Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Seattle, Washington

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

“In the event the disease appears here, and it is not unlikely that it will, we will endeavor to isolate the first cases and thus try to prevent it becoming epidemic.” Thus spoke Seattle’s second Commissioner of Health, Dr. J. S. McBride, on September 20, 1918.1 Having had time to witness the spread of the epidemic across the United States in the fall of 1918, neither local Seattle nor Washington state officials were under the delusion that the disease would miraculously skip the Northwest. The hope was to isolate the early cases quickly enough to prevent the rapid spread of the disease, thereby keeping influenza from becoming epidemic. If it worked, isolation had the added benefit of precluding closures of theaters, movie houses, poolrooms, and other places of amusement.

For the next two weeks, Health Commissioner McBride and his counterpart in the state Department of Health, Dr. Thomas D. Tuttle, watched the situation carefully, looking for signs of influenza in Seattle. Reports of over 100 cases of “severe influenza” were received from Camp Lewis, located just 45 miles south of Seattle in Pierce County, but the sanitary officer there stated that these cases had not yet resulted in the “Spanish” flu that was affecting the east coast. A few days later, however, camp officials changed their tune, admitting that many of the sick men there were quickly developing pneumonia. Just across Puget Sound from Seattle, mild cases of influenza were reported at the Bremerton naval training station as well as at the yard. In an attempt to protect Seattle’s civilian population from the disease, army officials placed Camp Lewis under quarantine, prohibiting anyone from entering or leaving the camp. Naval officials cancelled all dances and ordered the men to keep way from gatherings of any kind, and shortly thereafter prohibited all visitors at the station.2

McBride had no real way of knowing the extent of the epidemic, since it was not until October 9 that influenza was made a reportable disease. But if conditions in the city had not alarmed McBride, the sudden appearance of a large number of influenza cases in the naval training station at the University of Washington in early-October most likely did. On October 4, city newspapers reported that one cadet had died of influenza and that over 700 more were ill, 400 of them in the hospital under treatment and observation. Still, despite the location of the University within Seattle proper, McBride stated that there were no city cases, claiming that the outbreak among the cadets was only la grippe. The distinction lasted less than a day, after two influenza-related deaths were reported in the city that evening and after state health commissioner Tuttle proclaimed grip and “Spanish” influenza to be one-in-the-same. The next day, after meeting with Mayor Hanson, McBride announced that influenza had made its way into Seattle. He did not stop there, however, and simultaneously prohibited all private and public dances, declared that streetcars and theaters had to be well ventilated, and ordered police to enforce the anti-spitting ordinance with utmost strictness. Tuttle told reporters that the only way Seattle could avoid the same fate as cities in the East was if citizens practiced strict individual voluntary quarantine, having earlier determined that a legal quarantine would be futile. Mayor Hanson added that more widespread closures of public places might be forthcoming if the disease was not quickly checked.3 A few days later, the King County Board of Health issued an order prohibiting all public assemblies within the county.4

These closures were ordered only a day later, on the morning of Sunday, October 6. As the Post-Intelligencer put it, McBride had been “aroused at last to the imminence of the danger facing Seattle,” and was thus spurred to action. Church service was halted, theaters, poolrooms, libraries, entertainment in cafes and restaurants was prohibited, and all businesses allowed to remain open were required to prevent crowding. Public schools were also ordered closed, despite the fact that Superintendent of Schools Frank B. Cooper believed it an unwise move. “I consider it more dangerous to have children running around the streets loose than to have them in school where they will be under strict medical supervision,” he told reporters. Cooper added that he was sorry to see Mayor Hanson getting hysterical over the situation, and that Hanson should have asked for his opinion before he closed the schools, stating that “it is a senseless thing to do.”5

The suddenness of the closure order came as a surprise to all. The Mayor’s office was flooded with calls from clergymen asking if they could hold services. Society women inquired whether planning for their charity events and banquets should continue. Theater owners and managers, while professing a willingness to follow the order, were upset at not having been consulted or even notified sooner of the order. At least one theater operator stated that had the theaters been allowed to remain open, they could have used as the centerpiece of a citywide public health education campaign by showing educational lanternslides on influenza. Now they would be forced to refund the money paid for advance tickets. That afternoon and evening, throngs traveled downtown to enjoy the attractions, unaware of the closure order, only to find locked theater and movie house doors and unlit marquees. One newspaper described the scene as “a mass of humanity, moving aimlessly back and forth.” Among the crowd were hundreds of sailors, despite their orders to avoid gatherings of any kind. The crowd shuffled on to the poolrooms and the natatoriums, only to find those places closed as well. When people tried to find refreshment at the confectionary shops and restaurants, police entered and broke up the crowds. “Any place of business that allows a jam will be closed and kept closed,” threatened the police inspector.6 A few days later, the police chief created a special “Influenza Squad” to enforce the closure order and gathering ban.7

