Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Richmond, Virginia

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

August 1918 was a scorcher in tidewater Virginia. Drilling in uniform in the heat and humidity of Petersburg, 25 miles south of Richmond, must have been grueling for the nearly 48,000 soldiers of Camp Lee.1 Little did they know that, as bad as the conditions were, they were about to get a whole lot worse. For only a few weeks later, influenza arrived in camp.

The first case of influenza appeared in a new inductee, who was admitted to the camp infirmary on the evening of Friday, September 13 with symptoms of severe respiratory disease. Camp doctors were not sure of the illness, but they suspected influenza. Within a few hours, ten more cases of the new malady were reported in different parts of the camp. By the morning of September 17, that number had grown by 500. Two days later, there were over 1,000 cases in Camp Lee, more than could be tended to in the camp hospital. Medical personnel now knew they were dealing with a quickly growing influenza epidemic.2 In an attempt the keep the disease contained to the camp, the commanding general, Brigadier General Charles A. Hedskin, forbid all public gatherings within the camp, and closed the YMCA building, the Knights of Columbus hall, and the movie houses. Visitors were also prohibited. The camp designated a squad room in each barracks as an infirmary; a curtain made from a halved sheet was hung around the head of each cot in an effort to contain germs, and each sick man carried through the camp had to don a gauze mask. Hedskin, did not think a general quarantine of the camp would prove effective given that the disease was already so rampant all along the East Coast. More important, the general believed, a quarantine would delay troop training sessions.3 Eager to prepare his troops for battle, Hedskin pushed the soldiers to train hard, and many returned to their duties before fully recovering from influenza. The crowded camp conditions, combined with over-exerted soldiers, were a recipe for disaster. The only safe place in the camp seemed to be the officers’ training school, which had been strictly quarantined.4

Meanwhile, knowing that soldiers from Camp Lee regularly came to Richmond for entertainment and fearing that they would bring the disease with them, city health officer Dr. Roy K. Flannagan and Virginia Health Commissioner Ennion G. Williams met to discuss methods on preventing a potential epidemic among civilians. The two men decided that, for the time being, a public education campaign was the best way to deal with the threat. Posters and pamphlets were printed for distribution in the schools, urging the public to refrain from putting their fingers, foreign objects, or common drinking cups in their mouths, and to cover their coughs and sneezes. As of yet there were no reported cases of influenza in Richmond, although Flannagan and Williams fully realized that, since influenza had only become a reportable disease in Virginia earlier that year, it was possible that physicians had neglected reported cases.5

On September 28, as the epidemic at Camp Lee increasingly grew worse and as several hundred cases appeared in Richmond, Flannagan requested that the War Camp Community Service’s dances and entertainments for the soldiers from Camp Lee be cancelled. The Department of Health also advised Richomonders to refrain from inviting soldiers into their homes for Sunday dinner, as had become the custom. “So far as I can understand,” Flannagan complained, “there is no quarantine at Camp Lee. Hundreds of soldiers from that camp daily visit Richmond and these must, to a greater or lesser extent, spread the disease.” For now the measures were only recommendations, although Flannagan noted that if not followed he indeed would issue a public health edict outright banning the dances as well as closing movie houses. For the time being, in addition to these recommendations, Flannagan settled on a simple policy of forbidding sick children from attending school.6

As in Camp Lee, Richmond’s epidemic took off like gangbusters. Within a few days the city had over 600 cases. Already Richmond’s nurses were being overrun. A roster of 75 nurses had been mustered, but still dozens of calls for help had gone unanswered. Flannagan plead for every man or woman, white or African American, with any nursing experience to lend assistance, and enlisted the help of the Red Cross to gather as many graduate and practical nurses as possible. Believing that the key to controlling the outbreak lay not necessarily in social distancing but in proper ventilation, he ordered that all churches and theaters ensure a steady supply of fresh air to their congregants and patrons. Those that did not do so were threatened with closure.7 Some called for the barring of Camp Lee soldiers from entering Richmond, but military officials there stated that such a move would have little effect on the city, given that the civilian population was already well seeded with cases.8 Meanwhile, Flannagan and Williams traveled to Richmond schools to give lectures on influenza prevention and treatment to schoolchildren.9

