Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

New York, New York

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

When the Norwegian vessel Bergensfjord steamed into New York City’s harbor on August 11, 1918, an unusual welcoming committee awaited on shore. The ship held 11 crew and ten passengers infected with a new and particularly aggressive form of influenza. On the pier were ambulances and health officer for the Port of New York, who immediately whisked the ill sailors to a city hospital. Sailors who had become ill during the voyage but were now recovering as well as those in contact with the sick while on board where put under close surveillance by New York City Department of Health nurses.1 New York – no stranger to epidemics – had a long-standing tradition of disease surveillance, isolation, and quarantine, and it was this mechanism that went into immediate effect.

Over the course of the next several weeks, more ships bearing ill sailors arrived at New York harbor. On August 16, the Nieuw Amsterdam arrived in New York from Rotterdam, with 22 passengers aboard sick with influenza. On September 4, a French liner Rochambeau arrived with 22 new cases of influenza on board; two victims had already died at sea. The city’s health department placed all the ill men in isolation at the Willard Parker Hospital on East 16th Street and at the French Hospital on W. 34th Street.2 In an attempt to lessen the likelihood of influenza spreading to New York’s population, health commissioner Dr. Royal S. Copeland placed the entire Port of New York under quarantine on September 12. The difficulty, Copeland admitted, was that other East Coast ports may not be as rigid in their methods of disease control, therefore allowing influenza to enter New York from another city.3 A few days later, 23 new cases were discovered among sailors from the United States Navy.4 Then, on September 16, thirteen seamen were discovered ill with influenza and transferred from their naval training ship to the Kingston Avenue Hospital in Brooklyn. Copeland told the public that there was no need for alarm.5

Still, Copeland tightened the city’s disease control measures. On September 17, the city’s Board of Health added influenza to the list of reportable diseases, thus, according to the sanitary code, requiring all cases to be isolated.6 Copeland announced that homes with cases would be quarantined while the patient recovered, while cases in tenements would be isolated in a city hospital. The move came none too soon: three civilian and two military cases were discovered the next day and placed under isolation.7 Copeland worried that the disease would spread to New York’s schoolchildren, and he cautioned schools to send home children who were sneezing or coughing in class. To the general public, he had signs printed and distributed warning of the dangers of influenza, how to prevent it, and how to treat it.8 He also met with representatives from theaters, movie houses, and public transportation to enlist the aid of managers in preventing the spread of influenza.9 Meanwhile, Dr. William H. Park, head of the city’s Bureau of Laboratories, busied himself and his staff with trying to identify the causative microbe in the hopes of developing a vaccine.1

By September 24, New York had well over 100 new cases of influenza with which to deal. Copeland worried about the growing number of cases and his ability to isolate them all. Given that the case rate was likely to rise quickly, hospitals would soon no longer be able to place cases in isolation wards; general wards would have to be opened to influenza patients. He sent instructions to hospitals on how to handle epidemic caseloads.11 Four days later, city physicians reported an additional 324 cases, with Brooklyn being the worst hit borough. Copeland remained calm, telling reporters and residents that there was no cause for alarm. New York had experienced a total of approximately 1,000 influenza cases thus far, he said, only a tiny percentage of the city’s 5.6 million population. He did ask the city government for $5,000 with which to fight the growing epidemic, however. The Board of Estimate, so impressed with Copeland’s appeal and the seriousness of the situation, appropriated five times that amount, and gave the health commissioner $25,000 in emergency funds.12

Unlike the health commissioners of other American cities, Copeland’s strategy for combating the epidemic was not to issue closure orders, but rather to quickly identify and isolate those who fell ill. He reiterated to the public the need to put sick family members in their own room while they recovered and to limit contact with that person for the duration of their illness. Health officials isolated as many cases as they could in city hospital wards. Examination rooms were established at Pennsylvania and Grand Central stations, where a nurse and physician team at each could examine all passengers who arrived feeling ill. Those found to be suffering from influenza were removed to a hospital or put in the care of friends and not allowed to continue on public transportation.13 New York’s schools, which had a long-standing program of child health monitoring and care, were kept open. Under the direction of Dr. S. Josephine Baker, director of the Department of Health’s Bureau of Child Hygiene, school physicians inspected children each morning and sick students were sent home. In school, classes were kept separate from each other, and all students were instructed to go straight from school to their homes at the end of the day and not to mingle or form crowds.14 “We have no intention at this time of closing the schools,” Copeland stated, “as I believe that the children are better protected in the schools than they would be in the streets.”15 New York’s schools remained open for the duration of the epidemic.

