Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

Surpassed in influenza deaths in major cities in the United States only by Pittsburgh, Philadelphia’s epidemic hit the City of Brotherly Love like a proverbial freight train. The first handful of cases in the city appeared in late-August but garnered little attention from either residents or Philadelphia’s Director of Public Health and Charities, Dr. Wilmer Krusen. Krusen was mostly concerned with helping medical staff at the Naval Hospital handle the growing epidemic in the Fourth Naval District. As a result, on September 18 he reserved 150 beds at the Municipal Hospital for Contagious Diseases for use by the Navy. Despite the city’s first influenza death – an 89 year old banker - Krusen offered civilian residents the soothing statement that they had nothing to fear so long as influenza cases were strictly isolated.1

Krusen was terribly wrong. The next day, reports spread that the Naval Hospital received 400 new cases from the Naval Yard in just the past three days. Civilian cases were increasing as well, and all of the city’s larger hospitals were caring for both resident and military patients. Still, Krusen insisted that there would be few deaths from the epidemic, and that isolation of the sick would quickly bring the outbreak under control.

Philadelphia’s soon-to-be-beleaguered public health officer may have been a Pollyanna, but he was not a liar. Without the means to understand that the growing influenza epidemic was caused by a novel strain of a virus – a microbe that would not be isolated for another fifteen years – physicians and public health officers had no understanding that they were on the brink of something far more terrible than the common seasonal flu. And something far more terrible Philadelphia was about to experience.

For the next week, the city’s epidemic appeared to have stalled. Under the headline, “Epidemic Slows Up, Deaths Increase,” the Philadelphia Inquirer informed readers that the commander of the Fourth Naval Reserve District, the epicenter of the outbreak, was confident that the crest had been passed. Still, conditions in Philadelphia and across Pennsylvania concerned officials enough that the city Board of Health made influenza a mandatory reportable disease effective September 21 so that they could more accurately track the epidemic.2 These conditions did not concern Krusen and others enough to halt the Fourth Liberty Loan Parade, however. Full of patriotism and believing that the epidemic just starting to rage across many Eastern cities in the United States was overblown, civic leaders and some 200,000 Philadelphians amassed along Broad Street on September 28 to cheer on the long parade of marchers, floats, and Liberty Loan salesmen. Philly, they would show the nation, would not shirk its patriotic duty. The decision, however, would turn out to be a fateful one.

Within a few days of the parade, Philadelphia was rocked by a massive spike in the number of influenza cases. Hospital beds quickly filled, and the city’s physicians and nurses were overwhelmed by the surge. Still, city officials hesitated to take decisive action. On September 30, a conference was held between representatives of the city’s Department of Public Health and Charities, the State Department of Health and Emergency Aid Committee, the Chief of the City Bureau of Health Dr. A. A. Cairns, and Krusen. The only decision taken was that a circular be sent to all state health agencies detailing methods of prevention and treatment of influenza.3 The next day, Philadelphia Mayor Thomas Smith placed a $100,000 emergency fund at the disposal of Krusen.4 He would soon need every dollar of it to fight his city’s epidemic.

At noon on October 3, State Health Commissioner Dr. Franklin B. Royer, witnessing the growing epidemic across Pennsylvania, issued a mandatory state-wide closure order effective at midnight for all places of public amusement, including theaters, poolrooms, dance halls, and salons. Liberty Loan meetings were ordered suspended, and funerals kept private when the cause of death was known to be influenza. Saloons, hotel and club bars, and cafés were also closed. The closure of schools and churches was left up to the discretion of local authorities; with a reported 4,000 pupils in the city sick, however, the Philadelphia Board of Health simultaneously ordered all private, parochial, and public schools closed, along with all churches and other places of worship.5

Reactions to the closure orders were mixed. The Philadelphia Inquirer believed that Royer’s and Krusen’s orders went too far, and that the sudden shut-down of schools, churches, and places of public amusement only served to promote unreasonable fear and panic. Editors instead advised residents maintain a normal lifestyle and their health by getting enough sleep, eating well, and exercising. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, on the other hand, believed that the new closure orders were completely necessary, stating that crowds spread influenza and that readers should remain patient as the epidemic could take several more months to run its full course.6 The coming weeks would prove the astute editors of the Evening Bulletin correct.

