Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Louisville, Kentucky

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

In the late summer and early fall of 1918, the many military installations across the United States tended to be hit first and hardest with epidemic influenza. Soldiers, sailors, and Marines on liberty, leave, or official business traveled to cities, often bringing influenza with them. This had been the case in Boston, for example, a city ringed with numerous military bases and training facilities.

Just a few streetcar stops down the line from Louisville was Camp Zachary Taylor. The camp was enormous, encompassing 1,530 buildings sprawled across 3,376 acres and accommodating over 45,000 enlistees and officers. At the time, it was the largest World War I Army training camp in North America. On September 24, local Louisville newspapers reported over one hundred soldiers at the camp were ill with influenza. Just a day later, that number had more than doubled to 262. By the end of the month, the camp hospital was caring for more than 2,100 cases of influenza. The hospital was so overcrowded that 15 barracks of the “C” Section – a section of camp located east of the Lincoln Avenue overpass – had to be converted to temporary hospital wards.1

Camp officials acted as quickly as they could to contain the disease. On September 27, they enacted a partial quarantine of the camp, prohibiting the soldiers from entering theaters, movie houses, restaurants, and other public places in town. They also prohibited the soldiers from congregating within the camp. Only a dozen soldiers were allowed in the canteen at a time.2 A few days later, military officials posted provost guards at strategic Louisville locations to prevent soldiers from entering public areas of the city.3

To further protect Louisville, officials from the Army, the United States Public Health Service, and city health officer Dr. T. H. Baker met on September 26 to develop a plan of action. All agreed that the main problem was that of soldiers spreading the disease to the civilian population. That issue was already addressed by the quarantine at Camp Taylor. To further keep civilians safe, the men agreed to try to prevent overcrowding and poor ventilation in Louisville’s streetcars and public places. Health Officer Baker and USPHS officer Lieutenant R. B. Norment asked movie house managers to prevent congestion and to ventilate thoroughly their theaters between films, and asked the Street Railway Company to keep the windows in their streetcars wide open at all times. Further, Baker issued a prohibition against public funerals in order to prevent an assembly of people, several of which would likely have had contact with the disease.4 The next day, Baker and Norment advised residents to walk rather then take streetcars, to stay home if they felt ill, and to avoid crowds. Physicians were told to report cases of influenza to the Louisville health department.5 On October 2, Dr. Joseph N. McCormack, Secretary of the state Board of Health, made influenza a reportable disease across Kentucky and ordered local boards of health to placard and quarantine any infected households for a minimum of ten days.6

Influenza was already circulating amongst Louisville residents. By September 20, a week before these measures were put into effect, some 50 civilian cases had been reported to the health department, although health officials would only confirm that three of them were actually “Spanish” influenza.7

By October 7 it was clear that Louisville’s nascent influenza epidemic was spreading. Norment, now Acting City Health Officer while Baker was on medical leave, directed the city’s district, tuberculosis, and health department nurses to begin preparations for the likelihood of a more widespread civilian epidemic. The most immediate need was for automobiles to help visiting nurses make speedy responses to those in need. The Motor Service League turned to the women of Louisville, who responded generously with their automobiles; on weekends, nurses used municipal vehicles.8

Louisville’s charitable nursing associations organized home care for the city. On the morning of October 7, the Babies’ Milk Fund Association and the King’s Daughters’ District Nurse Association (which would merge in 1919 to become the Public Health Nurses’ Association), and the Board of Tuberculosis agreed to coordinate nursing care through the District Nurse Association. Starting the next day, supplemental nurses worked alongside Louisville’s regular district nurses to care for influenza victims in their homes. Until the number of new cases became overwhelming, nurses conducted all investigations and placarded homes. As the number of emerging cases accelerated, the police stepped in to do the placarding.9 The Red Cross Home Service, Associated Charities and, eventually, the Emergency Hospital, worked effectively to supply meals for the sick. Writing in Public Health Nurse, a Louisville visiting nurse superintendent later praised the cooperation that took place among the city’s private and public health agencies – it occurred “without one hour lost in friction or needless argument.”10