By the first days of October, New York’s epidemic started getting under way in earnest. On October 4, physicians reported 999 new influenza cases for the previous 24-hour period, bringing the total number of cases since the start of the epidemic to approximately 4,000. Nearly 700 of those cases were among the city’s schoolchildren. The Brownsville section of Brooklyn was particularly hard hit, and all of the borough’s hospitals were overcrowded. Still, Copeland was sanguine about the situation. Putting these figures in perspective, he told the public that Massachusetts – a state with half the population of New York City – had 100,000 cases of influenza. There was still no need to issue a closure order, he added.16

Yet, Copeland did not stand idly by and watch the epidemic unfold. On October 4, he and the board of health resolved that the epidemic of influenza, “while not alarming at the present moment, necessitates care on the part of the citizens of the City of New York.” In conjunction with business owners, the board therefore enacted a staggered schedule for all stores except those selling food and drugs in the hopes of reducing congestion on public transportation. Businesses that normally opened before 8:00 am or closed after 6:00 pm were not affected. All other stores and offices, however, were required to hold to a new schedule that staggered opening and closing times in fifteen-minute increments. Each of the city’s 46 theaters and movie houses was assigned a specific opening schedule between 7:00 pm and 9:00 pm to spread out the evening entertainment crowds. 17 That evening, the first of a series of explosions rocked the T. A. Gillespie Shell Loading Plant in the Morgan section of South Amboy, New Jersey, across the Raritan Bay from the southern tip of Staten Island. The explosion triggered a fire and more explosions that lasted three days, forcing the evacuation of South Amboy as well as nearby Perth Amboy and Sayreville. In the chaos of the mass exodus, thousands fled their homes, with many traveling to New York for refuge. The next afternoon, city officials closed the bridges and halted subway traffic, leaving thousands to cram aboard the ferries as they fought their way to and from home. On the very day that Copeland intended to begin a program to lessen congestion on public transportation, the Gillespie explosion caused the exact opposite. With little it could do to control the situation, the board of health delayed implementation of the staggered business hours until Monday, October 7.18

Meanwhile, new cases tallies continued to mount: 2,000 on October 9, then 3,100 on October 11, and some 4,300 on October 12.19 Copeland believed that dirty and crowded theaters were a major culprit in the spread of the epidemic, and on October 11 he announced that individual theaters would be allowed to remain open only if they were well ventilated, clean, and did not allow patrons to cough, sneeze, or smoke. A next day, the health department closed several theaters due to failure to meet the new sanitary codes. Several others closed because of low attendance.20

The surging cases taxed the city’s resources, and Copeland realized that he and the health department needed help in combating the epidemic. On October 12, he created a special Emergency Advisory Committee to assist him. Included were representatives of private and public city hospitals, institutional and home nursing, the Red Cross, merchants, social services, the United States Public Health Service, and the city’s Department of Education.21 One of the first orders of business was to divide the city into 45 districts (eventually increased to 150) to help distribute resources.22 As in nearly every community across the nation, the severe shortage of nurses and the care they provided was the most pressing problem. Community organizations across the city pitched-in, organizing volunteer nurses, collected food and supplies for needy families, and offering their automobiles for ambulance services and doctors’ calls. Lillian Wald, pioneer of the visiting nurse profession and champion for health care services for the poor, volunteered her formidable nursing organization, the Henry Street Settlement in the lower East Side of Manhattan, to manage home nursing across the city. The head of Mayor John Hylan’s Committee of Women on National Defense, Millicent Hearst (wife of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst), was appointed chair of a special committee to help coordinate food relief and transportation for visiting nurses.23 The Red Cross, the Henry Street Settlement, the Brooklyn Visiting Nurses Association and several other volunteer organizations organized an Emergency Nurses’ Council to help recruit nurses and allocate medical care, and to organize volunteers for door-to-door canvassing of homes with influenza cases.24 New York University and Bellevue Hospital put their third-year medical students to work as volunteers in the cause.25 Across the city, people and organizations volunteered their services to help bring an end to the epidemic and to alleviate the suffering of the ill.