It did not take long for Flannagan and Williams to change their minds. On October 5, with outbreaks in nearly every community across Virginia and over 2,000 cases in Richmond, the State Department of Health issued a recommendation advising local health departments to ban all public gatherings and close churches, theaters, movie houses, and other such places. Schools closures were not recommended; instead, teachers were asked to monitor students and to send home sick children.1 That same day, upon Flannagan’s request, the city’s board of directors issued a closure order, adding public and private schools to the state’s list. The order went into effect on October 6. Richmond’s soft drink parlors and drugstore soda fountains, having enjoyed a one-day reprieve, were added to the list the next day. The Virginia State Fair, scheduled to open on October 7, was initially exempted from the order because Flannagan believed that visitors would not be subjected to any more risk there than if they were walking around the streets of downtown Richmond.11 State health officials disagreed, and ordered the fair closed as well.12 Richmond was shut tight.

With social distancing measures in place, officials turned their attention to the city’s healthcare system and its overworked nurses and physicians. Flannagan divided Richmond into four sectors and assigned a doctor and nurses and volunteers to each to eliminate duplicate efforts. The Richmond Academy of Medicine and Surgery issued an appeal for all specialists to lend their aid, as did the Red Cross and the Visiting Nurses’ Association. The latter worked with Richmond’s churches to establish soup kitchens to feed families too sick to feed themselves or where the primary breadwinner had fallen ill and the family had lost those wages. At the request of the United States Public Health service, the Red Cross had 15,000 pamphlets printed with recommendations on how to keep healthy. The city council appropriated $15,000 so that John Marshall High School, now unused, could be converted to a 500-bed emergency hospital.13 The hospital was up and running the next day, with ten nurses on duty. By 10:00 am there were already 55 patients in beds and 30 more on their way.14

It was scarcely the end of the first week in October, and already health officials estimated there were 10,000 cases within city limits, and predicted as many as 1,500 deaths in the next six weeks.15 Among the cases was Dr. Lawrence T. Price, director of the emergency hospital, now at home resting. In his place temporarily served Dr. E. C. L. Miller of the Medical College of Virginia (now part of Virginia Commonwealth University).16 State Health Commissioner Williams fell ill a few days later, and was confined to his home as well.17 Several other city officials were also down with influenza.18 One city commissioner exclaimed that he was “fearful of the greatest calamity that has befallen the city since the war.”19 Richmond would be lucky, some experts estimated, if it experienced 30,000 cases total and a six percent death rate.20

Richmond’s resources were being taxed to the limit. Milk was in short supply, partly owing to the number of sick dairy and distribution employees and partly due to physicians recommending it as nourishment for the ill. The shortage had grown so severe that city inspectors visited the Richmond jail to select inmates for work in the dairies. Some even expected the city the take over the dairies.21 More than milk, nurses were desperately needed. Doctors at the John Marshall emergency hospital were so frantic that they temporarily put aside their prejudice and issued an open letter to all residents asking for nurses of any race or gender.22 Some called for mandatory service, but state Attorney-General John R. Saunders stated that there was no official authority by which nurses could be commandeered for epidemic work.23 With the emergency hospital at capacity, the city opened Bellevue Junior High School for overflow white patients and the Baker School for African American patients. A group of 22 black physicians met to organize the staff for Baker, and elected Dr. William H. Hughes as their chief, with the others volunteering their services.24

Fortunately, the crest of the epidemic had been reached. As the second half of October rolled by, conditions continued to improve. On October 16, the John Marshall hospital was still full of recovering patients, although doctors there expected to release an increasing number of them to complete their convalescence at home. By October 28, the hospital had just 180 patients – about a third the number of the previous week – and announced it was no longer accepting new patients except in extreme circumstances. The remaining patients were relocated to a central area in the building so that the rest of the facility could be cleaned in preparation for the imminent reopening of Richmond’s schools.25

