Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Detroit, Michigan

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

“The quarantine is more a precaution against our men spreading the ailment among the inhabitants of Detroit, which would be aft to happen were they given leave from the station,” United States Navy Commander A. M. Cook told reporters, “than from any apprehension on our own behalf.” Cook was speaking of his decision to quarantine the U.S. Naval Training Station at the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant and shipyard – just six miles downriver from downtown Detroit – after several dozen cases of influenza appeared there. On the evening of September 20, five sailors reported to the dispensary with symptoms of mild influenza. Two days later, that number had swollen to 107.1 Next stop: Detroit.

Health Commissioner James W. Inches was already well aware of the likelihood of influenza coming to his city. On September 18, two days before the first cases appeared at the River Rouge training station, Inches warned Detroiters of the possibility of an influenza epidemic. The city, he said, had experienced an outbreak thirty years earlier (the so-called Russian influenza of 1889) and had dealt with a smaller outbreak the past spring. Now, with serious epidemics already occurring up and down the East Coast, Inches cautioned residents that influenza, although usually a mild disease, could cause death in its more virulent form.2 A week later, after receiving reports from the River Rouge training station about the influenza outbreak there, executive officer of the Michigan state board of health Dr. Richard M. Olin issued a circular to all local health departments asking them to be on the lookout for influenza in their communities. “The army and navy surgeons have matters well in hand,” he told the public to assuage their fears, “and the chances of it coming out to civilians are very few.”3 His statement did not jibe with his actions, however, nor with news from cities such as Boston, now inundated with cases that had first appeared amongst sailors and soldiers. Just to be safe, Olin ordered that all funerals in the state had to be private affairs for the time being.4

Influenza slipped silently into Detroit. On October 1, the city’s first influenza-related death occurred, although it went unreported in the newspapers and Inches made no mention of it.5 It was not until two days later, on October 3, that the Detroit Free Press reported the presence of fifty suspected cases of influenza in the city. Two days after that, there were 135 suspected cases. Inches doubted that any of Detroit’s 185 total cases were all of the “Spanish” variety, and told residents there was no cause for alarm. With prompting from Olin, he did, however, take the precaution of asking school superintendent Charles E. Chadsey to instruct teachers and principals to screen all students for symptoms of influenza and to exclude any that were suspected of having the disease, and asked employers to do the same with their workers.6 He also strongly discouraged residents from holding dances for soldiers and sailors.7

A robust and adventurous man who hunted big game, Inches believed that panic only invited disaster by lowering the immune system to a disease that was otherwise generally mild. Inches therefore enjoined the press to cooperate “in a policy of keeping down public excitement” by downplaying the alarming reports of the epidemic’s destruction coming from the East.8 He advised residents to remain calm, even if they started developing symptoms of influenza. “If you are otherwise in good health,” the told the public, “the changes are 200 to 1 that you will get well and be all right again in a short time.” Go to bed in a warm room, get proper rest, and keep the bowels open was Inches’ medical advice. Still, the health officer was a pragmatic man who realized that a sudden shift in Detroit’s influenza situation might require a change in course. As of now, the city’s epidemic was not serious, he said. If that changed, however, Inches knew that he might be required to close public places – as many other cities already had done – with theaters likely to be among the first on the list. The hardnosed health officer therefore artfully informed theater and movie house owners and managers that it would serve them well to participate in an influenza public education campaign by showing lantern slides about proper cough and sneeze etiquette before each performance. The rest, Inches believed, was up to residents: “It is the patriotic duty of every citizen to make a special effort to keep well and free from colds of any kind and to use all possible influence on other to prevent the spread of an epidemic which has already crippled a part of the country,” he posted in a full-page Detroit News piece.9