The epidemic continued to grow worse. On October 19, physicians reported 4,875 new cases of influenza. Some began to grow impatient, and took their frustrations out on Copeland and Mayor Hylan. In Staten Island, several shipbuilding companies reported a 40 per cent drop in productivity due to sick employees unable to show for work. Acting on behalf of the shipyards, Richmond Borough President Calvin Van Name implored Hylan to order Copeland to close Staten Island theaters, saloons, and other places of amusement in the hopes of bringing a swift end to the epidemic.26 Business owners prepared to counter any such move. A few days later, the deputy police commissioner asked Copeland to close movie houses and dance halls on Staten Island.27 One city doctor, a representative of the Medical Society of New York County, complained that the health department neglected to quarantine every passenger on the Bergensfjord when it arrived in August, and instead only isolated the sick crew.28 Former health commissioner and now Superintendant of Mount Sinai Hospital, S. S. Goldwater, protested Copeland’s decision to keep the city’s schools open during the epidemic. He believed that the “paper program,” as he called it, of monitoring students for illness was sound, but that there was “almost criminal laxity” in carrying out the program. As a result, he argued, sick children were not being excluded from school.29

Copeland would not budge. First, he believed that the epidemic would soon crest and then decline. He also believed that the school program was working, and cited evidence indicating that at least half of the absences in school were not due to illness but to overly concerned parents who decided to keep their children home.30 Mayor Hylan stood by his health commissioner. Responding to told Van Name and Goldwater, Hylan stated that he would not meddle with Copeland’s authority. “Dr. Copeland has been placed in charge of the Health Department,” he wrote to Van Name, “and I will not interfere with him at the behest of a former incumbent of the office who is attempting to take advantage of a very grave and serious condition that is a menace to the public health to advertise himself and to encumber the work that Dr. Copeland is seeking to accomplish.”31 Copeland responded to Van Name in a less acerbic tone. Citing death rates from Boston, Baltimore, Washington, DC, and Philadelphia – all cities that had enacted closure orders – Copeland wrote Van Name that New York City had weathered the epidemic thus far with much better results. He added that his department had closely monitored Staten Island’s epidemic and had worked to procure hospital beds, nursing care, and other resources for the community. “It is my judgment that when the history of the influenza epidemic in America is written,” he wrote, “as an official of the City of New York you will not be ashamed of the chapter devoted to the care of this metropolis.”32 Copeland did close several movie houses and dance halls in Staten Island for failing to maintain proper ventilation and sanitary conditions.33 As a nod to local power, he and the board of health amended the New York Sanitary Code to give each borough’s assistant sanitary superintendent the authority to close public places where food and drink were handled or stored if those places were found to be in an unsanitary condition. The board also made coughing and sneezing without covering your nose or mouth a misdemeanor.34

Volunteers, city workers, and health officials continued their work. The volunteers at the Winifred Wheeler Day Nursery at the East Side House Settlement (then located in Manhattan’s Upper East Side) created a day nursery to care for 100 children who could not go home because family members were too ill to care for them.35 Dr. H. G. MacAdam, chief of Department of Health’s Institutional Inspection division, personally took charge of finding lodging for influenza orphans. “I look on myself as the official ‘daddy’ of all these little ‘shavers,’ and will work day and night to see that they do not contract the influenza,” he declared.36 The women of the Emergency Committee and its affiliated organizations worked day and night to organize nurses and relief work. By late-October, these women were feeding and caring for over 3,000 New Yorkers each day.37

Copeland himself worked tirelessly on combating the epidemic, finding hospital beds for patients, ensuring theaters and movie houses were properly ventilated, allocating resources and manpower, and on trying to win over his detractors. With more than 2,000 bodies of influenza victims awaiting burial in Queens, Copeland arranged for 50 city street sweepers to work as gravediggers at Cavalry Cemetery, and had Brooklyn Borough President Edward Riegelmann dispatch an additional 25 men from his borough to assist.38 Eventually, the stress of working round-the-clock for five weeks straight took its toll on the beleaguered health commissioner; he was unable to work on Sunday, October 27 and spent the entire day resting in bed with exhaustion. Copeland was back at work the next morning.39 His son, however, did not fare quite as well. Although he recovered, the 8-year-old fell ill with influenza in late-October. His school, the private Ethical Culture School at 33 Central Park West, had been closed since October 20 because of parents’ and teachers’ fear of influenza. Copeland said this was further proof that children were safer in schools than playing in the streets.40

