Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Worcester, Massachusetts

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

On September 19, Worcester experienced its first influenza-related death. Young James W. Roche, only 25 years old, had come from the Newport Naval Training School on furlough to visit his parents at 142 West Street. Shortly after his arrival, he fell so ill with influenza that he was taken to City Hospital, where he subsequently died. Two days later, his mother died of influenza as well. Then, as if the family had not suffered enough, the father, a Worcester patrolman, died of influenza. The Roche family’s tragedy was also the start of Worcester’s epidemic.1,2

Aware of the epidemics unfolding in communities across Massachusetts and the threat now posed to his city, Worcester Mayor Pehr Gustaf Holmes immediately contacted the Board of Health and school officials to set a meeting for Monday, September 23 to discuss the situation.3 By the time they met, there were already scores of influenza cases in Worcester. City Hospital had so many cases that Superintendent Charles Drew feared that, unless the patients recovered quickly, the hospital would be forced to turn away new cases. Several nurses and doctors were sick with influenza, compounding the hospital’s troubles. St. Vincent’s Hospital had already barred visitors from entering in an effort to keep influenza away from patients. Drew suggested that the city begin meeting the crisis head-on by proactively erecting temporary emergency hospitals. Together with Mayor Holmes, the two issued an urgent appeal for volunteer graduate nurses 4 Although the epidemic was starting to grow worse, the Worcester Board of Health believed that if the public was careful about covering sneezes and coughs and if the ill remained in their homes and out of crowds, the disease could be combated.5

Several school principals, however, were not content with the Board’s wait-and-see approach. Cool, damp weather had left many classrooms unbearably cold, and five principals had taken advantage of a school board rule that allowed teachers to dismiss classrooms if the room temperature dipped below 60 degrees by closing their entire building. Their argument was that the damp and chilly conditions in the classrooms would help spread influenza. Two days later, on September 25, fifteen more schools closed either in part or in whole due to cold conditions and numerous complaints from concerned parents. The day after that, school officials ordered all Worcester public schools except North High School closed due to the cold, rainy weather. Mayor Holmes, previously determined not to use fuel until December 1, relaxed his position and released cords of wood for use in the city’s schools, tasking janitors with driving the dampness from the buildings but warning them to use only as much coal and wood as absolutely necessary.6

A Rudderless Ship

Worcester’s epidemic was undoubtedly growing worse, although, with influenza not listed as a reportable disease, no one could say for sure just how bad the situation really was. Board of Health Executive Officer James C. Coffey believed that it would be difficult if not impossible to get physicians to report cases of influenza unless Massachusetts authorities mandated them to do so. Thus far, the only sources of information on new cases were either hospital reports or newspaper accounts, neither of which accurately reflected the state of the epidemic. Neither Coffey nor Board of Health Chairman Dr. Edward Trowbridge seem inclined to issue a local decree making influenza reportable in Worcester, as countless other health officials across the United States had or would do in their own communities.

Indeed, no Worcester official seemed willing to take charge of the situation, instead opting to wait for state authorities to lead. When Acting Governor Calvin Coolidge issued a proclamation on September 24 recommending that all communities across the state immediately close their schools, theaters, and other public places and to cancel public gatherings, the Board of Health responded that it would only do so when directly compelled by the state.7 On September 26, the Massachusetts Emergency Public Health Committee requested that local authorities issue closure orders and public gathering bans. That evening, the Worcester Board of Health finally took action. Meeting well into the night with Mayor Holmes, who gave his full approval, the three-man committee unanimously voted to close immediately all schools (including private and parochial schools), theaters, movie houses, dance halls, public halls, and other places of amusement until the morning of Monday, October 7. The Board also ordered the water department to shut-off the flow to all public drinking fountains. The upcoming Fourth Liberty Loan parade was postponed, and the Liberty election cancelled. Churches and lodges were permitted to remain, although Holmes did ask the public to do their part by avoiding crowds.8 The action came none too soon. People were beginning to wonder if anyone was in charge. As one newspaper reported opined, “If there ever was a time in which the man of the hour was needed in Worcester it is today. And from the talk on the streets and all around the city no one appears on the scene large enough to grapple with it.”9 Now, at least, residents need only worry about the epidemic, and not whether their officials were up to the task of combating it.