Detroit’s epidemic, although off to a slow start, was beginning to grow worse. On October 12, Harper Hospital reported that fifteen of its nurses were out sick with influenza, crippling its ability to treat patients. The hospital cancelled all non-serious surgeries. Nearly 300 new cases of influenza were being reported in the city each day. Inches anticipated a statewide closure order but, after contacting Olin, was informed that such decisions were being left to individual communities for the time being. Slowly, in step-wise fashion, he reacted. First, Inches closed Detroit’s dancehalls, claiming that the close contact of dancers led to an increased risk of spreading influenza. That risk was made even worse, he believed, now that these dancehalls had become overcrowded since the suspension of dances for soldiers and sailors. Next, to prepare the city for what was to come, Inches met with leaders from Detroit’s local chapter of the Red Cross. Together, they laid the groundwork for cooperation between Red Cross and Department of Health nurses, including home visits, food preparation and childcare. Inches then telegraphed Army and Navy officials to request that soldiers and sailors on furlough be kept from entering Detroit. There were, he said, still some 250 cases of influenza at the River Rouge station, and daily these sailors came to Detroit, possibly bringing the disease with them. Next, he asked the Detroit United Railway to close all windows except those near the roof on its streetcars and interurban lines, thus providing adequate ventilation without chilling passengers. Then he canceled a meeting of aircraft workers scheduled to take place the evening of October 12 at the Board of Commerce auditorium to celebrate the completion of the 10,000th Liberty engine, stating that such a large gathering would help spread influenza and thus jeopardize the health of essential war workers. Lastly, Inches warned those with coughs or colds to stay at home and to avoid crowds.10

October 15 saw another 800 influenza cases added to the rolls, the highest number to-date. The total since the start of the epidemic now topped 3,000. Detroit hospitals were overrun with patients; only large hospitals such as Herman Kiefer, which specialized in treating tuberculosis and other communicable diseases, had enough space to take new cases and to isolate them. Many of the new cases were among the indigent, unable to care for themselves or to afford a physician’s fees. With the situation growing more severe, Inches met with the Board of Health to discuss the possibility of issuing a closure order. Reviewing information from East Coast cities, the group, although divided as to whether or not to issue a closure order, ultimately concluded that such action had not slowed those epidemics. Mayor Oscar Marx gave Inches full authority to handle the epidemic any way he saw fit. For now, then, Detroit would remain open, while the sick would be encouraged to stay at home and out of crowds. The city Common Council appropriated $5,000 for the health commissioner to use, promising to make more available as needed.11

Inches turned his attention to the military, which he believed was responsible for bringing influenza to Detroit. On October 12, Inches telegrammed Army Surgeon General William Gorgas to request that the military prevent men from coming to Detroit. “Detroit has one hundred fifty thousand men working on over a billion dollars worth of war contracts. Aircraft, liberty motor, and motor trucks production of the United States depends [sic] upon this city. These men should be as carefully protected as any other part of the country’s fighting force.”12 When his request did not work, Inches took matters into his own hands. On October 17, he notified military officials that all soldiers and sailors would be prohibited from entering the city. To enforce his new rule, he posted inspectors to meet all incoming trains, streetcars, and interurbans and to turn back all those arriving in Detroit except on official business. According to the health commissioner, this was all the action necessary at the moment. In fact, the health commissioner contemplated lifting the ban on public dances, arguing that the educational advantages of keeping places open so that they could be furnished with vital information outweighed the dangers they presented.13 Others agreed with Inches’ general approach. On October 18, representatives from the Red Cross, businesses, and manufacturing, as well as the Board of Health met to discuss Detroit’s epidemic. The group – which included such prominent figures as Cadillac founder Henry Leland, Detroit News publisher George G. Booth, and Alfred L. McMeans of Dodge Brothers – concluded that a closure order would serve no purpose other than to increase hysteria, thereby leading those with common colds and other minor ailments to flock to the city’s hospitals.14

Unfortunately for the group, state authorities disagreed. Later that day, the state Board of Health and Governor Albert Sleeper issued a sweeping order closing all places of public amusement and congregation – with the exception of the schools – effective midnight of Saturday, October 19. The decision came after a heated debate with various local officials, many of whom argued against the order. Dr. Andrew P. Biddle, member of both the Detroit health and school boards, was particularly vociferous in his argument against the closure order. Utilizing rather slippery logic, he argued that, to be effective, the closure order would have to apply to every place where people congregated, including streetcars. “And if you shut off the street cars you will paralyze the city of Detroit,” he exclaimed. Besides, he added, other cities the size of Detroit had issued closure orders to no positive effect. The school issue caused even greater debate, with many present arguing that children were better off remaining in their classrooms where teachers, nurses, and school physicians could monitor them for disease. Ultimately, that issue was left up to local communities to decide. For now, all other places of gathering were closed.15