For the next few days, newspapers and the public lambasted Hanson and McBride for issuing the closure order without warning. The Post-Intelligencer made light of the situation in which Seattleites suddenly found themselves. “It was some awful day for the husbands and wives,” stated one article. “Both had to either remain at home or walk the streets.” Actors and actresses were certainly not happy, literally thrown out of work overnight. Not everyone suffered as a result of the closure order, however. The Post-Intelligencer had one fictional young boy proclaim that his mother was happy with the order because it meant his father had to remain at home on a Sunday for a change rather than head to the local watering hole as was his usual custom. Children were said to be cheering all across the city at the unexpected vacation they had received. “Are you the guy that closed the schools?” one little boy asked Mayor Hanson as the latter strode into City Hall. When Hanson replied that he was, the boy told him “Well, say, you’re all right. I’m for you!” The sudden “vacation” was not unfettered, however, as parents were asked to keep their children in their own house or yards. Gas station owners had a banner day; with little else to do, many residents simply hopped in their cars and motored along Seattle’s parkways and out into the countryside. Some pastors, ministers, and priests sidestepped the order by arranging out-of-town services in locales not affected by the church closures.8

At the University of Washington, the influenza situation in the naval training station was said to be much improved, although the rapidity of the turn-around leaves much doubt to this claim. The health conditions in the rest of the university were reported to be very good. Nevertheless, both school and city officials were cautious. They suspended all non-military instruction, requested that all female and those male students not inducted in Student Army Training Corps or Student Naval Training Corps refrain from travel, and asked off-campus students to remain at their places of boarding. Cadets were to be confined to the campus, and all students awaiting induction were told to report to campus to be placed in barracks under medical supervision. All visitors were “requested” to remain off campus; military guards stationed at the entrances would see to it that this request was strictly followed.9 Later, in mid-October, all female and all non-Student Army Training Corps male students were instructed to remain off campus completely until after the epidemic had subsided.10

Hanson and McBride were hopeful that the closure order would have an immediately and salutary effect. Hanson in particular believed that the ordeal would be over shortly. He claimed that many who believed they had influenza really just had la grippe, while others who did have epidemic influenza had it in mild form. With adequate cooperation from the public and with enforcement of the orders by the police and the health department, Hanson and McBride were confident that the epidemic would be over within five days. In an attempt to ensure this, large church weddings and indoor assemblies were added to the list of prohibited gatherings, and private kindergartens were ordered to close.11

Mayor Hanson was of course wrong. In no large city in the United States was the epidemic over that quickly, and Seattle would prove to be no exception. State health commissioner Tuttle was more realistic and less sanguine about the difficult road that lay ahead for Seattle. “Do not mistake the fact that this is a serious proposition,” he told the city. “Any idea that it will last but a short time is ridiculous,” adding that the epidemic would last at least three weeks and more likely a full month. He urged the public to avoid crowds, to get fresh air, and to do away with the mistaken belief that the disease would not strike healthy people. The very next day after Hanson’s optimistic statement, October 8, 125 new influenza cases were reported to health authorities. The disease was now prevalent in all sections of the city. In preparation for the expected influx of more cases, the City Council appropriated $5,000 for epidemic work. The top floor of the old King County Courthouse was converted into an emergency hospital, and arrangements were made to use the auditoriums of larger churches that had well equipped kitchens. Interestingly, McBride told the public that the city would be better served if influenza patients came to a hospital, where the work of the nurses could be carried out more efficiently than it would be in a private home. In other cities, health officers frequently asked people with mild cases to remain at home under the care of a family member, thus freeing up hospital beds and nurses for those who were more severely ill.12

As in most American cities, the local chapter of the Red Cross played a significant role in Seattle’s influenza epidemic. In early October, as the number of new cases began to mount and as the city drew up plans for emergency hospitals, the Red Cross pledged to find nurses to care for the ill and to provide the necessary medical supplies. In fact, the local chapter had already planned for an epidemic relief program even before the orders to do so came from national headquarters. A special influenza committee, headed by the local Red Cross chair Frank Waterhouse, was created to handle the enormous workload demanded by the epidemic and to coordinate efforts with city, state, and federal health officials, and to report on Seattle’s influenza situation to the manager of the Red Cross’s Northwest Division. Despite Mayor Hanson’s order prohibiting crowding, Red Cross workers were allowed to assemble to make pneumonia jackets, face mask, and pillow slips, and every available table at the organization’s Seattle office was being used for this purpose.13