By November, New York’s epidemic situation had improved sufficiently for Copeland to announce the disbanding of the Emergency Committee and a return to normal operating hours for businesses. On November 1, Copeland met with his Advisory Committee and representatives from the various nursing and relief agencies to receive their final reports and to thank the members for their hard work during the city’s epidemic.41 The next day, he announced that the staggered business hour plan would be removed, and on November 4 the board of health met and resolved to rescind the October amendments to the Sanitary Code. Beginning the evening of Tuesday, November 5, businesses could return to their normal hours.42 Smoking in theaters could resume, but establishments would still be required to maintain proper ventilation and to prevent crowding. Just over 700 cases were reported for the day, a drastic decline from the daily tallies of the previous weeks.43 New York’s epidemic was over.

November was a time for hope and renewal. With the end of the epidemic – although influenza continued to circulate for the next several months – New Yorkers could begin to piece their lives back together. On November 11, city residents celebrated the end of the Great War with wild abandon. In a victory parade, Mayor Hylan led a throng of city employees in a triumphant and jubilant march up Fifth Avenue as celebrants showered them in confetti. Among the marchers were more than 200 men and women from the Department of Health who were applauded by crowd for their role in ending the epidemic. “Look at the bunch that put the ‘flu’ out of business!” was the cheer.44

In an interview with the New York Times printed on November 17, Copeland recounted the story of New York’s recent epidemic and offered his argument for why the city had fared so well while other East Coast cities had been so hard-hit. First, he said, the health department worked to isolate the early cases coming from ships landing at the port. Once cases began to appear amongst the resident population and the disease gained a foothold in the city, the health department turned its full attention to combating the epidemic, organizing several advisory panels and committees and working in cooperation with volunteer organizations to allocate resources, recruit and direct nurses, and relieve the suffering of the ill and their families. Unlike other cities, he said, New York did not issue school closure orders. “They may have been just the right things to do in those places; I don’t know their conditions,” he wrote. “But I do know the conditions of New York, and I know that in our city one of the most important methods of disease control is the public school system.” Three-quarters of New York’s one million schoolchildren live in tenements, he said, where their homes were frequently crowded and unsanitary and where their parents were primarily occupied in putting food on the table and keeping a roof over their heads. Those parents simply could not afford the time or money to provide proper medical attention. It was much better, therefore, to keep the schools open so that children could be monitored for illness by school physicians and nurses.

As for theaters and movie houses, Copeland said that the big, modern establishments were not places that spread influenza. The smaller, hole-in-the-wall theaters that had improper ventilation were problematic, and his department worked hard to close those establishments until the issues could be rectified. Those theaters that remained open were made “centres of public health education” through instructions on proper cough and sneeze etiquette, information on how influenza spreads, and instructions on how to properly treat and recover from the disease. By keeping theaters and places of amusement open, Copeland said, he helped maintain morale and kept the city from “going mad on the subject of influenza.”

Copeland’s greatest anxiety was public transportation, especially subways, which he believed were the most dangerous of all public places because of the tremendous crowding they caused. People who are sick, he argued, do not go to theaters or churches. They do, however, still go to work. Thus, he worked to make sure subways were well ventilated and he asked the board of health to pass the temporary staggered business hour amendment to the city’s sanitary code.

Ending the interview, Copeland compared New York to other East Coast cities. His city had done better than Boston, Washington, Baltimore, or Philadelphia, all places that had issued closure orders. Why? Copeland attributed it to New York’s long history of fine and efficient public health work and to a health department that had worked diligently for the previous two decades to alleviate unhealthy conditions in the streets, tenements, shops, and restaurants. “The fact that the death rate was kept down so low, and that the epidemic did not assume more alarming proportions,” he said, “is a wonderful tribute to the city’s health control in years past.”45 Through the tireless actions of Copeland and his staff at the health department, and through the amazing volunteer work of the city’s relief organizations, New York was able to weather its epidemic with a significantly lower morbidity and mortality rate than other nearby cities. Overall, from September 15 through November 16 – the period of New York’s epidemic – the city experienced nearly 147,000 cases influenza and pneumonia, which resulted in 20,608 deaths.46 These figures gave New York an excess death rate of 452 per 100,000 individuals, the lowest on the Eastern seaboard. Copeland could be proud of his city of the work he did.