Both Flannagan and Acting State Health Commissioner Dr. Garnett, in charge of the state’s epidemic control measures while Ennion Williams recovered from his bout with influenza, were optimistic that the epidemic was truly over and that the closure order and gathering ban soon could be removed. On October 29, Garnett announced that conditions across Virginia had improved enough to allow local communities to decide when to remove their restrictions.26 The next day, Flannagan notified the city administrative board that churches would be allowed to hold Sunday services on November 3, and that the other restrictions would be removed Monday, November 4. Flannagan admitted that he expected the number of new daily cases to rise slightly as a result, but believed that proper ventilation in public places and care on the part of residents would keep the situation in hand.27 Richmonders – and especially business owners – eagerly awaited what they assumed would be the board’s rubber stamp endorsement.

The situation immediately grew more complex than that, however. A group of physicians from the Richmond Academy of Medicine and Surgery sent the administrative board a letter asking that discussion of removing the restrictions be tabled until the Academy could first discuss the epidemic at its upcoming meeting, scheduled to take place the evening of October 31. Dr. Thomas Murrell, head of the Academy, added that he believed lifting the bans at present would be a mistake. The administrative board, concerned with Murrell’s misgivings and Flannagan’s statement that there would be a slight rise in new cases, temporarily tabled the discussion. Ennion Williams, now fully recovered from influenza and back at his post, expressed his dismay at the situation. He believed that the state board of health clearly had placed authority to remove the closure order in the hands of local health departments, not in city councils and especially not in the Richmond Academy of Medicine and Surgery.28

The next day the administrative board reconvened, with several ministers and theater owners and managers present. Almost immediately Flannagan – in Charlottesville tending to his sick brother – telephoned the board to reverse his previous recommendation to rescind the closure order, citing the opinions of several Academy of Medicine and Surgery physicians as the reason for changing his mind. With leading physicians and now the health officer against reopening, the administrative board once again tabled the matter, leaving Richmond’s public gathering spots closed and many of its clergy, theater owners, and even school officials upset. At least one theater owner, on Flannagan’s previous word that theaters would be allowed to reopen on November 4, had arranged for a show. Now, he grumbled, he would lose $3,500. Ministers argued that holding Sunday services would not endanger the health of the community. The head of a private school complained that Flannagan had explicitly told him it would be safe to notify pupils and parents that their school would reopen on Monday, November 4. He had sent letters to parents and now had to scramble to notify them of the mistake.29

The administrative board debated the issue once again on November 2, this time behind closed doors. Members were split as to whether or not to lift the closure order, but in light of Flannagan’s withdrawal of his recommendation they let the matter rest. Meanwhile, Flannagan found himself beset by angry theater owners, two of which traveled to Charlottesville to complain to the health officer in person. Flannagan now waffled. In a letter to chief city commissioner Graham Hobson, he stated that he believed the closure order safely could be lifted, but that delaying action would improve public health. Flannaga told Hobson he was not “irrevocably committed” to lifting the closure order.30 No one, it seemed, wanted to take charge of the situation for fear that the epidemic would return in force.

Two days later, the administrative board voted to lift the closure order and gathering ban effective immediately. Flannagan had returned to Richmond, where he stated that conditions no longer warranted “any further penalizing of the public.” Influenza and pneumonia would continue to circulate throughout the winter, he added, but Richmond’s epidemic was over. If the city waited until the disease was completely gone to reopen its businesses, it would be waiting for a very long time. On the other side of the debate was the Academy of Medicine and Surgery and other like-minded physicians and nurses, who told Commissioner Hobson that lifting the order would be “nothing short of a public calamity” that would result in the deaths of hundreds. After a lengthy debate, the administrative board was still split. One commissioner requested that he be given more time to deliberate his vote. Hobson denied the request and his vote was counted as an abstention. The result was a break in the deadlock: the board voted two-to-one to lift the closure order effective immediately.31

Proprietors of affected establishments were elated, and went to work straightaway to prepare for business once again. The school board, initially prepared to admit pupils that day, scrambled to set a new date for schools to reopen – Wednesday, November 6. The John Marshall and Baker emergency hospitals were in various stages of being fumigated and cleaned and were almost ready for classes but would not reopen for several more days. Children with symptoms of influenza or coming from homes where there was an active case of influenza would not be allowed to return to their classrooms. To make up for the three weeks of lost instruction time, the school board voted to shorten vacations and to lengthen the school year.32 The unexpected vacation had come at a price.