On the same day that Acting Health Officer Norment met with visiting nurses, state Board of Health Secretary McCormack issued a state-wide order closing all churches, schools, and places of amusement or assembly until further notice. Louisville Mayor George W. Smith issued a statement endorsing the state order and putting it in full effect in his city.11 To augment the efforts, Norment met with Louisville’s Retail Merchant’s Association to stagger the work hours of store employees as a way of relieving crowded streetcar conditions.12

On October 12, the health department reported that a total of 2,300 cases of influenza had appeared since September 28.13 Louisville’s citizens moved to help, volunteering even more automobiles to the Women’s Service League and Louisville Automobile Club, in turn permitting visiting nurses to increase their home visits.14 By the end of the month, nurses made a staggering 2,589 calls, routinely working seven days a week to ensure that all who needed it received care.15 Even Acting Health Officer Norment made use of volunteer transportation. He and his assistants drove house-to-house one Saturday, distributing pamphlets on influenza.16 The Louisville Advertising Club agreed to work with a special state committee to provide daily public education in the state’s newspapers.17 Later, when Christmas approached, merchants voluntarily restricted some of their seasonal promotions and implemented other changes to minimize crowds.18

As the epidemic gained in intensity, hospitals soon were stretched to the breaking point. The health department interceded by opening a 75-bed emergency hospital at the Hope Rescue Mission on October 13, under the direct supervision of acting health officer Norment. The emergency facility had the capacity to expand to 110 beds, which it did just days later. Volunteers, including some public school nurses, labored so tirelessly to help patients – many of whom were picked up half dying from the streets – that medical staff sometimes forced the volunteers to stop and rest for their own welfare.19

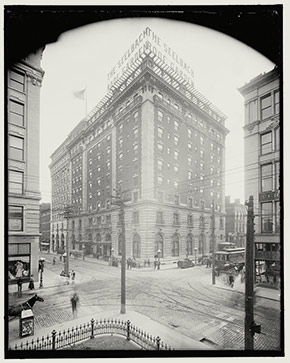

Then, suddenly, the number of new influenza cases started to drop, prompting some to surmise that the epidemic would soon come to an end. On October 18, members of the state Board of Health, the United States Public Health Service, military authorities, and a number of local Kentucky health officers – including Acting Health Officer Norment – met at the Seelbach Hotel to discuss the possibility of lifting the ban, at least in Louisville. Instead, state health authorities not only affirmed the existing closures, but also tightened and extended the restrictions. Effective the next day, the state Board of Health ordered all saloons and soft drink stands to close between 6:30 pm until 6:30 am. Only churches and synagogues had some measure of latitude – the Board permitted churches to open for individual prayer and meditation.20

Louisville’s epidemic continued to abate over the course of the rest of the month. By October 22, the city’s newspapers were happily reporting that influenza’s high mark had been reached on two weeks earlier, and that the number of new cases was on the steady decline.21 On October 30, state and local health officers as well as representatives from the Red Cross and the Louisville Board of Trade met once again at the Seelbach to discuss the lifting of the bans. Norment stated his belief that the city’s epidemic had run its course, and that there would be no danger in allowing public gathering places to reopen. Clergy argued that allowing regular religious services would lift the morale and spirit of residents, and thus stimulate their resistance to influenza. The arguments fell on deaf ears, as once again the state Board of Health voted to continue the closure orders, although this time it provided a possible timeframe for when they might be lifted – one week. The problem was not so much with Louisville as it was with the surrounding Jefferson County, which was still in the midst of a serious epidemic. If Louisville were allowed to reopen, some believed that visitors would flock to the city for amusement, thus bringing influenza with them.22 Until the situation in Jefferson County improved, the bans would remain in place.

As October turned into November, conditions in Louisville continued to improve. Finally, on November 6, the Kentucky Board of Health announced that the closure order and gathering ban would be lifted for the Louisville area effective Sunday, November 10 for churches and Monday, November 11 for all other places. The Board omitted mention of the business hour restrictions on saloons and soda fountains, as these measures were enacted in a separate order. Secretary McCormack stated that the Board would have to take up this issue at its next meeting, although he hinted that the decision might be left up to local health officials. Norment, pleased that the major closure order would soon be removed, vowed to ensure that saloons and soda fountains followed the restricted business hours for the time being.23