Inches was not pleased with the decision, but he had no choice but to comply. With the backing of Acting Mayor Jacob Outhard (Oscar Marx was out of town) and with the city’s police department at his disposal, Inches announced to Detroiters that the state ban would be enforced rigidly. In fact, although not listed in Governor Sleeper’s order, police mistakenly shut down ice cream parlors and soft drink shops as well. Inches subsequently clarified that such establishments were allowed to operate as usual. Several Jewish synagogues, misinterpreting the scope of the closure order, held meetings but were notified by police that they would have to shut their doors. For the most part, however, Detroiters readily complied with the ban. Downtown sidewalks were practically empty, although, with few other entertainment outlets and with the six-week ban on wartime gasoline use temporarily removed, the streets were filled with joyriding motorists. Few affected businesses owners grumbled, having anticipated the closure order for several weeks. In fact, some owners expressed relief at being able to cancel costly film and performance contracts, since fear of contagion had led to increasingly empty theaters. Inches allowed some leeway in the rules, allowing, for example, football and baseball games where there were few attendees and where admission was not charged.16

On Monday, October 21, the board of health and school officials met and decided to close all public, private, and parochial schools as of Thursday, October 24. School Superintendent Chadsey estimated that 15% of the city’s approximately 100,000 students were out sick or being kept at home, thus interfering with the ability of schools to complete their educational mission. In addition, the schools employed over 3,000 teachers, a force Inches hoped to use as volunteer health department aides. Operating out of school buildings that could be used as the headquarters for “health zones,” Inches proposed using teacher volunteers to make home visits to investigate cases of influenza and pneumonia.17 In order for this to happen, schools would have to close first. The health commissioner also announced restricted hours for stores and businesses in order to reduce rush hour congestion on public transportation. Those stores and shops that regularly closed during the rush hour period would now have to close at 4:30 pm.18

The health department went to work straightaway. Under the direction of Grace Ross, chief of the health department nurses, Detroit teachers were organized into brigades and assigned to one of the 200 health districts created across the city. On Friday, October 25, many (although not all) of Detroit’s teachers reported to their classrooms for training in their new volunteer positions. Male teachers were tasked with clerical duty at the department of health and at the schools, while female teachers were instructed on how to conduct home visits, how to report their findings, and how to best educate families on proper influenza care. Armed with one day of training, they were sent out to begin their work the next morning.19

Not everyone was happy with the plan. Board of Education member Dr. John S. Hall protested vociferously. For one, he complained, Inches once had argued that keeping schools open meant children would be safer, as teachers and school nurses could monitor them. Now the health commissioner was making the opposite argument, that children were safer out of doors rather than cooped up inside classrooms. More disconcerting to Hall was Inches’ proposed use of teachers as volunteers, which Hall believed would place them in undue danger. Inches responded that he was not asking teachers to act as nurses but rather as investigators, and that their safety would be of paramount concern. Hall refused to buy it.

The teachers in our schools have not been trained as nurses. Many of them will have to go into the homes of some of our poorer classes and take a hand themselves to see that things are done right. They do not know how to do it. It takes three years to train a nurse, and you expect a teacher to do it in one day. More than that, she stands a risk of taking infection herself.20

Many teachers were upset with Inches as well. One such educator sent a letter to the editor of the Detroit Free Press excoriating Inches and the school board for pressing teachers into service as volunteers. None of these officials, she complained, had made provisions to care for or pay the salaries of those who contracted influenza as a result of their work. Furthermore, school officials had conveniently left themselves off of the volunteer rolls. If teachers were expected to volunteer, she wrote, then school officials should be called upon to work as doctors’ aides. “For men who will remain in their germless offices to send word that 3,000 teachers are to volunteer to go into the homes of the influenza patients as nurses’ aides seems like straining the quality of mercy to its limit.” She wryly added that teachers “eagerly scan the morning paper to find out what else they have volunteered to do.”21 Despite these and other protests, the schools remained closed and the teachers continued their volunteerism.