As Flannagan predicted, influenza was not yet gone from Richmond. By early-December, the disease had reached near-epidemic levels once again. Hospitals, just recovering from the epidemic workload and now near capacity once again, announced that they would not accept any more influenza patients, leaving victims to be cared for at home or in a private facility. Commissioner Hobson refused to consider establishing another emergency hospital, calling it an unnecessary expense. When Price proposed opening the unused top floor of City Home Hospital to influenza patients, Hobson expressed forbade it. “I will not permit and you are directed not to receive any influenza patients at the city home,” he told Price. “These institutions have run $10,000 over their appropriations and must not take any more.” Hobson asserted that many of those treated previously at the John Marshall emergency hospital, despite being “amply able” to pay for their treatment, had instead left the city to foot the bill.33

Flannagan assured the public that, because far fewer were dying, no restrictions would be put in place. He warned residents to keep their bodies and their homes clean, and to avoid crowding on streetcars or in homes. Most affected were the poorer sections of Richmond, as well as the well-to-do West End neighborhoods only lightly touched by the epidemic in October.34 This latter fact was, as Flannagan realized, the key. As he wrote in his annual report to Mayor George Ainslie, influenza was now “playing return engagements everywhere, and nothing that is done by health departments, whether of Army, Navy, State or City, seems to do more than to temporarily check it. Renewed assaults by it apparently mean to take in the whole susceptible population.”35 The disease simply had to run its course.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Murrell and the Academy of Medicine and Surgery were unhappy with Flannagan’s position. He, along with many other physicians, wanted to see Richmond’s schools closed once again, claiming that many of the new cases were among children. Superintendent of Schools Albert Hudgins Hill disagreed, arguing that the situation did not warrant another closing. According to his attendance figures, the absentee rate had increased by only about five percent. Only a quarter of these, Hill surmised, were actually home with influenza, while the others were absent due to parents’ fears or teachers turning away students from infected homes. The schools already had to struggle to make up lost time; the Christmas break was now limited to only a week. A second closure would make it impossible for schools to properly educate students.36 On December 14, the Administrative Board tabled Murrell’s suggestion until it could consult with Flannagan, expected to return the next day from the American Public Health Association meeting in Chicago.37

The attendance rate in Richmond’s public schools continued to drop. Before the epidemic, the average daily attendance across the school district was approximately 24,000. By December 18, that number had declined to 15,705. Some 4,000 students were excluded from school because there was an active case of influenza in their home. That still left nearly 4,300 students absent either because of illness or because of overly concerned parents. Altogether, nearly a quarter of the city’s public school students were absent as the Christmas break approached; in some classrooms, fifty percent of the students were absent. With the Christmas holiday break just around the corner, Richmond officials decided not to issue a forced closure order.38 By the time the children returned from their holiday break, the influenza situation had improved greatly.

Between the start of the outbreak and the end of the year, a total of 20,841 cases of influenza were reported. Of these, 946 victims died as a result of influenza or pneumonia, nearly a quarter of all of Richmond’s deaths for the entire year.39 The disease rolled on into 1919, adding 132 deaths by early-February.40 Overall, Richmond’s death rate due to the epidemic was 508 per 100,000, higher than the average amongst Southern and Midwestern cities, but slightly lower than that of most other East Coast communities. As Flannagan wrote in his department’s annual report to the mayor, despite anticipating influenza’s arrival in Richmond, “no amount of forethought, in the absence of a sufficient number of doctors and nurses, could have prepared us for the tidal wave of disease and death that all but overwhelmed the city.” Such was the assessment of Richmond’s epidemic by Dr. Roy Flannagan.41

Notes

1 The average strength of Camp Lee in August 1918 was 47,695, and for September was 52,598. See “Table 8. Strength of specified camps, total enlisted men, by months, Sept. 1, 1917 to Dec. 31, 1919, inclusive,” in Maj. Gen. M. W. Ireland, ed. The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Vol. 15: Statistics, Part Two – Medical and Casualty Statistics (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1925), 32.