Shipyards, War Work, and Vaccination

With its large shipyards and their importance to war work, Seattle officials were understandably concerned with the effect the epidemic might have on this critical workforce. Seattle shipyard workers accounted for some 30,000 men, nearly ten-percent of the city’s population. McBride knew that it would be difficult to keep this workforce healthy during the epidemic. “With an army of men as large as we have together in the shipyards it is very difficult to keep the disease from spreading should it gain a foothold there,” he told reporters. McBride hoped that, as much of their work was in the out-of-doors, these workers would not be as prone to contracting influenza as factory workers were, but he worried that the men might catch the disease on the busy streetcars they took every day to and from the yards. To protect this “army of men,” McBride proposed the inoculation of each and every one of these workers with one of the several anti-influenza sera that had recently been developed. “Let no question of money or men interfere with your work,” was Mayor Hanson’s response when McBride conferred with him about the plan. In the meantime, as serum doses were prepared in the health department’s laboratory, health inspectors carefully monitored conditions in the shipyards. McBride and Hanson hoped that no serious outbreak of influenza would occur in any of them before enough doses could be manufactured and distributed, but both were prepared to temporarily shut the yards if the situation demanded it.14

By October 11, the city had produced enough doses of the anti-influenza serum to inoculate nearly every shipyard worker. Requests from all across the region came in for the serum, but Seattle officials refused each of them (except for one from Fort Worden, a small army installation at the mouth of Puget Sound). McBride was open in his reasoning: “Seattle needs all the serum we can grow, and we will share with nobody until our shipyard workers and other citizens have been properly inoculated.”15 He was convinced of its effectiveness, citing its successful use at the Bremerton navy yard where only three mild influenza cases had developed among the 3,000 sailors who had been given the injection, and claiming that no one in the city who had been given the two doses of the serum as required had contracted influenza.16

The Case Toll Rises

The serum, like all flu sera and vaccines at the time, did little to halt or even slow the spread of the epidemic in Seattle, and by mid-October nearly 3,500 cases had been reported. McBride, with his high confidence in the serum and in the various anti-crowding measures enacted, blamed private citizens for the outcome. “Influenza is still spreading through the carelessness of persons who insist upon violating the rules laid down to arrest its progress,” he said. State health commissioner Tuttle also blamed citizens, arguing that thousands of people with mild cases were not calling a physician, and instead going about coughing and sneezing and spreading the disease. It is unclear how he thought a physician’s intercession would prevent this. Nor did he explain how Seattle physicians would be able to handle the huge volume of calls they would receive if every person with mild symptoms did in fact contact them. In other cities, residents were specifically asked not to call a doctor unless necessary, and instead to treat mild cases at home. Tuttle did have one point however, namely that doctors could not report cases of which they had no knowledge, and therefore the city and state health departments would have no real way of knowing when the epidemic’s peak had passed. That many counties were filing incomplete reports did not help the problem.17

To drive home the point that the epidemic was serious business, both McBride and Tuttle issued orders for stricter enforcement of public health laws. On October 17, McBride called on Seattle’s Police Chief to arrest and jail anyone caught spitting in public. The next day, he ordered the arrest of the proprietor of any soda fountain, ice cream parlor, or restaurant that failed to use hot water to wash dishes and utensils. At the same time, Tuttle ordered the arrest of anyone caught attempting to hold or participate in a social gathering of any kind. “People who cannot obey the law made necessary in this emergency will be placed where armed officers can compel their obedience,” he announced to residents across the state. In Seattle, local newspapers reported police blotters full of names of those charged with spitting in public and congregating, including twenty-two men arrested for crowding in city pool halls and hotel lobbies. The Police Chief declared that repeat offenders would be dealt with severely.18

The tightened restrictions and the threat of arrest and punishment had an effect, and within a few days the number of people seen in Seattle’s restaurants, poolrooms, and other public places had declined. On October 22, McBride announced that the peak of the epidemic had been reached, and that while the number of deaths would likely continue to rise for the next week or so, the number of new cases would decline. Unfortunately, McBride was wrong. The very next day new case reports showed an increase in the epidemic, and the numbers continued to grow ever larger in the following days. McBride threatened to close all businesses except pharmacies and food stores. Doctors and nurses at the emergency hospital were so over-worked and short-staffed that McBride himself volunteered his services.19