Just as teachers began their new home visit work, the epidemic appeared to be on the wane. On Sunday, October 27, with 615 new influenza cases reported for the day, Inches announced that Detroit had passed through the crest of the epidemic. Whether because of the latest influenza figures or because of the verbal flogging he had been receiving from detractors, he added that the need to have a force of teachers working as volunteers for the cause was now over, after only one day on the job. Schools, he said, might be reopened as soon as October 30. Removal of the other bans would have to wait for Governor Sleeper’s approval, which Inches said he would seek if the situation continued to improve.22 State health commissioner Olin advocated moving slowly to ensure that the proverbial coast was truly clear; he stated it would be at least two more weeks before Michigan communities could reopen their public places. Business proprietors and theater owners bemoaned the closure order, having lost thousands dollars as a result of the public health edicts. The total loss for theaters was said to be in the six-figure range and climbing. Several Catholic bishops and Protestant reverends attempted to persuade Olin to allow them to hold shorter services, to no avail.23

Detroit’s epidemic seemed to be coming to quick end. Inches and school officials announced that the teacher brigades could end their work on October 31 and begin preparing for the reopening of schools on Monday, November 4. On November 1, only 429 new cases were reported to the health department. The improved situation prompted Mayor Marx to ask Inches to make a personal appeal to Governor Sleeper to have the bans removed. Marx insisted that Detroit be allowed to reopen its public places, arguing that the epidemics along the East Coast were far worse and yet those cities were under much less onerous restrictions. He was correct in the first instance, but incorrect in the second; with the notable exception of New York City, the public health edicts imposed upon the Motor City looked much the same as nearly every other city in the United States. This detail notwithstanding, Detroit officials nevertheless believed the time had come to allow their city to return to normal business. Inches made the appeal.24

Governor Sleeper refused. The epidemic was still raging in many other parts of the state, and, according to state Attorney-General Alexander J. Groesbeck, giving Detroit special consideration would be illegal. Grand Rapids, Bay City, Saginaw, and several other cities lodged formal protests with the governor’s office against Detroit being allowed to open ahead of the rest of the state. Sleeper faced two options: remove the statewide ban and risk the lives of residents across Michigan, or keep it in place and risk angering Detroit. He chose the latter. Inches and Marx, although disappointed, agreed with the ruling. “We have no right to demand favors that might cause trouble in other communities,” Inches said in response to Sleeper’s decision. The health commissioner did allow stores to return to their normal business hours, effective immediately.25

During the conference with Detroit officials, Sleeper stated that, if the trend across the state continued, the order might be removed within a week. He kept to his word. On November 3, he told reporters that the ban might be removed as early as Thursday, November 7. Until then, he asked everyone to be patient. Two days later, on November 5, Inches announced that he had received permission from Sleeper to remove the closure order in Detroit. He immediately convened the Board of Health, which voted unanimously to reopen Detroit the next day. Finally, Detroiters would have their entertainments back.

Except that Inches was mistaken. Sleeper contended that he gave Detroit no such permission to reopen, and instead only granted Inches authority to allow an upcoming Christian Scientist meeting to be held. For his part, Inches insisted that he was perfectly clear with Sleeper and did not seek – and subsequently receive – permission for a single meeting but for the complete removal of all the bans. Nevertheless, Sleeper relented. If Detroit wished to reopen, state officials would not interfere, as the Governor had intended to lift the order with a day or two anyway. Inches apologized for the miscommunication, blaming it on a poor telephone connection.26 Detroit went ahead with its plan to lift the closure order and gathering ban effective the morning of Wednesday, November 6. Theater owners were particularly thrilled, and lost no time in readying their businesses for patrons.