2 “Base Hospital Filled by Influenza Epidemic,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 17 Sept. 1918, 7; “One Thousand Soldiers Will Become Citizens,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 19 Sept. 1918, 2.

3 “Strange Malady Causes Camp Lee Quarantine,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 15 Sept. 1918, 8; “Base Hospital Filled by Influenza Epidemic,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 17 Sept. 1918, 7.

4 “Larger Base Hospital Planned for Camp Lee,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 29 Sept. 1918, 10. The veterinary staff had been quarantined as well, but unfortunately did not fare as well. See “Influenza Responsible for 167 Deaths at Camp,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 10 Oct. 1918, 3.

5 “Crusade against Spanish Influenza is Being Waged by State Health Officers,” Richmond News-Leader, 18 Sept. 1918, 1.

6 “Spanish Grip in Modified Quarantine,” Richmond News-Leader, 28 Sept. 1918, 1; “Spanish Influenza Makes Gains in Richmond; Cases Total 340, Doctors Busy,” Richmond News-Leader, 30 Sept. 1918, 2; “May Close Movie Houses to Protect Public Health,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 29 Sept. 1918, 10.

7 “Influenza Safeguards Taken by Dr. Flannagan,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 2 Oct. 1918, 14.

8 “Influenza Responsible for 167 Deaths at Camp,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 3 Oct. 1918, 3.

9 “With 466 Cases Reported, Authorities Are Closely Watching Fly Situation,” Richmond News-Leader, 1 Oct. 1918, 1.

10 “Influenza Situation Considered Grave,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 5 Oct. 1918, 10.

11 “Epidemic Forces Drastic Action,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

12 “Turns Schools into Grip Hospitals; Soda Founts Closed,” Richmond News-Leader, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

13 “Quickly Organize to Fight Plague of Spanish Grip,” Richmond News-Leader, 8 Oct. 1918, 1;

14 “Hospital Head is Stricken Down,” Richmond News-Leader, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

15 “Flu Besieges City; 10,000 Cases Here,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 8 Oct. 1918, 10.

16 “Hospital Head Is Stricken Down,” Richmond News-Leader, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

17 “More Doctors and Nurses Stricken Ill with Malady that Grips the Community,” Richmond News-Leader, 10 Oct. 1.

18 “Influenza Deaths to Date Total 112 out of 3,853 Cases Reported Officially,” Richmond News-Leader, 11 Oct. 1918, 1.

19 “Turn Schools Into Grip Hospitals; Soda Founts Closed,” Richmond News-Leader, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

20 “Flu Besieges City; 10,000 Cases Here,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 8 Oct. 1918, 10.

21 “City Probably Will Take Over Operation of Dairy Business, with Jail Help,” Richmond News-Leader, 12 Oct. 1918, 1.

22 “Doctors Beg for Nurses, Men and Women Alike,” Richmond News-Leader, 12 Oct. 1918, 1.

23 “Influenza Deaths to Date Total 112 out of 3,853 Cases Reported Officially,” Richmond News-Leader, 11 Oct. 1918, 1.

24 “Peak of Grip Epidemic is Reached Here,” Richmond News-Leader, 14 Oct. 1918, 4.

25 “Doctors Think Influenza Situation Here Continues to Improve,” Richmond News-Leader, 16 Oct. 1918, 1; “Grip Patients No Longer Admitted,” Richmond News-Leader, 26 Oct. 1918, 9; “Epidemic Tide Continues to Ebb,” Richmond News-Leader, 29 Oct. 1918, 15.