McBride was could not understand why the epidemic had not passed yet, or at least showed signs of decline. The city had done all it could to prevent crowding and public gathering short of shutting down Seattle completely. And that is exactly what he threatened if residents did not to more to help bring an end to the disease. Complaining that people were walking about downtown on the weekends when they should be at home avoiding crowds, he declared that if residents were to stay home for two days it would “do more to stop the epidemic than all the doctors in town.” Failure to check the disease immediately, McBride announced, would result in the same terrible outcome Eastern cities had faced. And he had no intention of letting that occur, he announced, even if it meant resorting to even more drastic measures.20

Seattle Wears Its Masks

McBride made good on his promise the following week. On the morning of Monday, October 28, after conferring with Hanson, the health commissioner issued a sweeping set of additional public health orders, the centerpiece of which was a mandatory flu mask order to go into effect the next day. Anyone shopping at a store, boarding a streetcar, or in any situation where one he or she could come into contact with another person in public was required to wear a mask. Streetcar conductors were told to admit no passenger who was not wearing a mask. Hanson bluntly told commuters that they best get a hold of one of the Red Cross’s 250,000 masks as soon as possible, “or tomorrow morning they will walk to work.” McBride did not stop with masks, however. Making good on his earlier threat, he closed all ice cream parlors and soda fountains in the city until further notice, and forced at least the two-day closure of all shops and stores (except those that sold food or medications) for the weekend of November 2-3. After that, all stores and offices were prohibited from opening before 10:00 am or closing after 3:00 pm, in order to prevent crowding on streetcars during the peak rush hour commute for shipyard workers.21

Announcing the new orders, McBride placed full blame at the collective feet of the city’s residents. The steady increase in cases, he said, was “caused by people themselves refusing to obey the orders of the health department. They will persist in gathering in crowds and seem to feel they individually are immune from influenza.”22 In his mind, the public gathering ban should have worked to stop the epidemic, and its continuation was therefore proof that the people of Seattle were not cooperating. He intended to force this cooperation through even stricter business closures as well as police enforcement of anti-crowding measures. Although the stalls of the city’s Pike Place Market were allowed to remain open for the weekend, McBride warned residents not to crowd the area. “We have given notice that we don’t want the people downtown… and no matter whom it may inconvenience it will be necessary to use the police to keep crowds moving,” he announced. If people needed to buy groceries, they could do so at their local, neighborhood store, he added.23

By the end of the first week of November, McBride began expressing hope that the end of the epidemic could come within a week’s time. On November 8, McBride announced that the closure orders might be lifted with a few days if the situation continued to improve. That, he added, was entirely up to the people of Seattle and their continued observance of the rules. Just as before, he connected the trend in the city’s epidemic to the actions of its residents. This time, however, he praised Seattleites for their strict observance of the new rules, the result of which – according to McBride at least – was the quick downturn in the number of new influenza cases being reported. “We desire, first, to thank the people of Seattle for their co-operation in observing the drastic, but necessary, orders which have been issued by us during the influenza epidemic,” he announced to the public in a distinct change of tone from his statements just a week prior.24

Meanwhile, residents went about their lives while wearing their flu masks. As in other cities that required their use, Seattleites generally disliked the stuffy, hot, uncomfortable apparatuses. The first full day of the mask order, the Daily Times printed a story entitled “Everybody Tries to Look Happy Despite Masks.” The Post-Intelligencer printed a short but scathing editorial poking fun at McBride’s recommendation that masks be made of at least six layers of gauze rather than the usual four. Scientists around the world were baffled by the precise etiological cause of influenza, stated the editorial, but somehow McBride “seems to be possessed of the only fact of his existence, intentions and abilities.” If the flu germ could pass through four layers of gauze, the editorial asked rhetorically, why not six? After all, McBride had no better or more useful information than any of the other physicians, scientists, or public health officials.25 Courthouse record-keepers wondered if flu masks were bad for marriage, since they had witnessed a drastic drop-off in the number of marriage license applications made and a simultaneous increase in divorce filings in the wake of the order.26