The epidemic subsided over the course of November, but returned with some vigor in the early days of December. Inches reassured Detroiters that the recent crop of cases was nothing more than the result of people standing outside in the cold and rain to watch the Thanksgiving Day parade. He did not anticipate a second closure order.27 Olin and Sleeper were of a similar mind. When the preliminary results of a statewide Red Cross canvass indicated that influenza was once again on the rise in many communities, Olin and the state Board of Health only ordered that all homes of influenza patients be rigidly quarantined. The penalty for breaking quarantine was a stiff one: a fine of up to $100 or 90 days in jail.28

Throughout the rest of December and well into the winter of 1919, influenza continued to circulate in Michigan. Olin complained that the outbreaks were the result of people disobeying the quarantine order, arguing that “where quarantine is observed there is no doubting the fact that the cases are receding.”29 Detroiters, however, did not pay the situation much mind. Newspaper coverage of influenza and pneumonia dwindled as Motor City residents returned to life as it was before the epidemic.

Conclusion

Between the start of the epidemic on October 1 and its end on November 20, there were 18,066 cases of influenza reported to Detroit’s Department of Health. Of these, 1,688 died from influenza or its complications. Another 10,920 cases came in January and February of 1919, when the disease made a significant comeback and physicians once again began reporting cases.

All the while, Inches maintained that the closure order in Detroit caused more injury to business interests and caused more panic than it did good. Comparing figures from major cities, he argued that a significant and immediate spike in cases followed in every city that had issued a closure order. Inches attributed this effect to the hysteria closure orders caused, which in turn lowered resistance to disease. He conveniently ignored the fact that he had urged the closure of Detroit’s schools, after initially having argued for their remaining open. Apparently, school closures did not cause hysteria, as Inches spent the rest of the fall of 1918 lauding the plan. He argued that closing the schools to create an army of nearly 2,000 volunteer teachers was a brilliant move.

To be sure, these volunteer teachers were courageous. Asked to help their city, over 1,600 of Detroit’s educators did so without hesitation. Together, they made 102,000 calls in their four short days of volunteer work, reporting on 15,647 cases of illness and discovering 434 families in need of medical care or food or material aid.30 Although it is impossible to say whether these cases would have been aided through other channels if teachers had not volunteered, their work undoubtedly helped the city. That work, however, came at a significant cost, of which Inches never made mention. First, it greatly angered several school officials as well as teachers. Then there was the price tag of the school closure, which at least one school board member pegged at a whopping $30,000 per day.31 Had Inches closed Detroit schools because of their high absenteeism or to help protect the city’s children from influenza, perhaps no one would have questioned the movie. As it was, however, Inches was forced to walk a narrow and rather untenable line of his creation: closure orders caused more disease than they prevented and cost too much, while, in the case of schools, they simultaneously helped the city prevent deaths by creating a corps of “free” volunteers that cost Detroit tens of thousands of dollars.

In January 1919, James W. Inches resigned his post as Detroit’s health officer to become its police commissioner under Mayor James Couzens, a position he held until 1923. By all accounts, he was an able administrator, successfully overseeing the relocation of the police department to new headquarters while dealing with the rise in crime caused by being a border city during Prohibition. Perhaps telling, it is for this position that history mostly remembers him.

Notes

1 “Spanish Influenza Hits River Rouge,” Detroit Free Press, 23 Sept. 1918; Medical Officer US Naval Training Camp Detroit to Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, “Memo, re: Preliminary Report of Influenza Epidemic, 25 Sept. 1918, Box 588, Folder 130212 D-9, Entry 12, General Correspondence March 1912 – December 1925, Headquarters Records, Record Group 52: Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

2 “City is Warned of Influenza,” Detroit News, 18 Sept. 1918, 1.

3 “State Leading Influenza War,” Detroit Free Press, 24 Sept. 1918.

4 “Epidemic Victims’ Burial is Private,” Detroit Free Press, 29 Sept. 1918.

5 Bulletin of the Detroit Department of Health, vol. 11, no. 5 (Nov. 1918), 2. “City Has 135 Cases of Mild Influenza,” Detroit Free Press, 5 Oct. 1918; “Influenza Warning to School Principals,” Detroit Free Press, 5 Oct. 1918.

6 “Germ of Spanish Grip New Arrival in Town,” Detroit Free Press, 3 Oct. 1918;

7 “Influenza Halts Soldiers’ Dances,” Detroit Free Press, 6 Oct. 1918.