Emergency Preparations

The situation was rapidly deteriorating. The local chapter of the Red Cross was receiving over a dozen calls for help each day, but there were too few nurses to answer them all. The police were ready and able to transport sick residents to City Hospital, but it was already full. It was also sorely lacking in nurses; nearly fifty nurses and attendants at City Hospital were sick with influenza. The Board of Health made tentative plans to establish an emergency facility at the Board of Health’s Belmont Hospital to handle more cases, but was reluctant to do so unless the situation grew more severe.10

United States Congressman Samuel E. Winslow believed the situation was severe enough already. To help ameliorate the overcrowding at City Hospital, Winslow–also head of the hospital’s board of trustees–coordinated with representatives of Worcester’s hospitals to establish and supervise an emergency hospital at the Worcester Agricultural Society buildings on the Greendale Fairgrounds. With the help of the E. J. Cross construction and the Norton manufacturing companies, volunteers began renovating and outfitting several buildings at the fairgrounds, including an old dance hall, with a goal of opening the facility on October 2.11 In addition to manpower, the Norton Company provided medical, lighting, and sanitary equipment for the emergency hospital, as well as three physicians.12 At Belmont, director Dr. May S. Holmes busied herself preparing an emergency ward.13

Despite the heroic efforts of the construction volunteers, work on preparing the Greendale hospital took a few days longer than initially anticipated and it did not open until Friday, October 4.14 The short delay mattered little anyway, as securing staff for the new hospital proved difficult; an estimated one-third of Worcester’s nurses were themselves ill with influenza. The city’s four hundred graduate nurses and thirty volunteers were already busy tending to home cases. The Board of Health and Worcester’s various nursing organizations made an urgent appeal for nurses and orderlies to staff the new facility. In an effort to make the work of the city’s 400 healthy graduate nurses and its 30 volunteers more efficient, the Board met with representatives of the Central Registry of Nurses, the District Nursing Association, and the Red Cross to develop a plan. The group decided that no more than one nurse should be stationed on any one given street in order to avoid duplication of effort. The Board also requested that undertakers hold only private funerals.15

The two emergency hospitals opened just in the nick of time. By October 7, all the regular city hospitals were completed filled, and the emergency hospitals were expected to reach capacity within a day. Dr. Charles Drew, Superintendent of City Hospital, decried the city’s lack of leadership and the inefficiency in the handling of Worcester’s epidemic. Early in the epidemic he had called for emergency measures to be taken so that the city would not be caught in this desperate situation. Now, Drew believed that decisions regarding the control of the epidemic should be placed in the hands of a single governing body with a strong executive to oversee all the nurses, volunteers, and physicians and to handle the issues of housing, caseloads, food and material aid, and the like. Although he never directly blamed Coffey, Trowbridge, or the Board of Health in general, it was clear that Drew placed little faith in their abilities or their management of the crisis.16

Meanwhile, both state and local officials tightened their epidemic control measures. On October 2, the state Board of Health made influenza a reportable disease.17 Finally, Worcester officials would have a better indicator of the progress of the epidemic. From what they knew already from the death certificates issued, it had become worse: over 140 residents had died from influenza or pneumonia in the nine days since the “official” start of the epidemic, although, due to the shortage of physicians available to sign death certificates, this number was assumed to be on the low side. Mayor Holmes himself was now sick with influenza. Initially reluctant to implement a closure order, on October 4 the Board voted to extend it for an additional week, through October 12. It also added churches to the list of closed places.18

The extension of the closure order meant that the popular Worcester Music Festival, scheduled to take place on October 7, would have to be postponed, and that the city’s Columbus Day Parade, scheduled for October 12, would be cancelled. Many residents were upset with the decision, most of all theater interests. The Worcester Theater Managers’ Association immediately protested the Board’s action, declaring it unfair that their businesses should be shuttered while the city’s saloons, bowling alleys, and pool halls be allowed to continue to earn money. The Association called for all non-essential businesses to be closed immediately so that the epidemic could be brought to a swift end. Joining them was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), particularly strong amongst Worcester’s large population of Swedish Protestants. The president of the local chapter of the WCTU, Amanda Peterson, wrote a scathing attack on city authorities for closing churches but not saloons. “Is it any healthier to pass your night in a saloon drinking some poisonous concoction mixed by some bartender who might find some more essential and manly trade than mixing drinks for these poor creatures,” she asked rhetorically, “say going to church and listening to the word of God?”19