At least ten people were arrested on the first morning the order went into effect for not wearing their mask while aboard a streetcar, each of the offenders required to post $5 bail at the Police Court. But because they were legally prohibited from discriminating in taking on passengers, many conductors simply ignored the order that first day. This prompted Mayor Hanson to notify the transit company that the city would take full responsibility for the order and its results. Masks had to be worn, without exception. Several days later, McBride, concerned over reports that customers were not wearing their masks while inside stores, threatened to put a police lock on every shop he found violating the order.27

While most went along with the mask order and a few refused to do so, several entrepreneurial-minded Seattleites found ways to make the most out of the situation. One man, a salesman for the Kaybee Doll & Toy Company in Seattle on business from Los Angeles, found it difficult for customers to warm up to him while he wore his mask. So he had “Buy Kaybee Dolls” printed across his mask, creating a conversation piece that quickly brought him business. The Post-Intelligencer suggested that political candidates use this idea to print campaign slogans across masks.28 Another, more criminally-minded man posed as a police officer – complete with bogus uniform and fake badge – and approached people not wearing a flu mask, giving them the option of either being placed under arrest or paying a $5 fine on the spot. In at least two confirmed cases, the people paid the “fine,” with reports of a dozen more alleged instances.29

The Epidemic Wanes

As the days of early-November continued to roll by, Seattle’s flu situation slowly improved. Nevertheless, McBride and Hanson were reluctant to remove the closure order, let businesses return to their normal hours, or allow residents to remove their masks, however, for fear that the epidemic would take a sudden turn for the worse. “There seems to be no doubt that the situation has materially improved,” Hanson told the public on November 10, but added that he “was not prepared to say just when we can relieve the city of the restrictions” imposed by the health department.30 Theater owners were especially hopeful that they would be allowed to re-open at some point during the week. Their productions had been put on hold for the past five weeks, and players were eager to get back on stage. Some production companies had already made tentative plans to leave Seattle shortly for other locations where theaters were not closed.31 The end of the closure order would only do theater owners any good if they had shows ready to go on-stage when the doors re-opened. No doubt the people of Seattle were as eager to see the shows as theater owners were to put them on stage.

November 11 – Armistice Day – then was cause for double celebration for Seattleites. Abroad, the war against Germany was over. At home, health commissioner McBride announced that evening that the closure orders and gathering bans would be removed at 8:00 am the following morning, with schools to open November 13 (later pushed back one day so that classrooms could be disinfected). Unbeknownst to him, however, Tuttle and the state Board of Health rescinded the mask order just an hour before Seattle’s bans were lifted. Tuttle’s reasoning was that the mask order was practically unenforceable, since most county prosecutors around the state refused to co-operate with the health department.

McBride was upset. Had he known the state was going to do away with the mask order, he said, he would have kept the closures in place. As it was, Seattle officials had little practical choice but to allow city residents to remove their masks. With no backing from the state or from county prosecutors, McBride announced that Seattle’s mask order, too, was unenforceable. The health commissioner worried that the large crowds that had formed to celebrate the armistice and that would likely form again that evening to continue to celebrate and to seek out entertainment after being starved of it for so long would cause resurgence in the epidemic. There was little he could do, though, other than warn residents to avoid crowds. Given the celebratory mood of the city, McBride was fully aware that this was a futile request.32

Throngs of people packed the downtown district, filling theaters to see performances such as “My Soldier Girl” at the Metropolitan and “The Race of Love” at Pantages. For the vaudeville crowd, the Ford sisters, called “the greatest dancing pair on the Orpheum Circuit,” was performing at the Moore. The owner of the Oak Theater had taken the time off during the closure order to renovate his theater, and now looked forward to opening with a musical comedy. Crowds of patrons waited in line at move house box offices, eager to see a show. By noon most movie houses had to warn patrons that theaters were at standing room only, and by that evening the lines stretched for a block from each theater. As the Post-Intelligencer put it, “the public threw its masks in the stove, piled the breakfast dishes in the sink and hit for town on the first available street car.”33

Resurgence?