8 Bulletin of the Detroit Department of Health, vol. 11, no. 5 (Nov. 1918), 7.

9 “Spanish Influenza,” Detroit News, 8 Oct. 1918, 15.

10 “City’s Dances Closed by Grip,” Detroit News, 10 Oct. 1918, 1; “Churches and Theaters Not to be Closed,” Detroit Free Press, 12 Oct. 1918; “Order Closing Churches Near,” Detroit News, 12 Oct, 1918, 1; “Chiffon Veil ‘Gas’ Mask for Sneeze,” Detroit Free Press, 16 Oct. 1918.

11 “Public Places to Keep Open; 800 New Cases,” Detroit Free Press, 16 Oct. 1918.

12 James W. Inches to United States Surgeon General William Gorgas, 12 Oct. 1918, Box 219, Folder 710 “Detroit, Michigan,” Entry 31E, Record Group 112 – Records of the United States Surgeon General (Army), National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

13 “823 New Cases of Influenza,” Detroit Free Press, 18 Oct. 1918.

14 “Be Calm, Cool; Check Disease,” Detroit News, 18 Oct. 1918, 1.

15 “State Grip Decree: Close up Detroit,” Detroit Free Press, 19 Oct. 1918.

16 “City will obey influenza ban,” Detroit Free Press, 20 Oct. 1918;“City Shut up By Influenza, Detroit News, 20 Oct. 1918, 1; “Michigan Observing First Churchless Sunday,” Detroit News, 20 Oct. 1918, 12; “Detroit Obeys Influenza Ban on Initial Day,” Detroit Free Press, 21 Oct. 1918, 1.

17 “Schools Close as Influenza Plague Gains,” Detroit Free Press, 21 Oct. 1918.

18 “Urges Doctors to be Cautious,” Detroit News, 23 Oct. 1918, 1.

19 “Teachers Will Fight Epidemic,” Detroit News, 22 Oct. 1918, 1.

20 “Plague Crest Perhaps Past, Thinks Inches,” Detroit Free Press, 26 Oct. 1918.

21 “Use of Teachers as Nurses Decried,” Detroit Free Press, 28 Oct. 1918.

22 “Schools May be Open Again by Wednesday,” Detroit Free Press, 27 Oct. 1918.

23 “End of Ban Sought as Epidemic Wanes,” Detroit Free Press, 31 Oct. 1918.

24 “Marx Urges that City be Reopened,” Detroit Free Press, 1 Nov. 1918.

25 “State to Open within a Week,” Detroit News, 2 Nov. 1918, 9.

26 “’Ban Off,’ Says Inches; ‘No Sir,’ Avers Sleeper,” Detroit Free Press, 5 Nov. 1918; “Governor Permits Rescinding of Ban,” Detroit Free Press, 6 Nov. 1918; “State Closing Ban Lifted for Friday,” Detroit News, 7 Nov. 1918, 10.

27 “Slight Influenza Gain Attributed to Parade,” Detroit Free Press, 4 Dec. 1918; “Influenza Gain Not Alarming,” Detroit Free Press, 7 Dec. 1918.

28 “Rigid Quarantine for Grip Ordered,” Detroit Free Press, 11 Dec. 1918.

29 “Christmas Sequel May be More Grip,” Detroit Free Press, 27 Dec. 1918. See also “Grip Again Perils State, Is Warning,” Detroit Free Press, 25 Jan. 1919.

30 Bulletin of the Detroit Department of Health, vol. 11, no. 5 (Nov. 1918), 2-7.

31 “Plague Crest Perhaps Past, Thinks Inches,” Detroit Free Press, 26 Oct. 1918.

Click on image for gallery.