By October 5, just as the new closure orders were going into full effect, Philadelphia reported nearly 1,500 new influenza cases. Many employees of the health department were reported among the sick, and manufacturing executives of the city’s many war industries plants reported that ten to twenty percent of their workforces had been stricken by influenza.7 Only two days later, the number of cases grew to 5,561. North Philly alone, the industrial hub of the city and the workingman’s section, had over 3,000 influenza cases. The surge in new influenza cases quickly overwhelmed hospitals and medical staff. Krusen called on senior medical students from the University of Pennsylvania, Jefferson College, and Hahnemann College to assist overworked hospital physicians, and over 300 volunteered for service. Civic organizations requested that all women with nursing training lend their aid as well. Meanwhile, the clubhouse of the Philopatrian Literary Institute, the old Medico-Chirurgical Hospital, the Twenty-sixth Ward Republican Club at Broad and Tasker Streets, and the Divinity School at Fiftieth and Woodland Ave. were quickly converted to makeshift emergency hospitals.8

Despite the growing caseload, however, Krusen declared that “Epidemic influenza in Philadelphia has reached its crest.”9 The Inquirer felt vindicated in its earlier editorial, and now claimed that ninety-nine percent of those who remained calm would be spared, while only the fearful would fall victim to the epidemic. The rights and responsibilities for avoiding infection, the editors wrote, rested firmly with the individual, who must practice good hygiene and common sense. A clean mind and a clean life were necessary; sweeping closure orders were not. To bolster these claims, the editors cited several city physicians who believed much the same. Dr. John W. Croskey, president of the West Philadelphia Medical Association, began and anti-scare campaign, stating that “the public should be educated to the fact that the disease is not as deadly as many believe it to be.” He estimated the case fatality rate to be less than 0.5 percent. Another prominent Philadelphia physician proclaimed that the editorial, if placed in the hands of every resident in the city, would do more to halt the spread of influenza than any of the closure orders issued by state and local health officials.10

The editors of the Inquirer were incorrect, but Krusen may not have been when he claimed that Philadelphia’s epidemic curve had reached its peak. By the start of the second week of October, the number of new influenza cases being reported in the city began to stabilize and then slowly decline. The situation was still dire, however, as the epidemic was causing several thousand new cases per day and as even the city’s overflow emergency hospitals were quickly overwhelmed. Several churches donated their buildings – including all of the Catholic Archdiocese’s parochial schools - to the effort should city officials need them, and a steady stream of volunteers lent their services to the Emergency Aid Headquarters. Countless residents across the city jumped into action to care for non-critically ill neighbors, relieving some of the strain on physicians and nurses, or to donate food and clothing to assist the poor whose plight was made worse by the epidemic. As the death toll continued to rise, Krusen and city Coroner William Knight pressed asked municipal workers to volunteer as gravediggers to inter the rising number of bodies that had fallen to the epidemic. Police officers, whose ranks were drastically thinned by the 400 patrolmen out sick with influenza, assisted coroners whenever possible, and some sixteen police stations were converted into emergency health departments. Embalmers were in high demand and short supply. The death toll grew so great, so quickly, that the Department of Health and the City Coroner temporarily suspended the ordinance mandating that death certificates be issued before burial. On one day alone – October 15 – ten trucks carried bodies from the city morgue to Philadelphia’s potter’s field at Luzerne Street and Whitaker Avenue in North Philadelphia.11 As in nearly every American community, everyday life was turned completely upside-down by the epidemic.

By the end of October, it appeared as if the worst had passed. On October 20, over 1,300 new cases and 606 deaths were reported; ten days later, only 125 new cases and 317 deaths were logged. With the worst behind them, city leaders pressed Pennsylvania Acting Health Commissioner Royer to lift the closure orders, effective Monday, October 28. Royer, however, felt such a move would be premature. After reviewing Philadelphia’s case data, however, Royer relented, and granted Royer and the Board of Health the authority to re-open the city. On Wednesday, October 30, theaters, movie houses, saloons, and other places of public amusement once again opened their doors for business. School Superintendent Dr. John Garber announced that all city public schools would re-open as well. Most private schools followed suit. Catholic parochial schools elected to wait until November 4 to welcome students back to their classrooms, as many teaching sisters were still volunteering in hospitals and homes. Clergy could once again hold services for their congregants. After a month of social and economic dislocation, Philadelphia was slowly returning to life as it was before the epidemic. And it was none too soon for many business owners. The closure orders were estimated to have cost theater, movie house, and hotel owners a whopping $2,000,000. The city’s transit company was said to have lost $250,000 as a result of the drastic reduction in ridership. Saloon owners reported losing $350,000 in business, although at least some of that loss was quickly remade in the day after the closure orders were lifted; on October 31, police arrested 53 people for drunkenness in West Philly alone, the largest number of such arrests ever made in that section of town.12