The large-scale celebrations and the crowding of downtown theaters, cabarets, and movie houses did not seem to have much of an effect on the flu figures, and the numbers of new cases continued to dwindle during the remaining days of November. By early-December, however, the disease seemed to be making a comeback. McBride did not believe Seattle would see the same number of cases and deaths it had during October, but nevertheless he warned the public to be vigilant and to take precautions. The medical inspector for Seattle’s public schools ordered all pupils thoroughly examined, prohibited the assemblage of students, and instructed staff to send any child home who was ill. Children from homes with cases of influenza would not be permitted to return to school for at least ten days, and all absent students would be visited by a school nurse.34

Worried that a second wave of the epidemic was hitting Seattle, on December 2 Hanson and McBride drafted a resolution requiring the quarantine of all suspected cases of influenza and presented it to the city counsel for a vote. Hanson, who had just returned from a trip to Spokane, was particularly concerned by the recurrence of influenza he witnessed in that city. McBride felt the disease was making its way back into the community via outsiders arriving by boat and train. He believed that if these suspected carriers could be quarantined, Seattle might be spared another round without having to resort to a new set of closures. Presenting his case before an emergency session of the City Council on December 5, McBride told members of how fifteen men from cheap lodging houses were recently removed to hospitals. All had been severely ill for several days, but no one had contacted a physician. Under the new rule, the lodging house owners would be required to contact the Board of Health in such cases. The City Council passed the quarantine resolution.35

Health inspectors were soon very busy quarantining homes. By noon the day after the City Council passed the resolution, more than 100 placards had been posted. The health department was quickly flooded with phone calls from physicians and private citizens reporting cases. By December 10, nearly 1,000 placards had been posted on Seattle homes.36 Residents, perhaps worried that the gathering bans and public closures they had come to detest might be enacted again, seemed eager and willing to do anything to help the Health Department rout the disease once and for all. In the public schools, attendance was more than fifty-percent below normal enrollment, in part due to illness but largely because worried parents kept their healthy children home. School officials considered closing the schools completely as a result of the low attendance.37

Ultimately, this proved unnecessary, as the second wave passed by late December. Small numbers of new cases and deaths continued to be reported, and ten patients were recuperating in the city’s emergency hospital as late as February 28. Slowly, however, the epidemic receded and Seattle recovered.

Conclusion

On December 31, 1918, the chief inspector of the Seattle Department of Health’s quarantine division submitted his annual report to McBride (published in 1920 as part of the Department’s 1918-1919 annual report). The chief inspector blamed the spread of the epidemic on several sources. “Handicapped by routine red tape at first, later by the careful physician (careful not to report his cases), the ‘Doubting Thomas’ of the laity, and in many instances by gross neglect on the part of persons having the disease in a mild form, the loss of life, health and happiness has been appalling,” he wrote. His conclusion: that the use of strict quarantine was the only “remedy,” with severe penalties for anyone – physician or lay person – who failed to report cases.38 In short, the chief inspector, like McBride, was quick to blame the people of Seattle for the spread of the epidemic, either overlooking or failing to acknowledge the way the disease had operated in nearly every other American city.

Of all the methods of disease control that Seattle attempted during the influenza epidemic, it is its use of strict quarantine that is perhaps the most interesting. Like Portland, Seattle turned to quarantine during its second wave, when cases once again began to mount and after the city had implemented and then removed closure orders and prohibitions against public gatherings. In Portland, the City Council passed a quarantine order at the behest of the mayor and over the strong objection of the health commissioner. In Seattle, although objection to its use was not terribly strong, quarantine was ordered after state health commissioner Tuttle had expressly announced that it was of little if any use and would therefore not be implemented in the state. There is no evidence that Tuttle attempted to block Seattle’s quarantine order. But the two episodes demonstrate the tremendous pressure that health officials often found themselves under to try anything and everything in their power to stop the epidemic, whether or not they believed those methods even practical.

In Seattle, the raw numbers alone likely caused this pressure. Seattle’s influenza epidemic claimed over 1,400 lives from September 1918 through February 1919, and left the city with an excess death rate of 414 per 100,000.39 Yet, despite this staggering number, Seattle fared well for a city of its size, a testament to the massive death toll the disease caused across the United States. Pittsburgh, by comparison, had a death rate during the same period nearly double that of Seattle. McBride was quick to remind Seattleites that they had fared comparatively better than most of their national counterparts. Statistically, this was entirely true. The statistics, however, were cold comfort to the families and friends who had lost loved ones to the deadly disease.

Notes

1 “Seattle Free of Influenza, But Is Warned,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 21 Sept. 1918, 1.

2 “Denies Spanish Influenza Has Reached Camp,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 29 Sept. 1918, 5, and “Several Deaths From Influenza at Naval Camps,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 4 Oct. 1918, 1.