Churches reopened on Sunday, November 10, the first time the pews were occupied for regular service in five weeks. To prepare for the complete reopening of the city and to help stave off a return of the epidemic, the Louisville Boards of Health and Public Safety issued a set of regulations to prevent crowding. All stores were to be fully ventilated at all times and kept at a proper temperature. All employees exhibiting symptoms of illness were to be sent home at once, returning to work only when provided with a certificate from their physician. Stores were to employ enough staff to prevent congestion. For pool halls and bowling alleys, owners and managers were to grant admittance to those actually engaged in games. Movie house and theater managers were likewise prohibited from allowing crowds to gather inside their establishments. This did not prevent crowds of eager entertainment seekers from forming long lines as people rushed to purchase tickets for the evening’s shows.24

By Thanksgiving, physicians were reporting a slight but nonetheless noticeable increase in influenza cases. Norment remained optimistic that the worst was over, and that, while Louisville would experience elevated case burdens throughout the winter, residents need not fear a return of the epidemic.25 A little over a week later, attendance at schools in the Crescent Hill neighborhood had dropped by 50% due to influenza. Physicians reported a considerable increase in cases. In fact, a group of concerned physicians petitioned McCormack and the state Board of Health to re-implement the closure order and gathering bans so that the epidemic could be brought under control. The Board refused the request because members hoped that a recently shipped supply of 100,000 doses of influenza serum would soon do the job. In the meantime, the Board asked residents to avoid crowds, cover their coughs and sneezes, and remain in bed if feeling ill.26

On December 12, Health Officer Baker – returned from his medical leave – called a meeting of the Mayor, Norment, and McCormack, as well as representatives of the medical community, churches, schools, fraternal organizations, businesses, and amusement concerns to discuss whether Louisville should implement a second round of closure orders.27 Of particular concern were schoolchildren. Reviewing the latest data, the group agreed that a second school closure order was necessary. The next day, Baker announced that schools would be closed and children under 14 banned from theaters and other public gathering places effective December 14.28 To further safeguard youngsters, the city health department stationed inspectors in stores and motion picture theaters to serve as enforcers.29 Children did not have to wait long before regaining admittance to their favorite places of amusement. Within two weeks the epidemic subsided drastically, leading Baker to reopen Louisville’s schools on December 30. A week later, he announced that children could once again attend movie houses and five-and-ten cent stores.30

Conclusion

Louisville was not quite out of the woods yet, however. In late-February 1919, the health department documented a sudden, third spike in influenza cases that lasted approximately five weeks. The cases were generally much milder this time, however, and thus neither Baker nor the state Board of Health considered issuing a third closure order. It was not until the end of spring that conditions returned to normal.

Between September 26 and November 16, 1918, Louisville physicians reported a total of 6,736 cases of influenza to the health department, of which 577 resulted in death.31 Louisville’s excess death rate for the fall and winter was 406 per 100,000 people, average for its geographic region. Cincinnati, for example, had an excess death rate of 451 per 100,000, and Dayton 410. To the south, Nashville fared much worse, with an excess death rate of 610 per 100,000.

There can be no doubt that Louisville, like nearly every city, was challenged to care for its stricken during this time. The quick and decisive action of city officials and especially the health department, however, greatly mitigated what could have been a much worse epidemic. Under the auspices of the health department, hospital and homecare was organized and coordinated, incorporating the help of the Red Cross, the Visiting Nurses, and other community charities and services. As the tempo of new cases increased, successful calls for volunteers and the creation of a well-staffed temporary emergency hospital augmented the system of care. Many other American cities had to plead for volunteers, both from within and from without. In Louisville, the situation was well enough in hand throughout the epidemic that the city was able to furnish nurses to hard stricken communities in the hardscrabble sections of eastern Kentucky.32

Notes

1 “Influenza Rampant,” Louisville Times, 24 Sept. 1918, 8; “Flu Cases Increase,” Louisville Times, 25 Sept. 1918, 1; “Steps Taken to Prevent Flu Spread,” Louisville Times, 28 Sept. 1918, 1.

2 “Sweeping Order Issued to Men at Local Camp,” Louisville Times, 27 Sept. 1918, 1.

3 “Closes shows to soldiers,” The Courier-Journal 3 Oct. 1918 1.

4 “City and U.S. Take Steps to Check Spread of Flu,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 27 Sept. 1918, 10.

5 “Join Hands in Fight on Flu,” Louisville Times, 28 Sept. 1918, 1.