By October 7, with the first several batches of daily case reports tabulated, the Board of Health could see that the influenza epidemic was still serious. Just over 100 cases had been reported two days earlier; now, that number had jumped to 357. Whether out of concern for the epidemic’s trend, pressure from constituents (angry theater managers and employees especially), or both, the Board voted to expand the list of public places affected by the order. In a sweeping addendum effective at midnight the next day, it now added all saloons, soda fountains, bowling alleys, pool halls, slot machine parlors, and public auctions to the list of closed businesses. The Board also banned bargain sales, limited the number of vehicles at funerals to four, and prohibited chairs at wakes and funerals to encourage shorter services.20

A Return to Normal?

Fortunately, Worcester had already weathered the worst of the epidemic. Unused to reporting cases of influenza and overtaxed in their other duties, initially many physicians were delayed in reporting influenza cases. This made it difficult for officials to discern with any degree of certainty the state of the city’s epidemic. Now, however, the figures appeared to be trending downward, despite some occasional hiccups in the reporting system. By October 12, the Board of Health was guardedly optimistic that the closure order could be removed shortly.21 Six days later, the Board met and decided that the epidemic situation had improved enough to allow Worcester to reopen. Starting at midnight on Tuesday, October 22, Worcester could return to business as usual and, on Wednesday morning, children could return to their classrooms.22

The news was met with mixed reception. Theater, saloon, pool hall, ice cream parlor, and other affected business owners were undoubtedly thrilled, and went straightaway to preparing for the reopening.23 Church leaders were divided. Catholic clergy claimed that conditions were normal in their parishes. A group of five priests had met with the Board during its deliberations on reopening the city and asked that they be allowed to hold services on that Sunday. Protestant ministers, on the other hand, thought that caution was the better part of valor. The Interdenominational Ministers’ Association presented the Board with a petition asking it to keep the closure order in place until the epidemic was over completely.24 Charles Drew, Superintendent at City Hospital was of a similar mind, and recommended that the Board move cautiously. The number of new cases was declining, he admitted, but the overall number was still quite high. The head of the District Nurses Association, Rosabelle Jacobus, agreed but used even stronger words. “It is absolutely ridiculous to think of yet lifting the ban on the closing of public places,” she told reporters. “Things are clearing up, but it has not yet cleared off; things are better, but it is not over.” Scores of parents spoke out against the Board’s action as well, stating that they would not send their children to school on Wednesday out of fear that they would get sick. Dr. Francis Underwood, a member of the school committee, agreed with these concerned parents. He blasted the Board of Health for not consulting with the school board–of which three of its members were physicians–before voting to rescind the closure order. He even went so far as to advise the parents of all of his patients as well as all parents with whom he had spoken to keep their children out of school for at least the remainder of the week.25

Despite the reaction from some groups, the reopening went ahead as scheduled. The number of new cases continued to drop, and the number of influenza patients in Worcester’s hospitals–including the emergency ward at Belmont and the Greendale facility–continued to decline.26 The Interdenominational Ministers’ Association quickly changed its stance, and voted to make the first Sunday after reopening a “Go-to-Church” day, urging all parishioners to attend services.27 Schools, of course, reopened, although some parents did indeed keep their children at home.28 By the end of October, Worcester’s various relief agencies concluded their influenza work. The epidemic was essentially over.

By mid-December, Worcester physicians were reporting an average of forty or so influenza cases per day to the Board of Health. City Hospital was caring for 25 influenza patients, and there were an additional 28 cases at the influenza ward at Belmont Hospital. Board of Health Executive Officer James Coffey announced that the Greendale emergency facility would reopen if necessary, but for now the situation did not warrant any further action. It is likely the Board would have had difficulty staffing Greendale if it did reopen, given that the city’s nursing organizations reported that their nurses were once again overworked by the recent spate of cases. The city’s affluent West Side was particularly hard hit, and Red Cross nurses were busy caring for the hundred or so patients there, leaving precious few nurses to tend to Worcester’s other cases.29