Krusen warned the public that sporadic influenza cases would continue throughout the winter, and called on those who fell ill to isolate themselves. He also advised residents to get plenty of fresh air, sunshine, and rest as they fell back into their pre-epidemic routines. As the number of new cases declined and as patients began to recover from their bouts with the illness, Philadelphia’s 32 emergency hospitals were slowly dismantled. Throughout the rest of November, nurses and other volunteers continued to make house calls to check on patients as they convalesced in their homes. State authorities in Harrisburg, recognizing the significant problem across Pennsylvania of caring for the estimated 50,000 children orphaned in the state by the terrible epidemic, directed local school districts to create committees to identify and plan for the care of these children. In Philadelphia, schools were assisted in this work by the Red Cross, the Committee on National Defense, and the State Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis.13 By mid-December, the number of new influenza cases per day in the city slowed to a trickle, and life in Philadelphia returned – as much as possible – to what counted for normal after such a devastating blow.

As in most other American communities, January brought an increase in influenza. Krusen and his colleagues worked to identify and place these cases in a 10-day isolation in order to prevent a more widespread outbreak. With the disease having run so rampant in the fall, however, the cases and deaths were fortunately far fewer than Philadelphia had seen just a few months earlier. So many in the city had experienced a bout with influenza and had therefore developed immunity to the dreadful epidemic strain that Philadelphia was spared another sharp peak of cases and deaths.

Conclusion

With one hundred years of hindsight, today Philadelphia’s battle with the 1918 influenza epidemic is often seen as an example of what not to do. In particular, the decision to allow the Fourth Liberty Loan Parade to take place right as the city’s epidemic was about to accelerate is held up as an object lesson in poor public health decision-making. Krusen, in particular, has become a convenient foil for more far-sighted health officers such as Dr. Max Starkloff of St. Louis. To be sure, that fateful parade decision greatly aided the rapid and overwhelming spread of influenza throughout the city in the days after September 28, 1918. The United States was involved in a war, however, and patriotism and the government-stoked drive to “Beat back Hun with Liberty Bonds” was strong. Furthermore, by law, Krusen lacked the authority to cancel the parade; that authority ultimately rested with Philadelphia Mayor Thomas Smith. Most important, neither Krusen nor any other public official could have reasonably realized in late-September 1918 that Philadelphia’s epidemic curve was about to rapidly accelerate. On the eve of the fated parade, there were only a few dozen civilian influenza in the city, and the epidemic seemed mostly confined to the Philadelphia Navy Yard. More than a lack of public health foresight, Philadelphia was the victim of incredibly poor timing and bad luck. In the end, the city experienced a excess death rate of 748 deaths per 100,000 population, one of the worst in the nation.

Philadelphia’s epidemic outcome was largely shaped by two factors: its location as an East Coast city, and its insistence on holding the fateful Fourth Liberty Loan Parade at the exact moment that the influenza epidemic was growing.

Notes

1“Spanish Influenza Causes Death Here,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 9 Sept. 1918, p.1.

2“Spanish Influenza Epidemic Waning,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 23 Sept. 1918, p.22.

3“Epidemic Slows Up, Deaths Increase,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 Oct. 1918, p.5.

4“City Gives $100,000 Fund to Flight ‘Flu;’ Epidemic Spreads,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 2 Oct. 1918, p.1.

5“Theatres, Saloons in Penna. Closed to Halt Influenza,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 Oct. 1918, p. 1; “City to Be ‘Dry’ Tonight; Courts Close for ‘Flu,’” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 4 Oct. 1918, p.1.

6“Spanish Influenza and the Fear of It,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 Oct. 1918, p.11; “The Influenza Edicts,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 5 Oct. 1918, p.12.

7“Influenza Leaps as 1,480 New Cases are Listed Today,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 5 Oct. 1918, p.1.

8“Holds Influenza Is at Its Crest,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 Oct. 1918, p.10.

9Ibid.

10“Stop the Senseless Influenza Panic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 Oct. 1918, p.12.