Notes

1 “Early Manifestations of Influenza from Transatlantic Vessels Arriving at New York,” Box 146, Folder 1622, Record Group 90 – Records of the United States Public Health Service, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD; “Epidemiology and Administrative Control of Influenza. Address by Louis I. Harris, Director of the Bureau of Preventable Disease, New York City Department of Health, delivered at a meeting of the Eastern Medical Society, Oct. 11, 1918, and published in the New York Medical Journal,108:7 (26 October 26, 1918).

2 “Early Manifestations of Influenza from Transatlantic Vessels Arriving at New York,” Box 146, Folder 1622, Record Group 90 – Records of the United States Public Health Service, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

3 “Quarantine Put in Force to Check Influenza Here,” New York American, 12 Sept. 1918, 1.

4 “To Fight Spanish Grip,” New York Times, 16 Sept. 1918, 16.

5 “Influenza Attacks 13 on Naval Training Ship,” New York American, 17 Sept. 1918, 11.

6 Minutes of Department of Health of the City of New York, 17 September 1918, Department of Health Minutes, Book 13, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY; Sanitary Code of the Board of Health of the Department of Health of the City of New York (New York, 1920), 37-40. The sanitary code was reprinted in 1920 with the revisions and amendments made during the previous several years.

7 “New York Prepared for Influenza,” New York Times, 19 Sept. 1918, 11.

8 “66 Dead of Influenza in Naval Ranks,” New York American, 19 Sept. 1918, 3; “47 New Cases of Influenza are Reported,” New York American, 20 Sept. 1918, 11.

9 “F. D. Roosevelt Spanish Flu Victim,” New York Times, 20 Sept. 1918, 14.

10 “Influenza on Wane in City,” New York American, 21 Sept. 1918, 5.

11 “Find 114 New Cases of Influenza Here,” New York Times, 24 Sept. 1918, 9.

12 “New Influenza Cases in the City Doubled,” New York Times, 28 Sept. 1918, 10.

13 “85,000 in Bay State Ill with Influenza,” New York Times, 30 Sept. 1918, 9.

14 Baker, S. Josephine. Fighting for Life. (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1939), 155-56.

15 “$25,000 Voted to Fight Grip Epidemic Here,” New York American, 28 Sept. 1918, 11.

16 “Spanish Grip Seizes 999 in One Day Here,” New York American, 4 Oct. 1918, 11.

17 Minutes of Department of Health of the City of New York, 4 October 1918, Department of Health Minutes, Book 13, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY.

18 “Revise Timetable in Influenza Fight,” New York Times, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

19 “Spanish Grip Here Jumps 60 per cent,” New York American, 9 Oct. 1918, 11; “157 in 3,077 New Cases of Grip Succumb,” New York American, 11 Oct. 1918, 13’ “Health Board Orders Masks as Grip Grows, New York American, 12 Oct. 1918, 13.

20 Minutes of Department of Health of the City of New York, 11 October 1918, Department of Health Minutes, Book 13, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY; “Fight Stiffens Here Against Influenza,” New York Times, 12 Oct. 1918, 13. Initially, Copeland required that theaters not admit children 12 years of age or younger, but quickly rescinded restriction when it became apparent that most theater managers were following the new sanitary codes. See “Asks Experts’ Aid to Check Epidemic,” New York Times, 13 Oct. 1918, 18.

21 “Asks Expert’s Aid to Check Epidemic,” New York Times, 13 Oct. 1918, 18; Copeland to Lillian Wald, 12 October 1918, Reel 9, Box 11, Folder 5, Lillian D. Wald Papers, New York Public Library, New York, NY.

22 “Will District City in Influenza Fight,” New York Times, 15 Oct. 1918, 10.

23 “Emergent Aid Corps Named to Fight Grip,” New York American, 15 Oct. 1918, 11.

24 “Fight Stiffens Here against Influenza,” New York Times, 12 Oct. 1918, 13.

25 “Copeland Asks Aid in Influenza Fight,” New York Times, 16 Oct. 1918, 24.