26 “Epidemic Tide Continues to Ebb,” Richmond News-Leader, 29 Oct. 1918, 15.

27 “Will Lift Ban at Midnight Saturday,” Richmond News-Leader, 30 Oct. 1918, 1.

28 “Defers Action on Lifting the Ban,” Richmond News-Leader, 31 Oct. 1918, 1.

29 “Board Tables Flannagan’s Original Letter,” Richmond News-Leader, 1 Nov. 1918, 1.

30 “Ban Will Not be Lifted Tomorrow,” Richmond News-Leader, 2 Nov. 1918, 1.

31 “Ban is Lifted, Board Voting Two to One in Favor,” Richmond News-Leader, 4 Nov. 1918, 1.

32 “Open Schools at Date to be Fixed,” Richmond News-Leader, 4 Nov. 1918, 1; “Pupils from Grip Homes Barred,” Richmond News-Leader, 5 Nov. 1918, 13. John Marshall High reopened on Thursday, November 7, and Baker School on Monday, November 11. See “High School’s Opening is Tomorrow, Richmond News-Leader, 6 Nov. 1918, 2.

33 “Influenza Patients Will Not Be Received In City Hospitals Until Notice,” Richmond News-Leader, 5 Dec. 1918, 16.

34 “Influenza Again Is Almost an Epidemic” Richmond News-Leader, 2 Dec. 1918, 1.

35 Roy K. Flannagan, “Report of the Chief Health Officers, in Annual Report of the Health Department of the City of Richmond, Va., for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Richmond: Clyde W. Saunders, 1919), 7.

36 “Sees No Reason for Closing Public Schools at This Time on Account of the Influenza,” Richmond News-Leader, 13 Dec. 1918, 1.

37 “Closing of Schools Is Deferred by the Administration Until Dr. Flannagan Returns,” Richmond News-Leader, 14 Dec. 1918, 1,13.

38 “Only 87 Cases Reported up to Noon,” Richmond News-Leader, 18 Dec. 1918, 1.

39 Roy K. Flannagan, Annual Report of the Health Department of the City of Richmond, Va., 1919, printed by Clyde W. Saunders, City Printer, 7.

40 “January Deaths Less than Half as Many as in October,” Richmond News-Leader, 7 Feb. 1919, 7.

41 Roy K. Flannagan, Chief Health Officer Richmond, in 1918 City Health Report

Click on image for gallery.