Conclusion

As December rolled into January, the epidemic finally came to a close. Doctor’s reported occasional cases throughout the winter, but they were far fewer in number and generally milder in nature than during the fateful days of October. Overall, Worcester physicians reported 6,884 cases of influenza and pneumonia and 1,294 resultant deaths to the Board of Health during the epidemic.30 That number is undoubtedly low, as influenza was not made a reportable disease until early-October and the reported case-fatality rate (CFR) was entirely too high. Typically, American cities experienced an influenza CFR (the number of people who died divided by the number of cases of influenza) of approximately 2.5%. For Worcester, that would place the number of influenza cases at an estimated 52,000, or nearly a third of its overall population. The city’s excess death rate (EDR) for the entire epidemic period (September 1918 through February 1919) was rather high: 655 per 100,000 people. By comparison, Lowell’s was 523, and Cambridge’s was 541, and Fall River’s was 621. Of Massachusetts’ cities, only Boston’s EDR (710) was higher.

Perhaps more important than these figures, however, is the way in which Worcester handled its epidemic. Saddled by an indecisive Board of Health with no clear leader and with a mayor who seemed equally unwilling to take charge, the city opted to take its cues from Massachusetts officials rather than plot its own course. It waited for state health officials to make influenza a reportable disease, leaving it with no good source of information on the severity of the epidemic during those critical early days. Likewise, the Board only moved to close public places after the state board of health strongly urged local communities to do so. As a result, Worcester’s public health response time (the period between the time when the city’s epidemic became severe enough for health officials to take notice and the time when the first control measures were adopted) was 15 days, the longest of Massachusetts’ major cities.

Notes

1 “First Influenza Death in City,” Worcester Evening Post, 19 Sept. 1918, 1; “Two in family die from grip,” Worcester Evening Post, 21 Sept. 1918, 1; “Follows Son and Wife in Death,” Worcester Evening Post, 24 Sept. 1918, 1.

2 “Five Schools Closed Because of Sickness,” Worcester Evening Post, 23 Sept. 1918, 1.

3 “City plans to fight influenza,” Worcester Evening Post, 21 Sept. 1918, 3.

4 With City Hospital Unable to Care for More Influenza, Situation is Alarming,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 24 Sept. 1918, 2; “City Hospital Staff Nurse Grip Victim,” Worcester Evening Post, 24 Sept. 1918, 1.

5 “Five Schools Closed Because of Sickness,” Worcester Evening Post, 23 Sept. 1918, 1.

6 “Five schools closed because of sickness,” Worcester Evening Post, 23 Sept. 1918, 1; “Dismiss 15 schools to prevent grip,” Worcester Evening Post, 25 Sept. 1918, 1; “City Will Not Close Schools or Theaters,” 26 Sept. 1918, 1; “Mayor Takes Action to Battle Grip in Schools,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 24 Sept. 1918, 18.

7 “City Will Not Close Schools or Theaters,” Worcester Evening Post, 26 Sept. 1918, 1.

8 “Health Board Orders Public Places Closed,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 27 Sept. 1918, 1; “Health Board Rulings for Fighting Influenza,” Worcester Evening Post, 27 Sept. 1918, 1.

9 “Hospital full, police worried,” Worcester Evening Post, 27 Sept.1918, 15.

10 “Nurses! Nurses! Heed this Call,” Worcester Evening Post, 27 Sept. 1918, 2; “Hospital Full, Police Worried,” Worcester Evening Post, 27 Sept. 1918, 15.

11 “To Open Hospital in Greendale Park,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 30 Sept. 1918, 1; “Big Funerals and Wakes Prohibited,” Worcester Evening Post, 30 Sept. 1918, 1; Annual Report of the Board of Health of the city of Worcester Massachusetts for the Year ending December 30, 1918 (Worcester, MA: Commonwealth Press, 1919), 299.

12 Forty-eighth Annual Report of the Trustees of the City Hospital Worcester, Massachusetts for the Year ending November 30, 1918 (Worcester, MA: Commonwealth Press, 1919), 481; “Emergency Hospital for Influenza Epidemic,” Norton Spirit, vol. 5, no. 3 (October 1918), 1, 6; “Patriotic service,” Norton Spirit, vol. 5, no. 3 (October 1918), 2.

13 “Washington Closes Theaters,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 4 Oct. 1918, 20.