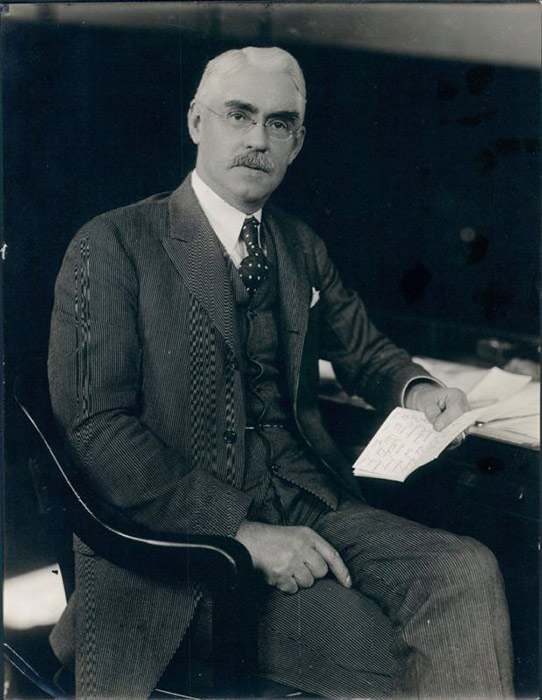

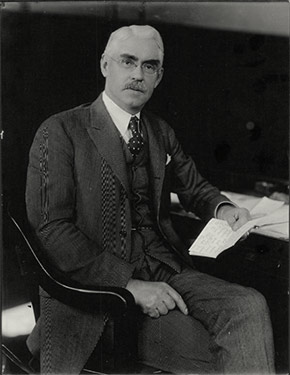

Detroit health commissioner James W. Inches. Before becoming Detroit’s chief health officer, Inches served five terms as the mayor of St. Clair, Michigan. In January 1919 he accepted the post of Police Commissioner. In 1923, he ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Detroit.

Click on image for gallery.

Detroit health commissioner James W. Inches. Before becoming Detroit’s chief health officer, Inches served five terms as the mayor of St. Clair, Michigan. In January 1919 he accepted the post of Police Commissioner. In 1923, he ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Detroit.

Click on image for gallery.

Motor Corps ambulance driver from the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross.

Click on image for gallery.

Motor Corps ambulance driver from the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross.

Click on image for gallery.

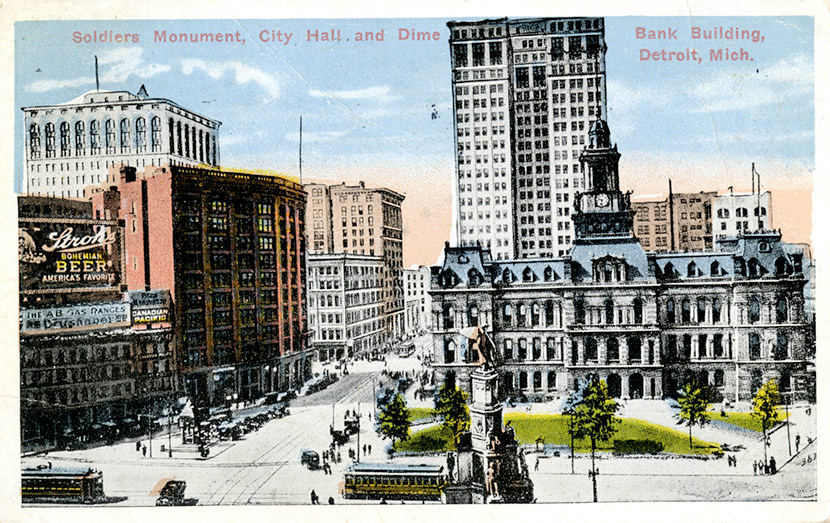

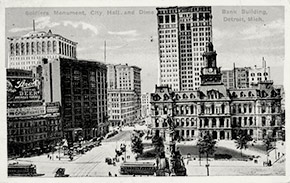

A view of Soldiers Monument, old City Hall, and the Dime Bank Building in Detroit’s financial district. Soldier’s Monument still stands at the southeastern edge of Campus Martius. The old City Hall building was demolished in 1961. The Dime Building is now known as Chrysler House.

Click on image for gallery.

A view of Soldiers Monument, old City Hall, and the Dime Bank Building in Detroit’s financial district. Soldier’s Monument still stands at the southeastern edge of Campus Martius. The old City Hall building was demolished in 1961. The Dime Building is now known as Chrysler House.

Click on image for gallery.