6 Annual Report of the Board of Health, City of Louisville, KY, for the fiscal year ended August 31, 1919. [Louisville: 1919], 38-39.

7 “Spanish Flu Is Discovered Here; Three Infected,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 20 Sept. 1918, 1.

8 “Women Asked to Loan Cars to ‘Flu’ Workers,” Louisville Times, 3 Oct. 1918, 12; Louisville, Ky. Board of Health. Annual Report of the Board of Health, City of Louisville, KY, for the fiscal year ended August 31, 1919 (Louisville, 1919), 53.

9 Annual Report of the Board of Health, City of Louisville, KY, for the fiscal year ended August 31, 1919 (Louisville, 1919), 53.

10 Helen B. Lupton, “Influenza in Louisville, Ky.” Public Health Nurse vol. 9, no. 1 (1919): 48.

11 “Schools to Close while Flu Rages,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 7 Oct. 1918, 1.

12 “Closing Order Hits Churches,” The Courier-Journal, 8 Oct. 1918, 4.

13 “No Rest for City Health Officials,” Louisville Times, 12 Oct. 1918, 3.

14 “State board to enlarge rules for quarantine,” Louisville Times, 9 Oct. 1918, 1, 11.

15 Helen B. Lupton, “Influenza in Louisville, Ky.” Public Health Nurse vol.9, no. 1 (1919): 48; “No Rest for City Health Officials,” Louisville Times, 12 Oct. 1918, 3.

16 “No Rest for City Health Officials,” Louisville Times, 12 Oct. 1918, 3.

17 “Will Help Educate Public as to Flu,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 20 Oct. 1918, 8.

18 “Health Edict Banishes Santa,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 9 Nov. 1918, 1, 2.

19 Louisville, Ky. Board of Health. Annual report of the Board of Health, City of Louisville, KY, for the fiscal year ended August 31, 1919 (Louisville, 1919), 53.

20 “Ban Tightened to Check ‘Flu,’” Louisville Courier-Journal, 19 Oct. 1918, 1,2.

21 “City Gains in Fight on Flu,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 22 Oct. 1918, 1.

22 “Flu Lid Still Clamped Down,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 31 Oct. 1918, 1.

23 “’Flu’ Quarantine is Modified Here; Effective Sunday,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 7 Nov. 1918, 1; “Flu’ Ban Lifted, Subject to Rule of Local Board,” Louisville Times, 7 Nov. 1918, 7.

24 “’Flu’ Lid is Off; Churches Open,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 10 Nov. 1918, 1; “Schools Open this Morning,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 11 Nov. 1918, 2.

25 “Flu Showing Increase; Norment is Optimistic,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 26 Nov. 1918, 1; “Flu Cases Take Spurt,” Louisville Times, 30 Nov. 1918, 12.

26 “Seventy Cases Now,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 3 Dec. 1918, 9; “Hold Quarantine to See Results Serum May Give,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 7 Dec. 1918, 8.

27 “Flu Ban May Be Clamped Down,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 13 Dec. 1918, 1, 2.

28 “Tots Barred from Crowds,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 14 Dec. 1918, 1,2.

29 “Influenza on Wane; May Lift Ban Jan. 1,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 27 Dec. 1918, 5.

30 “Modified Ban on Influenza off Dec. 30,” Louisville Times, 28 Dec. 1918, 1; “Influenza Ban is Entirely Lifted,” Louisville Times, 6 Jan. 1919, 1.

31 Annual report of the Board of Health, City of Louisville, KY, for the fiscal year ended August 31, 1919 (Louisville, 1919), 38.

32 “East Kentucky in Dire Straits,” Louisville Courier-Journal, 2 Nov. 1918, 1.

Click on image for gallery.

The Seelbach Hotel, circa 1905. During the deadly influenza epidemic, city and state health officials frequently met at the stately Seelbach to plan Louisville’s public health response. It was also the site of Daisy’s wedding in the famous F. Scott Fitzgerald novel The Great Gatsby.

Click on image for gallery.

The Seelbach Hotel, circa 1905. During the deadly influenza epidemic, city and state health officials frequently met at the stately Seelbach to plan Louisville’s public health response. It was also the site of Daisy’s wedding in the famous F. Scott Fitzgerald novel The Great Gatsby.