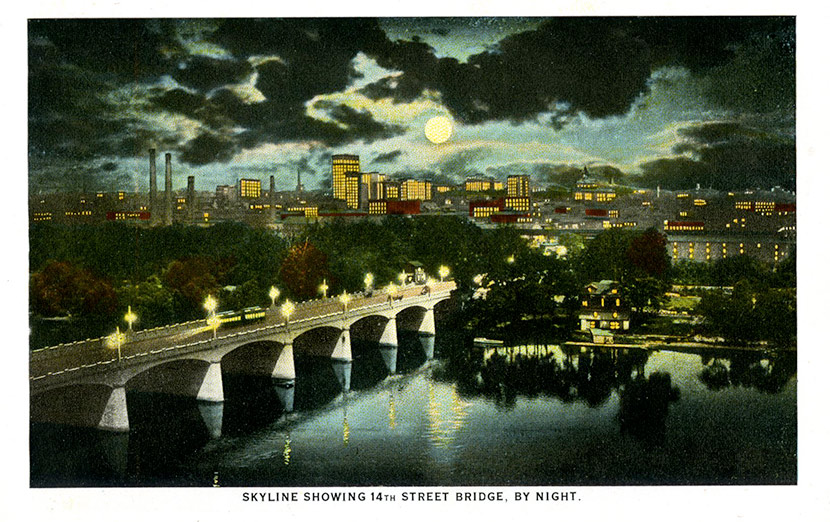

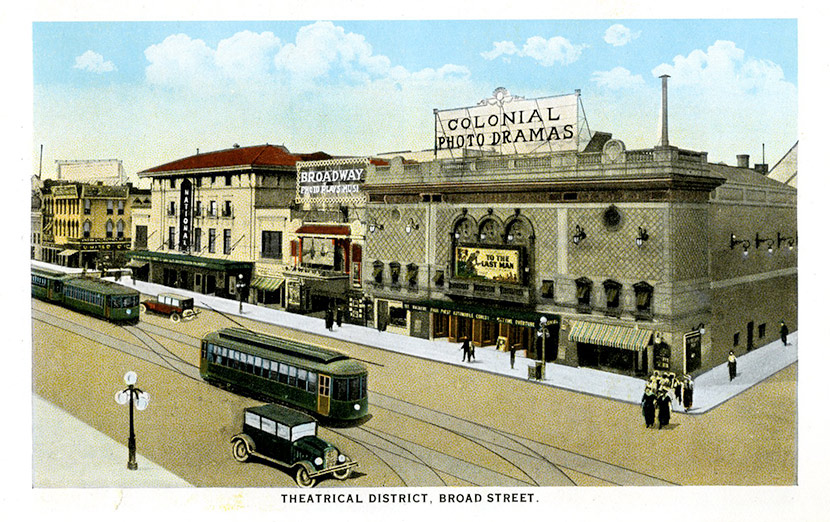

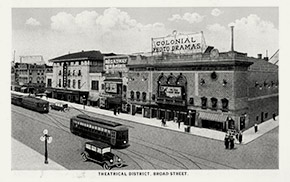

Richmond’s theater district along the 700 block of Broad Street, then known then as Theatre Row. This postcard is from the 1920s, but the area would have looked much the same during the 1918 epidemic, when all theaters were closed.

Click on image for gallery.

Richmond’s theater district along the 700 block of Broad Street, then known then as Theatre Row. This postcard is from the 1920s, but the area would have looked much the same during the 1918 epidemic, when all theaters were closed.

Click on image for gallery.

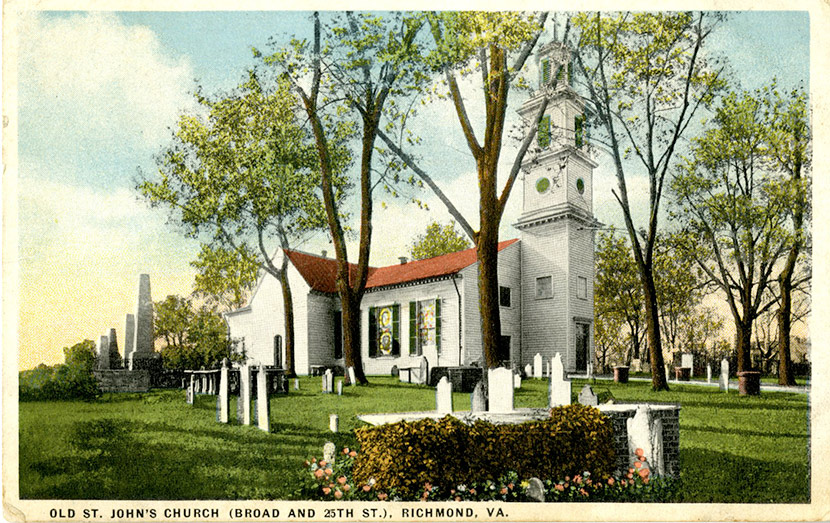

St. John’s Church at Broad and 25th Streets. The structure was built in 1741, and was the site where Patrick Henry delivered his famous “Give me liberty or give me death” speech on March 23, 1775. During Richmond’s influenza epidemic, St. John’s – along with the city’s other churches – was temporarily closed.

Click on image for gallery.

St. John’s Church at Broad and 25th Streets. The structure was built in 1741, and was the site where Patrick Henry delivered his famous “Give me liberty or give me death” speech on March 23, 1775. During Richmond’s influenza epidemic, St. John’s – along with the city’s other churches – was temporarily closed.