3 “Seattle Is Ready to Fight Spread of the Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 5 Oct. 1918, 1. In late-September, State Health Commissioner Tuttle had telegrammed United States Surgeon General Rupert Blue, asking for advice on the use of quarantine. When Blue responded that quarantine was not practical, Tuttle declared that the Washington Department of Health would not issue orders to quarantine cases and contacts during the influenza epidemic. See “Gives Warning Against Spanish Influenza Spread,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 26 Sept. 1918, 7, and “State Not to Attempt Influenza Quarantine,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 27 Sept. 1918, 9.

4 “Three Deaths form Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

5 “Ban Gatherings in an Effort to Halt Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

6 “Ban Gatherings in An Effort to Halt Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

7 “Three deaths from Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 9 Oct. 1918, 1.

8 “Gloomy Sunday Is Result of the Influenza Ban on All Places of Amusement,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

9 “Ban Gatherings in An Effort to Halt Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Oct. 1918, 1.

10 “Halt Entrance to ‘U,’” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 19 Oct. 1918, 16.

11 “Four Dead Day’s Influenza Toll,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 7 Oct. 1918, 1; City Hastens to Curb Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

12 “City Hastens to Curb Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 8 Oct. 1918, 1.

13 “Red Cross Making Pneumonia Jackets,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 9 Oct. 1918, 7.

14 “Shipyard Workers to be inoculated with Anti-toxin,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Oct. 1918, 13.

15 “Four Deaths of Influenza in Day,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 10 Oct. 1919, 1.

16 “Three Deaths from Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 9 Oct. 1918, 1, and “Public Urged to Check Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 14 Oct. 1918, 2.

17 “Influenza Cases Mounting Higher,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 15 Oct. 1918, 9.

18 “M’Bride Urges Health Crusade,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 18 Oct. 1918, 2, “Tightening Up on Quarantine Web,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 19 Oct. 1918, 2.

19 “Influenza Gain Brings Threat to Close Many Business Establishments,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 25 Oct. 1918, 1.

20 “McBride Declares Rigid Rules Must Be Made to Curb Influenza Spread,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 26 Oct. 1918, 1, “Seattle Facing Rigid Quarantine,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 27 Oct. 1918, 12.

21 “Seattle Ordered to Wear Masks Beginning Today,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 28 Oct. 1918, 1, “Mayor Puts Lid on City Business to Save Lives,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 31 Oct. 1918, 1, “Wear Influenza Mask or Walk, Mayor Orders,” Seattle Daily Times, 29 Oct. 1918, 1. The day after Seattle issued a mask order, the Washington State Board of Health met and voted on a statewide measure, effective November 4, 1918.

22 “Mayor Puts Lid on City Businesses to Save Lives,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 31 Oct. 1918, 1.

23 “Influenza Death Rate Decreasing,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2 Nov. 1918, 2.

24 “City Expected to be Free of Epidemic Soon,” Seattle Daily Times, 3 Nov. 1918, 1, “End of Epidemic Is Believed Near,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Nov. 1918, 2, “Consider Lifting Ban on Theaters,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 9 Nov. 1918, 2.

25 “Everybody Tries to Look Happy Despite Masks,” Seattle Daily Times, 31 Oct. 1918, 1, “Foiling the Flu Germ,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 30 Oct. 1918, 6.

26 “Psychological Effect of Influenza Upon Mind Muddles Statisticians,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 9 Nov. 1918, 2.

27 “Failure to Wear Masks Causes Arrest of Ten,” Seattle Daily Times, 31 Oct. 1918, 8, “Influenza Epidemic Shows Slight Decrease,” Seattle Daily Times, 5 Nov. 1918, 5.

28 “Salesman Prints Name of Goods on Front of Mask,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 29 Oct. 1918, 2.

29 “Bogus Policeman Mulots Mask-Breaking Victims,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Nov. 1918, 2.

30 “Ban to Continue Without Relief,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 11 Nov. 1918, 11.

31 “Theatre Men Hope to Be Soon Open,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 8 Nov. 1918, 11.

32 “Ban Will be Lifted Here Tomorrow,” Seattle Daily Times, 11 Nov. 1918, 1, “City to Unmask by State Order,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 12 Oct. 1918, 1.

33 “City’s Theaters Open Their Doors,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 12 Nov. 1918, 16, “Theaters Throw Doors Wide Open,” Seattle Daily Times, 12 Nov. 1918, 12, “Seattle Theatres Play to Throngs,” Seattle Daily Times¸13 Nov. 1918, 10, and “Seattle, Now Unmuzzled, Puts in the Day Resting Tired Feet at Movies,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 13 Nov. 1918, 10.

34 “School Rules to Curb Influenza,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2 Dec. 1918, 2.