11“Scientific Nursing Halting Epidemic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 Oct. 1918 p.22; “2,990 New Epidemic Cases; 1,299 deaths,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 15 Oct. 1918, p.1.

12“Ban Raised Here as Epidemic Ends,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 31 Oct. 1918, p.8; “Influenza No Longer Has Official Standing,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 Nov. 1918, p.12.

13“Red Cross Women Heroic in Epidemic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 Nov. 1918, p.5; “State to Care for Influenza Victims,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 Nov. 1918, p.24; “50,000 Orphaned by Epidemic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 Dec. 1918, p.19.

Click on image for gallery.

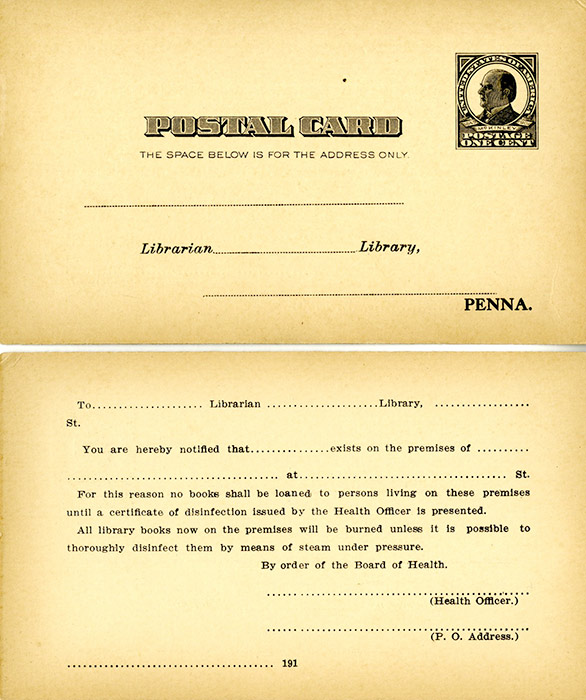

A postcard used by local Pennsylvania health officers to notify librarians that books should not be loaned to patrons identified as having a contagious disease, and that those books already borrowed will be disinfected or destroyed. In many communities, this was done for books borrowed by influenza households as well.

Click on image for gallery.

A postcard used by local Pennsylvania health officers to notify librarians that books should not be loaned to patrons identified as having a contagious disease, and that those books already borrowed will be disinfected or destroyed. In many communities, this was done for books borrowed by influenza households as well.

Click on image for gallery.

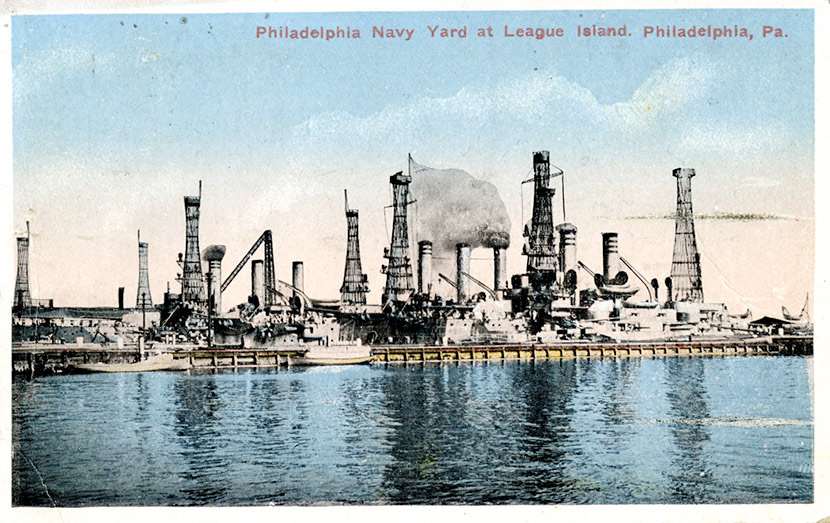

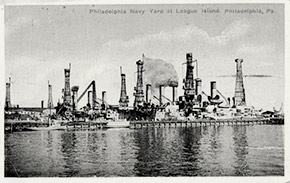

The Philadelphia Naval Yard at League Island, at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. It was the first naval shipyard in the United States. As was the case with nearly every American military installation, the naval yard was hit early and hard by influenza.

Click on image for gallery.

The Philadelphia Naval Yard at League Island, at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. It was the first naval shipyard in the United States. As was the case with nearly every American military installation, the naval yard was hit early and hard by influenza.