Produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library

Influenza Encyclopedia

The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919:

A Digital Encyclopedia

Rochester, New York

50 U.S. Cities & Their Stories

On September 27, 1918, New York Health Commissioner Dr. Herman Biggs issued a public warning to residents across the state on the dangers of epidemic influenza. He noted that the disease itself was seldom fatal, but that the complicated pneumonia that frequently developed from it was quite dangerous. Strict quarantine was not practical, Biggs told the public, due to the highly contagious nature of influenza. Instead, those who developed symptoms should rest at home in bed until they were fully recovered. He advised the healthy to avoid poorly ventilated or crowded places.1

As of yet, only two cases of influenza had been reported to the Rochester Board of Health, and neither was confirmed. Influenza was not yet a reportable disease in Rochester, and officials had no way of knowing the true extent of the epidemic. The following day, September 28, four officially diagnosed cases of influenza were reported in the city, one of them a soldier recently arrived from Camp Dix, New Jersey.2 Rochester’s epidemic had begun.

A week later, Acting Health Officer Dr. Joseph Roby estimated nearly 1,000 cases in Rochester. The official number was still unknown, as the disease was not yet reportable. Regardless, officials realized that the city was either in the midst of or about to experience a severe epidemic and began to prepare. Rochester General Hospital set up a separate influenza ward. Education officials discussed the possibility of closing schools. The Army Aerial Photography School cancelled all leave and barred visitors from entering.3

The planning stage did not last long. On October 9, Commissioner of Public Safety Andrew Hamilton announced that all public, private, and parochial schools would close at noon, after students received instructions on influenza prevention and care. At 11:30 pm that evening, all theaters, movie houses, skating rinks, bowling alleys, and other places were to close. Any scheduled performances for that evening that extended beyond that deadline would be permitted to finish. Gymnasium classes and the pool at the Rochester Y.M.C.A. were suspended.4 The Chamber of Commerce, in conference with city officials and employers, asked retail shops to stagger business hours and the Eastman Kodak Camera Company as well as other large industries to stagger their shifts to prevent crowding on trolley cars.5 The next day, Commissioner Hamilton ruled that bowling alleys could remain open, but that no spectators would be allowed in the halls.6 Two days later, Hamilton extended the closure order to churches, soda fountains and ice cream parlors, saloons and hotel bars, and lodge and civic association meetings.7

Rochester’s epidemic grew in intensity over the course of the next several weeks. Physicians, whose ranks were thinned by nearly a quarter due to wartime service, were overwhelmed with cases. Nurses worked round-the-clock. By early-October it became clear that the general hospitals soon would be overrun with patients. With the help of the Red Cross and local institutions, Rochester opened and equipped several additional emergency hospitals: Infants’ Summer Hospital, for use by stricken soldiers; the local Y.M.C.A., used for women and children; the Baden Street Emergency Hospital for men, the Housekeeping Center on Lewis Street; and, for nine days only, Gannett House, the parish house of the First Unitarian Church.8 Together, these emergency hospitals helped relieve much of the strain placed on Rochester’s general hospitals as they tried to deal with the massive influx of influenza and pneumonia patients.

By the end of October, over 10,000 cases of influenza had been reported to the Bureau of Health, and nearly 450 patients had died as a result.9 According to Health Officer Roby, however, most of the newer cases were milder. In addition, the number of influenza patients in the city’s hospitals had decreased. Residents were hopeful that the restrictions therefore would be removed soon. Theater workers, in particular, wanted them removed, as they were among the most affected by the closures. At least four hundred people connected with Rochester’s theaters were temporarily out of work, and, because the epidemic was considered an “act of God,” they were not receiving paychecks.10 Commissioner Hamilton, while sensitive to the plight of city workers, was not convinced that the slightly better epidemic news warranted lifting the closure order. After an additional week of decreasing case reports, however, Roby was. At 7:00 pm on Tuesday, November 5–Election Day–the closure order was removed.11

Public schools opened the following day, giving officials time to prepare the buildings and staff. Many teachers had to be recalled from volunteer service, and a number of them were ill with influenza themselves. Rochester’s Catholic schools remained closed an additional week in order to allow the sisters who had been caring for the ill to rest before resuming their teaching duties. As in other communities that had closed schools, Rochester was in a bit of a quandary as to how best to make up the lost classroom days. The School Superintendent believed that the only way to proceed was to observe only actual holidays and not the usual associated breaks. Thus, children would be required to attend school the day after Thanksgiving as well as the day after Christmas.12

Rochester slowly recovered from its epidemic. The city experienced a slight second peak in early- to mid-December, but the number of new cases never rose high enough for officials to consider a second closure order. Residents were pleased by the decision, especially those who once again would have been thrown out of work. The epidemic had been particularly costly to them. For the city, the epidemic reduced Rochester’s coffers by an estimated $20,000, although some of that money went to more permanent equipment such as beds that could be used in future health crises.13

The death toll was even more devastating. All told, Rochester experienced nearly 30,000 cases of influenza. Of these cases over 1,000 resulted in death. Yet despite these high numbers, Rochester’s epidemic was much less severe than that of many other American cities, including ones in New York. Albany, for example, had an excess death rate of 553 per 100,000. Buffalo’s was 530 and Syracuse’s 541. Rochester, by comparison, had an excess death rate of 360 per 100,000, nearly identical to that of St. Louis, touted as one of the best examples of epidemic handling in the nation. Like St. Louis, Rochester officials reacted quickly to the growing number of influenza cases in the city, enacting social distancing measures within a matter of days after realizing that the epidemic had begun.

