Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Cambridge, Massachusetts

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

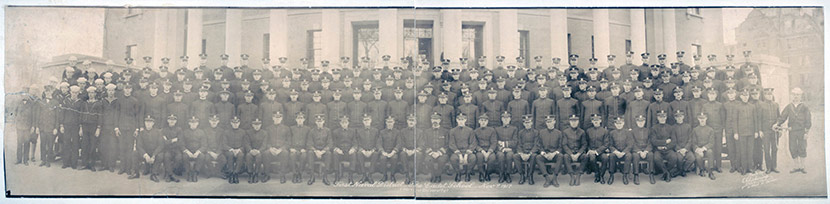

Much like neighboring Boston, located just across the Charles River, Cambridge found itself at the epicenter of the rapidly growing influenza epidemic in the fall of 1918. Surrounded by various military facilities in the greater Boston area and home to two universities–Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology–that served as military training institutions, Cambridge was quickly beset by influenza and pneumonia cases. On September 8, Navy medical personnel placed the Harvard Radio School under quarantine because of the high numbers of cases among the sailors there. The quarantine lasted ten days.1 Within a week, 221 trainees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s naval aviation school had fallen ill with the disease as well.2 By mid-September, hundreds of civilian cases were said to be in the city, with 25 of them already receiving care at Cambridge Hospital. So many nurses there were ill with influenza that, when combined with the influx of cases, the hospital was forced to stop accepting medical and surgical cases for the time being.3 Cambridge’s epidemic was off to a robust start.

City officials took action. First, the Board of Health placed all of its nurses at the disposal of physicians, appointing them district nurses who not only could provide care to the ill but could also act as the eyes and ears of the Board, furnishing it with valuable information about the effects of the disease in the various sections of the city. On September 24, Cambridge school officials met to discuss the situation in their classrooms. Some 3,400 students were reported ill, constituting nearly a quarter of the total enrollment. Officials quickly decided to follow their counterparts in Boston and close the city’s schools. 4 Next, on September 27, the Board of Health declared a state of public emergency and empowered the city’s medical inspector, Dr. Bradford Peirce, to take all necessary measures to combat the epidemic. On October 4, the Board charged Cambridge physicians with reporting all influenza cases by name and address. Initially, the Board hoped to track down cases that had already been treated so that it could determine the extent of the epidemic. With the rush to action and the flurry of activity, however, his task quickly proved impossible.5

Cambridge officials laid out a campaign against the epidemic. The most pressing issue was hospital care for the ill. The milder cases could be left to recover in their homes, but more serious illness required a hospital bed. With a lack of nurses and a shortage of space, however, officials had great difficulty in moving even the most serious cases to area hospitals. After the Board of Health unsuccessfully devoted nearly all of Sunday, September 29 to the duty, it worked to establish a temporary emergency hospital at the Merrill School, newly vacant as a result of the city’s school closures. That evening, with assistance from the Overseers of the Poor department and the city’s Tuberculosis Hospital, and with an ambulance furnished by the police department, the Board of Health admitted several cases of influenza to the new facility. No regular physicians or nurses could be found to take on additional shifts at the emergency hospital, however, and the facility had to be staffed entirely by volunteers, including teachers recently released from their classroom work, off-duty firemen, and others. Shortly thereafter, the Massachusetts Department of Health was able to dispatch several doctors from the Public Health Service Reserve and the Volunteer Medical Reserve to assist at the Merrill School hospital.6

The epidemic continued to grow more severe. At Harvard, university officials tried to keep the campus’s epidemic under control by quarantining the approximately 1,450 men at Harvard College who were part of the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC), and by suspending all classes with 50 or more students as a way of preventing crowding. Clever professors quickly divided their larger courses into several small sections rather than wait until the epidemic subsided to resume their teaching. Initially, the quarantine of SATC cadets–which amounted to a protective sequestration–was rather porous, as only half of the men lived on campus; the other half were required to secure temporary housing in and around Cambridge. On October 7, as military personnel officially prepared to induct the student-soldiers into the Army, these off-campus cadets were assigned to a campus dormitory after first being housed in special quarantine building for three days. There, they were monitored for symptoms of influenza. Men found free of illness at the end of the three-day period were sent to their new dormitory assignments and ordered, as were the rest of Harvard’s SATC units, to remain on campus and out of Cambridge’s shops, streetcars, and other public places. Fourth-year Harvard Medical School students, under the supervision of university Medical Adviser Dr. George Minot, inspected the cadets each morning, sending any questionable cases to isolation immediately.7

On October 4, Massachusetts Governor Samuel W. Mc Call issued a statewide request that mayors and health authorities issue closure orders and gathering bans as a way to help control the spread of influenza. The next day, the Cambridge Board of Health voted to close all pool halls, bowling alleys, ice cream shops, and places serving beverages, and to ban church services. The Board also requested that attendance at funerals be limited to immediate family members only. A few days later, on October 9, the Board added auction rooms to the list.8