26 “Copeland Refuses to Close Schools,” New York Times, 19 Oct. 1918, 24.

27 “Influenza on Wane in Manhattan,” New York American, 23 Oct. 1918, 11.

28 “Influenza Cases Drop 305 in City, New York Times, 21 Oct. 1918, 12.

29 “Asks Expert’s Aid to Check Epidemic,” New York Times, 13 Oct. 1918, 18.

30 “Copeland Refuses to Close Schools,” New York Times, 19 Oct. 1918, 24.

31 “City Reports Drop in Influenza Cases,” New York Times, 20 Oct. 9.

32 Copeland to Van Name, 4 Nov. 1918, Mayor John Hylan Papers, Correspondence Received, Department of Health, Box 72, folder 796, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY.

33 “Grip Wanes, But Copeland Urges Care,” New York American, 25 Oct. 1918, 9.

34 Minutes of Department of Health of the City of New York, 19 October 1918, Department of Health Minutes, Book 13, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY.

35 “Nursery Taken over By Women,” New York American, 25 Oct. 1918, 9.

36 “Dr. MacAdam Now ‘Daddy’ to Well Babies,” New York American, 28 Oct. 1918, 5.

37 “Sunday Grip Aid Given by Women,” New York American, 28 Oct. 1918, 5.

38 Copeland to Hylan, 29 October 1918, Box 72, folder 795, Mayor John F. Hylan Papers, Correspondence Received, Department of Health, Box 72, folder 796, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY.

39 “Dr. MacAdam Now ‘Daddy’ to Well Babies,” New York American, 28 Oct. 1918, 5.

40 “Copeland Satisfied by Influenza Tour,” New York Times, 30 Oct. 1918, 10.

41 “City Epidemic Bans Soon to be Removed,” New York American, 2 Nov. 1918, 11.

42 Minutes of Department of Health of the City of New York, 4 Nov. 1918, Department of Health Minutes, Book 13, New York City Municipal Archives, New York, NY.

43 “Business

44 New York Department of Health, “Our Part in the Victory Parade,” Staff News. 6:12 (1 December 1918), 8.

45 “Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time,” New York Times, 17 Nov. 1918, 42.

46 “Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time,” New York Times, 17 Nov. 1918, 42; Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of New York for the Calendar Year 1918 (New York City: 1919), 210-11.

Click on image for gallery.

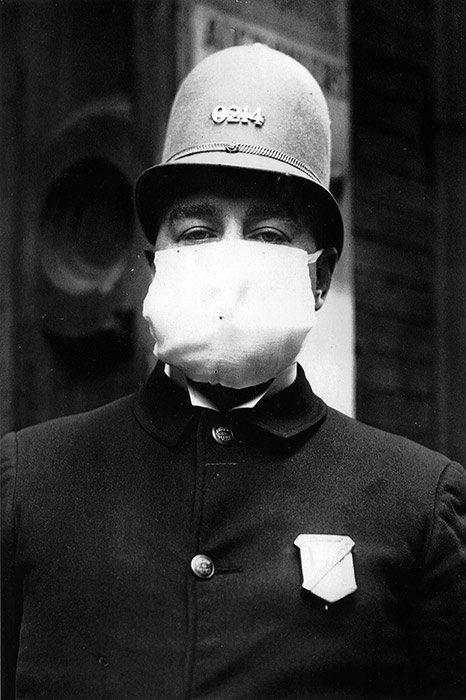

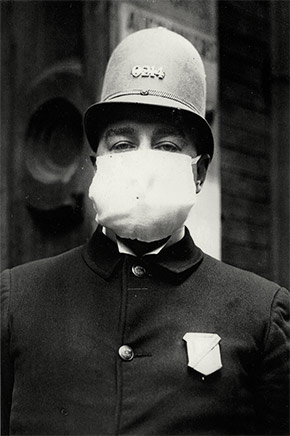

A New York City police officer wears a flu mask while on duty, October 7, 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

A New York City police officer wears a flu mask while on duty, October 7, 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