14 “Washington Closes Theaters,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 4 Oct. 1918, 20.

15 “Big Funerals and Wakes Prohibited,” Worcester Evening Post, 30 Sept. 1918, 1.

16 “No Abatement Anywhere in Spread of Influenza,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 7 Oct. 1918, 12.

17 “Must Report Cases of Grip in This City,” Worcester Evening Post, 2 Oct. 1918, 1.

18 “Public Places of City Closed Another Week,” Worcester Evening Post, 4 Oct. 1918, 1.

19 “Theater Men Protest on New Order,” Worcester Evening Post, 4 Oct. 1918, 1; “Theatrical Men Act on Situation,” Worcester Evening Post, 5 Oct. 1918, 2; “’Close the Drinking Dens but Leave the Churches Open,’ says Mrs. Peterson,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 5 Oct. 1918, 2.

20 “Saloons Will Be Closed Tomorrow,” Worcester Evening Post, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

21 “May Lift the Closing Ban Next Saturday,” Worcester Evening Post, 12 Oct. 1918, 2.

22 “Closing Ban off Tuesday at Midnight,” Worcester Evening Post, 18 Oct. 1918, 1.

23 “Health Board Lifts Ban and Worcester is Itself Again,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 23 Oct. 1918, 16.

24 “Worcester Health Board May Not Remove Grip Ban,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 18 Oct. 1918, 18; “Closing Ban off Tuesday at Midnight,” Worcester Evening Post, 18 Oct. 1918, 1.

25 “Ridiculous to Reopen Public Places, Says Nurse Jacobus,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 18 Oct. 1918, 18; “Health Board Lifts Ban and Worcester is Itself Again,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 23 Oct. 1918, 16.

26 “Health Board Lifts Ban and Worcester is Itself Again,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 22 Oct. 1918, 16.

27 “Go-to-Church Sunday Urged,” Worcester Evening Post, 25 Oct. 1918, 9.

28 “Catholic Emergency for Grip Sufferers Closes Tonight at 6 o’clock,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 24 Oct. 1918, 8.

29 “Plan No Drastic Anti-Grip Move,” Worcester Evening Post, 13 Dec. 1918, 2; “Fear Influenza is Paying City a Second Visit,” Worcester Evening Post, 18 Dec. 1918, 2; “Physicians Report 54 New Cases,” Worcester Daily Telegram, 19 Dec. 1918, 24; “West Side of the City Full of Influenza,” Worcester Evening Post, 31 Dec. 1918, 1.

30 “Annual Report of the Board of Health of the City of Worcester, Massachusetts for the Year ending December 30, 1918 (Worcester: Commonwealth Press, 1919), 883.

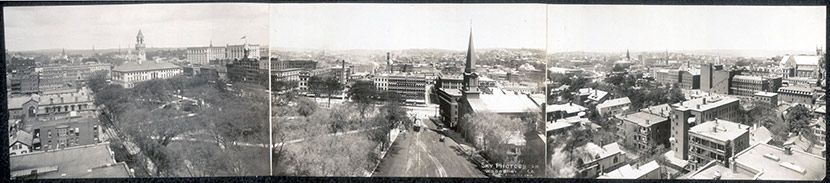

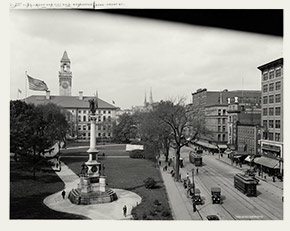

Click on image for gallery.

View of Worcester Common and City Hall, from Front Street, ca. 1910-1920.

Click on image for gallery.

View of Worcester Common and City Hall, from Front Street, ca. 1910-1920.

Click on image for gallery.

Worcester Memorial Hospital, ca. 1910. Built in 1888, the facility was endowed by wealthy local businessman Ichabod Washburn. The hospital was located on Belmont Street near Oak Avenue. Memorial Hospital had a normal capacity of 130 beds, with room for many more cases in times of emergency. From: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Click on image for gallery.

Worcester Memorial Hospital, ca. 1910. Built in 1888, the facility was endowed by wealthy local businessman Ichabod Washburn. The hospital was located on Belmont Street near Oak Avenue. Memorial Hospital had a normal capacity of 130 beds, with room for many more cases in times of emergency. From: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.