The closure order came none too soon. Cambridge officials and volunteers were being inundated daily with calls for aid. Initially, the temporary hospital at the Merrill School operated only out of a few rooms. As more cases poured in, it had to expand room-by-room to accommodate them all. On October 7, with 85 cases already being treated, volunteers there expanded the hospital’s capacity to 105 beds.9 Soon, the entire building was occupied by influenza patients. By mid-October, the facility had become so crowded that the Massachusetts State Guard was called in to erect eight tents in the schoolyard in which to treat additional patients.10 The Columbus Day Nursery offered its quarters on Green Street to be used to house the children of influenza patients while their parents recovered.11 At Harvard, Dr. Minot and his cadre of medical students, along with four physicians from Cambridge, isolated sick student-soldiers and treated some 258 cases of influenza at the university’s Stillman Infirmary. At times, both buildings of the infirmary were filled beyond normal capacity.12

The peak of Cambridge’s epidemic had passed, however, and the situation began to improve rapidly in the second half of October. On October 16, the Board of Health met and voted to remove the closure orders effective at midnight, October 19.13 On October 23, physicians reported only 31 new cases of influenza.14 The next day, the tents in the yard at the Merrill School were dismantled, and the patients being treated there were moved inside the building. Over the next several weeks, as those patients recovered and were released, the schoolrooms gradually returned to their normal state. Cambridge schools reopened on Monday, October 28. The children of Merrill School temporarily were sent to Harvard School until the remaining patients at the emergency hospital could be transferred and the building fumigated.15 On November 6, the last three patients were moved to Cambridge Hospital, and shortly thereafter the Merrill School reverted to its normal function. For all intents and purposes, Cambridge’s epidemic was over. The many nurses and volunteers pitching in to care for the ill and their families were undoubtedly elated. Altogether, they had made 2,527 calls during the epidemic.16

Still, influenza continued to circulate in the greater Boston area throughout the fall and into the winter of 1919. On December 14, for example, Cambridge physicians reported 24 new cases to the Board of Health. By the end of the month, there were a total of 210 cases in the city. The slight spike in cases did not concern the Board of Health, but it gave school officials pause; they decided to extend the Christmas holiday break until Monday, January 6 in the hopes of putting a final end to the epidemic.17 As that date approached, however, the reopening date was extended by a week.18 Schoolchildren were undoubtedly made happy by the news, even if their beleaguered parents were not.

From the time influenza was made a reportable disease on October 4 through the end of 1918, Cambridge experienced 3,014 cases of influenza. Cases continued well into the spring of 1919, although in far reduced numbers and with fewer resultant deaths. By the end of February 1919, Cambridge lost 688 of its residents to influenza and pneumonia. The Merrill emergency hospital admitted 280 cases during its operation, 69 of which died.19 For a city the size of Cambridge, with its population of approximately 109,000 souls, the epidemic took a significant toll. Still, perhaps because of its size, it fared better than neighboring Boston. Cambridge suffered an excess death rate of 541 per 100,000, much better than Boston’s whopping 710.

Notes

1 “Quarantine Raised,” Boston Globe, 19 Sept. 1918, 3.

2 “Grippe Making Great Headway,” 17 Sept. 1918, 1.

3 “Quarantine Raised,” Boston Globe, 19 Sept. 1918, 3.

4 “86 Deaths from Grip Yesterday, Fewer New Cases of Disease Are Reported,” Boston Post, 24 Oct. 1918, 5; “Influenza Adds 109 to Death List in Day,” Boston Globe, 25 Sept. 1918, 1.

5 City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Annual Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Cambridge, MA: 1919), 30-32.

6 City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Annual Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Cambridge, MA: 1919), 30-31.

7 George R. Minot, “An Attempt to Prevent Influenza at Harvard College,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. 179, no. 22 (28 Nov. 1918), 665-67; “Grippe Hits Harvard,” Boston Globe, 1 Oct. 1918, 2.

8 City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Annual Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Cambridge, MA: 1919), 32.

9 “Cambridge Has 12 Death,” Boston Globe, 7 Oct. 1918, 4.

10 “Cambridge Grip Situation Better,” Boston Post, 10 Oct. 1918, 10.

11 “Cambridge Has 12 Death,” Boston Globe, 7 Oct. 1918, 4.

12 Marshall H. Bailey, “Report of the Medical Adviser,” in Official Register of Harvard University: Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College, 1918-19, vol. 18, no. 7 (8 March 1920), 242-43.

13 City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Annual Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Cambridge, MA: 1919), 32-33.

14 “Grippe Deaths in Boston down to 32,” Boston Globe, 23 Oct. 1918, 14.

15 “Cambridge Schools to Reopen Next Monday,” Boston Post, 25 Oct. 1918, 8.

16 City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Annual Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Cambridge, MA: 1919), 30-31.

17 “Schools Will Stay Closed; Cambridge Takes Influenza Precaution,” Boston Post, 29 Dec. 1918, 3; “Funeral Invitations Barred in Epidemic,” Boston Globe, 29 Dec. 1918, 8.

18 “Marked Drop in Grippe Deaths,” Boston Globe, 11 Jan. 1918, 7.

19 City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Annual Report of the Board of Health for the Year Ending December 31, 1918 (Cambridge, MA: 1919), 33.