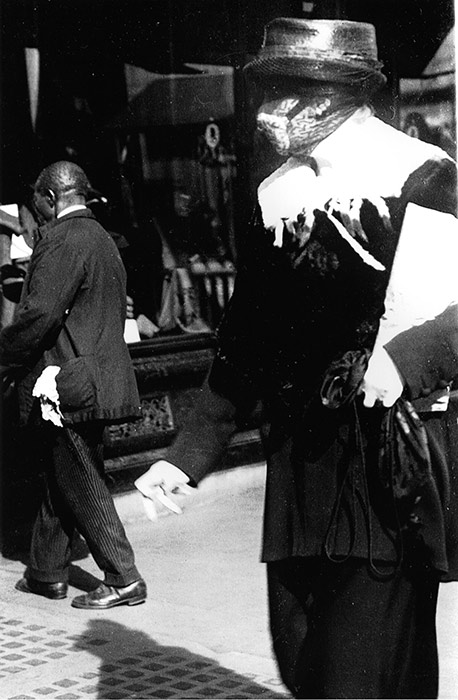

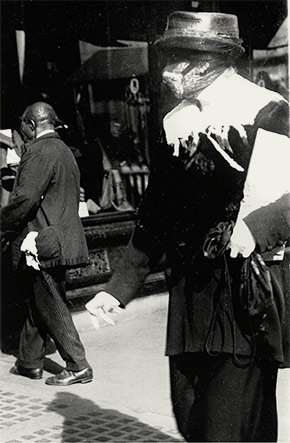

A New York City resident wears a homemade flu mask while out shopping, October 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

A New York City resident wears a homemade flu mask while out shopping, October 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

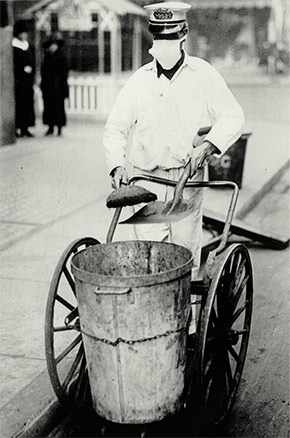

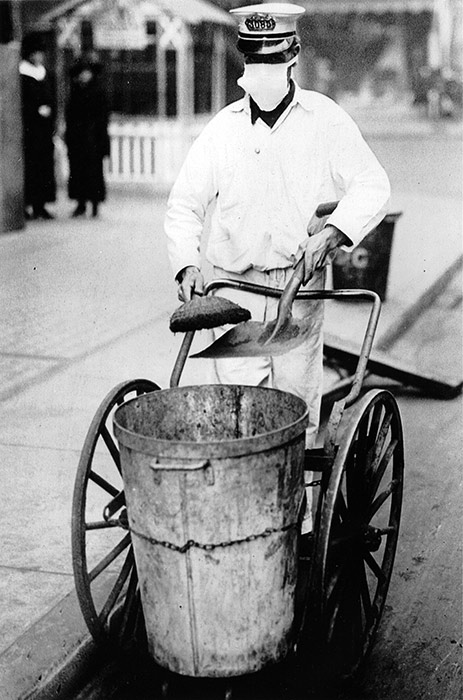

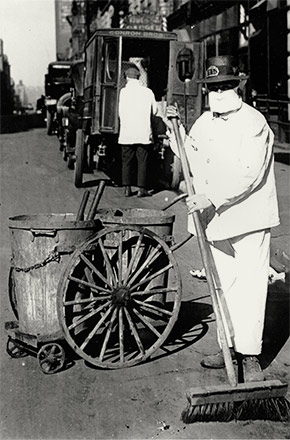

A New York City street sweeper wears a mask while on the job, October 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

A New York City street sweeper wears a mask while on the job, October 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

A New York City typist wears a flu mask while at her desk, October 16, 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

A New York City typist wears a flu mask while at her desk, October 16, 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

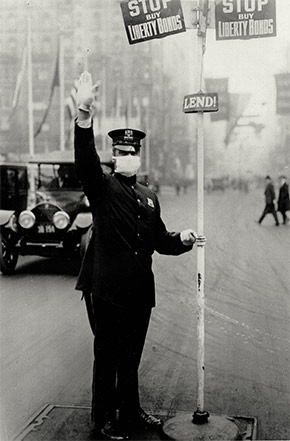

A New York City traffic cop directs vehicles while wearing a flu mask, October 16, 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

A New York City traffic cop directs vehicles while wearing a flu mask, October 16, 1918.