 6.

3 “Percentage of Deaths under Other Camps,” Syracuse Post Standard, 28 Sept. 1918, 6.

4 “Camp Officers Gratified by Day’s Report,” Syracuse Post Standard, 1 Oct. 1918, 6.

5 “Physicians to Report Influenza Cases; 7 Deaths Occur Among Camp Soldiers,” Syracuse Post Standard, 4 Oct. 1918, 7.

6 “City Takes Steps to Combat Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 5 Oct. 1918, 6.

7 “Schools, Theaters, Churches and Public Meeting Places Closed,” Syracuse Post Standard, 7 Oct. 1918, 6; “Public Library and Branches Ordered Closed by Trustees,”; “Public Library and Branches Ordered Closed by Trustees,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6.

8 “City Continues Vigorous Efforts to Stamp out Epidemic Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6.

9 “Large Classes Suspended at University by Dr. Day,” Syracuse Post Standard, 8 Oct. 1918, 6; “SATC Men Put Under Quarantine,” Syracuse Post Standard, 9 Oct. 1918, 6.

10 “Activities of Boy Scouts Curtailed by the Epidemic,” Syracuse Post Standard, 9 Oct. 1918, 6.

11 “City Continues Vigorous Efforts to Stamp out Epidemic Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6; “Appeals for Aid,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6.

12 “Drop in New Cases of Influenza Indicated in Physicians’ Cards,” Syracuse Post Standard, 15 Oct. 1918, 6.

13 State of New York, Thirty-ninth Annual Report of the Department of Health, for the Year Ending December 31, 1918, Vol. 1 (Albany: J. R. Lyon Company, 1920), 86.

14 “Health Officer Orders Doctors to Report Cases of Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 17 Oct. 1918, 7.

15 “New Cases of Influenza Slowly Decreasing Here,” Syracuse Post Standard, 19 Oct. 1918, 7.

16 “Ban on Public Meetings Will End on Friday,” Syracuse Post Standard, 23 Oct. 1918, 7; “Schools Again Take up Work Following Ban,” Syracuse Post Standard, 28 Oct. 1918, 6.

17 “Teach Public How to Avert Second Plague,” Syracuse Post Standard, 24 Oct. 1918, 7.

18 “Theaters and Churches Filled to Capacity Show Fear of Epidemic is Over,” “Theaters and Churches Filled to Capacity Show Fear of Epidemic is Over,” Syracuse Post Standard, 28 Oct. 1918, 6.