Notes

1 “No Spanish Influenza Reported Here as Yet,” Rochester Times-Union, 27 Sept. 1918, 21.

2 “Spanish Influenza Here, Four Cases Are Reported,” Rochester Times-Union, 28 Sept. 1918, 9; Annual Report of the Health Bureau, City of Rochester, NY, 1918 (Rochester, NY: 1919), 318.

3 “Influenza Here Increases, But Not Alarmingly,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 7 Oct. 1918, 14; “Will Likely Close Schools to Prevent Influenza Spread,” Rochester Times-Union, 8 Oct. 1918, 8.

4 “Influenza Closes the Schools and All Amusement Places,” Rochester Times-Union, 9 Oct. 1918, 9.

5 “To Change Workers’ Hours as Influenza Preventative,” Rochester Times-Union, 9 Oct. 1918, 9.

6 “Bowling Alleys Not Ordered to Close,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 10 Oct. 1918, 23.

7 “Sweeping Closing Order to Prevent Further Spread of Spanish Influenza,” Rochester Times-Union, 12 Oct. 1918, 8.

8 Annual Report of the Health Bureau, City of Rochester, NY, 1918 (Rochester, NY: 1919), 321.

9 “Reported Influenza Cases Now Number over 10,000,” Rochester Times-Union, 28 Oct. 1918, 8.

10 “Theatrical People Hit by Epidemic,” Rochester Times-Union, 19 Oct. 1918, 8.

11 “Additional Evidence Nears End,” Rochester Times-Union, 5 Nov. 1918, 8.

12 “No Plans for Making up Time in the Schools,” Rochester Times-Union, 5 Nov. 1918, 8.

13 “No Death from Either Pneumonia or Influenza,” Rochester Times-Union, 7 Jan. 1919, 8.

Click on image for gallery.

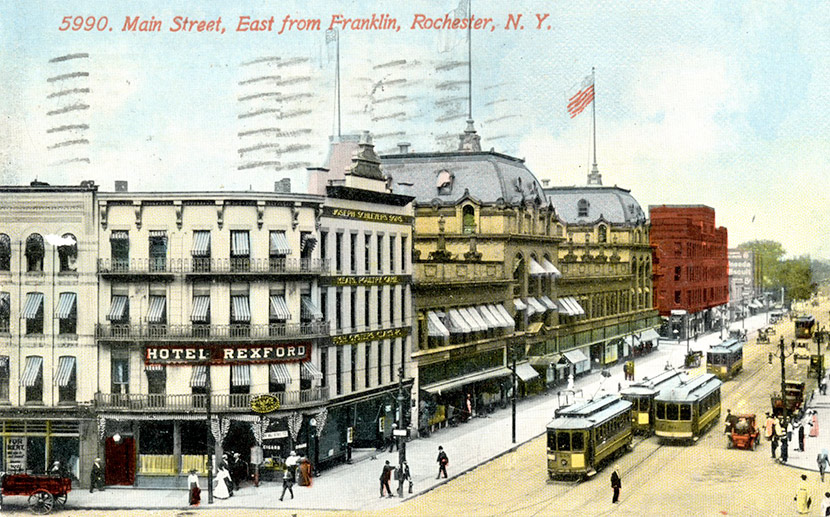

Main Street looking East from Franklin ca. 1912. The next year, the Hotel Rexford (8 Franklin Street) became the Hotel Berkeley. Otherwise, the block would have looked much the same in 1918. In 1955, the Monroe County Savings Bank was built on the site. Today, the Salvation Army is located in the building.

Click on image for gallery.

Main Street looking East from Franklin ca. 1912. The next year, the Hotel Rexford (8 Franklin Street) became the Hotel Berkeley. Otherwise, the block would have looked much the same in 1918. In 1955, the Monroe County Savings Bank was built on the site. Today, the Salvation Army is located in the building.

Click on image for gallery.

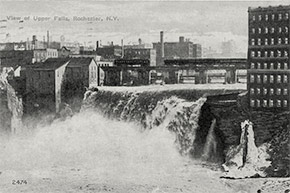

A view of Upper Falls (High Falls) of the Genesee River in downtown Rochester. The falls was the source of Rochester’s flourmills and other industries in the 19th and 20th centuries. This particular postcard was mailed on November 13, 1918, during the city’s influenza epidemic.

Click on image for gallery.

A view of Upper Falls (High Falls) of the Genesee River in downtown Rochester. The falls was the source of Rochester’s flourmills and other industries in the 19th and 20th centuries. This particular postcard was mailed on November 13, 1918, during the city’s influenza epidemic.