35 “Want Influenza Quarantinable” Seattle Daily Times, 4 Dec. 1918, 2, “Will Quarantine Influenza Cases,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 5 Dec. 1918, 4, “Council Enacts Influenza Law,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 6 Dec. 1918, 2.

36 “Quarantine of Influenza Starts,” Seattle Daily Times, 7 Dec. 1918, 3, “Influenza Cases All Quarantined,” Seattle Daily Times, 11 Dec. 1918, 15.

37 “School Officials Worried Over Flu,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 12 Dec. 1918, 12.

38 Report of the Department of Health and Sanitation of the City of Seattle, Washington, Embracing the Work of the Department and the Vital Statistics for the Calendar Years 1918 and 1919 (Seattle: Lowman and Hanford Co., 1920), 89.

39 United States Bureau of the Census, Weekly Health Index (Washington, DC: US Commerce Department). See the weekly reports for the period from September 14, 1918 through February 22, 1919.

Click on image for gallery.

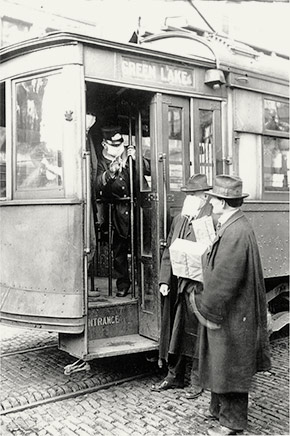

A Seattle Green Lake trolley conductor and passengers with flu masks, October 1918. A little over a year from when this photo was taken, a Green Lake trolley with more than 100 passengers aboard jumped the track, killing one and injuring 70 others. The Green Lake trolley line is now Green Lake Way North.

Click on image for gallery.

A Seattle Green Lake trolley conductor and passengers with flu masks, October 1918. A little over a year from when this photo was taken, a Green Lake trolley with more than 100 passengers aboard jumped the track, killing one and injuring 70 others. The Green Lake trolley line is now Green Lake Way North.

Click on image for gallery.

The 39th Regiment marches down 2nd Ave. with their flu masks on, passing Cheasty’s Haberdashery, ca. October/November 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

The 39th Regiment marches down 2nd Ave. with their flu masks on, passing Cheasty’s Haberdashery, ca. October/November 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

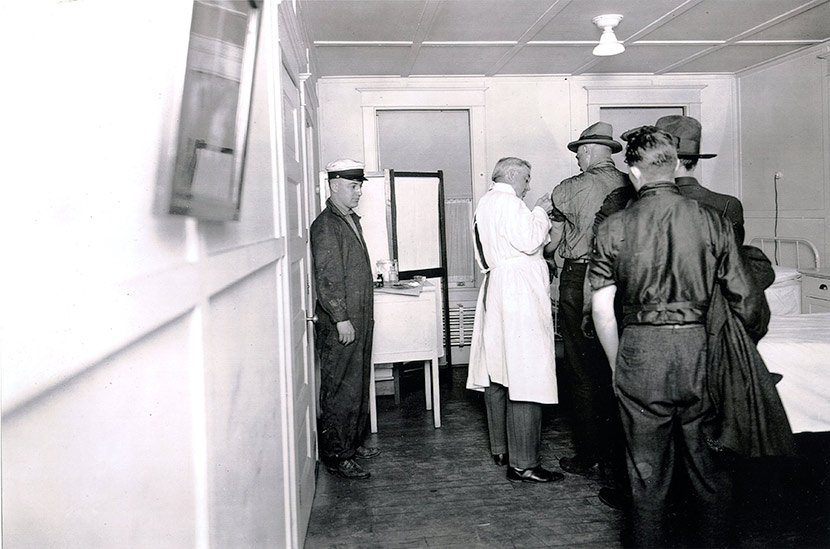

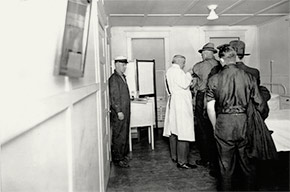

A group of Seattle men line up to receive their influenza vaccines, ca. November 1918. Seattle, like several other cities, placed great emphasis on a public vaccination campaign as a way of halting the spread of the disease. Unfortunately, vaccines at the time were useless.

Click on image for gallery.

A group of Seattle men line up to receive their influenza vaccines, ca. November 1918. Seattle, like several other cities, placed great emphasis on a public vaccination campaign as a way of halting the spread of the disease. Unfortunately, vaccines at the time were useless.