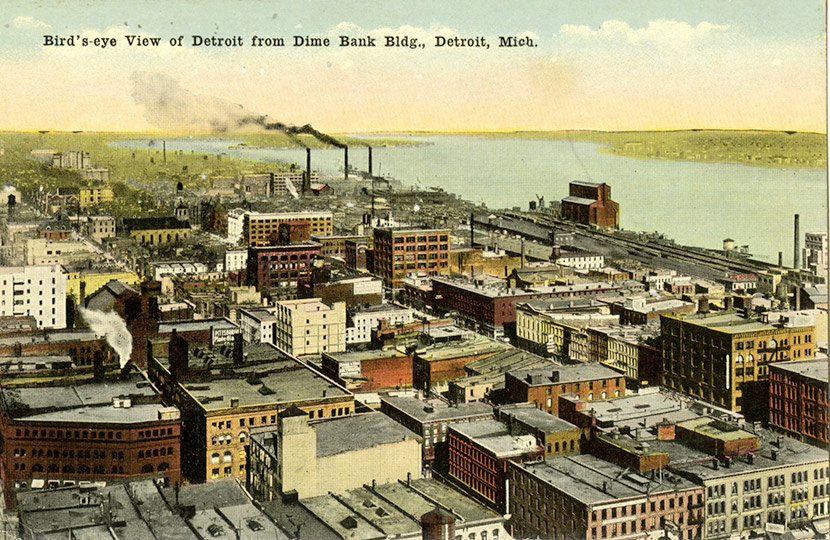

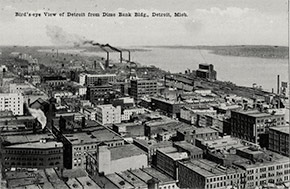

The view from Detroit’s Dime Bank Building (now known as Chrysler House), with the Detroit River and Belle Isle in the distance.

Click on image for gallery.

The view from Detroit’s Dime Bank Building (now known as Chrysler House), with the Detroit River and Belle Isle in the distance.

Click on image for gallery.

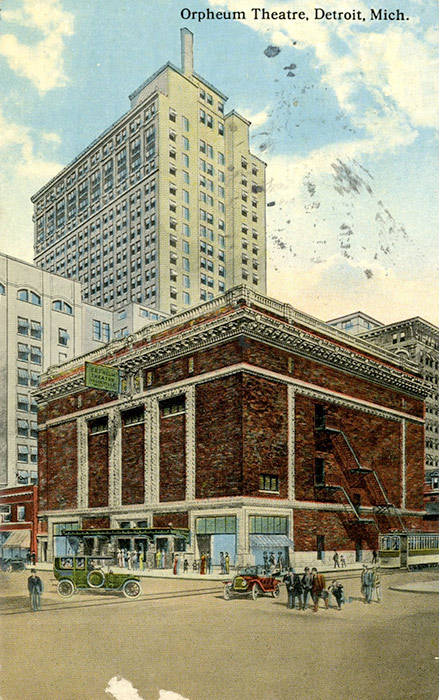

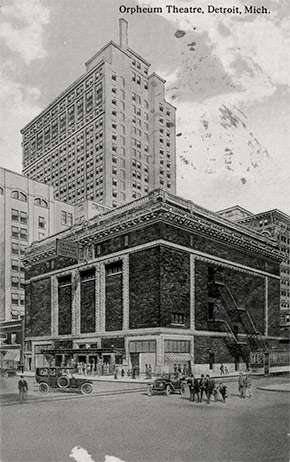

Detroit’s Orpheum Theatre, located at the corner of Lafayette and Shelby Streets. The theater had a seating capacity of 2130 patrons. Like all public venues, it was closed during the epidemic. Known variously as the Orpheum, the Shubert, and the Lafayette during its lifetime, the elaborate Italian Renaissance building was demolished in 1964.

Click on image for gallery.

Detroit’s Orpheum Theatre, located at the corner of Lafayette and Shelby Streets. The theater had a seating capacity of 2130 patrons. Like all public venues, it was closed during the epidemic. Known variously as the Orpheum, the Shubert, and the Lafayette during its lifetime, the elaborate Italian Renaissance building was demolished in 1964.